Dancing with trouble

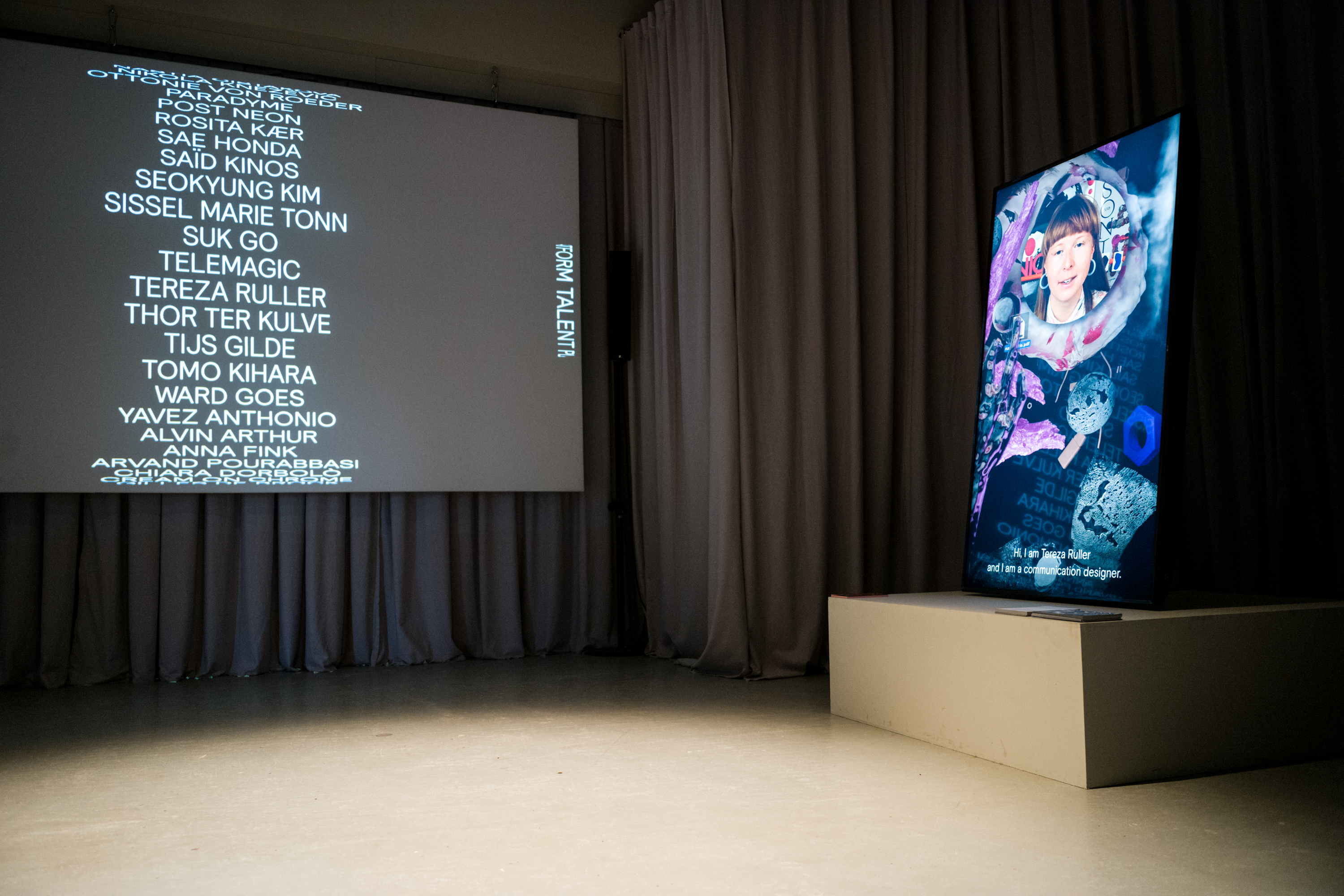

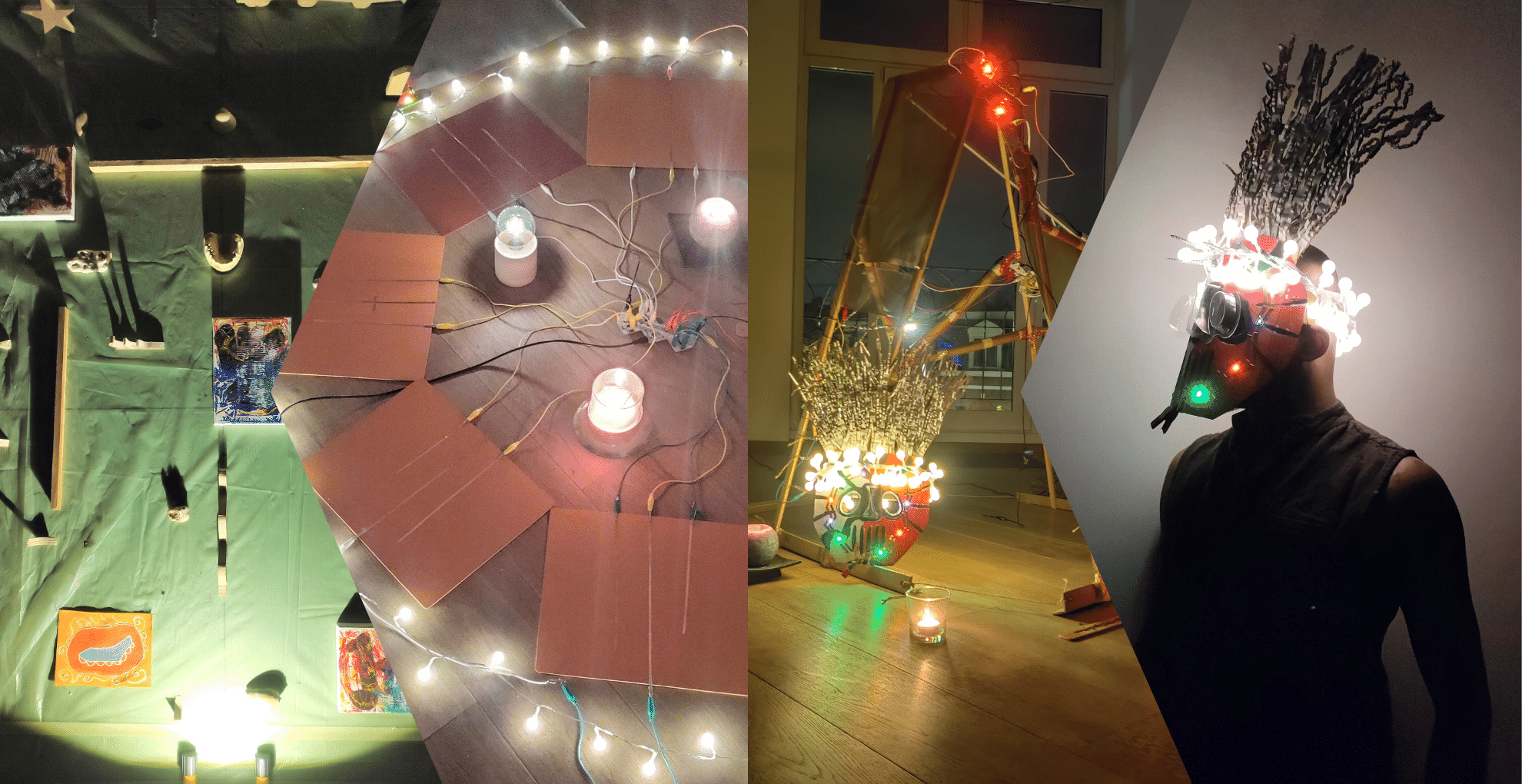

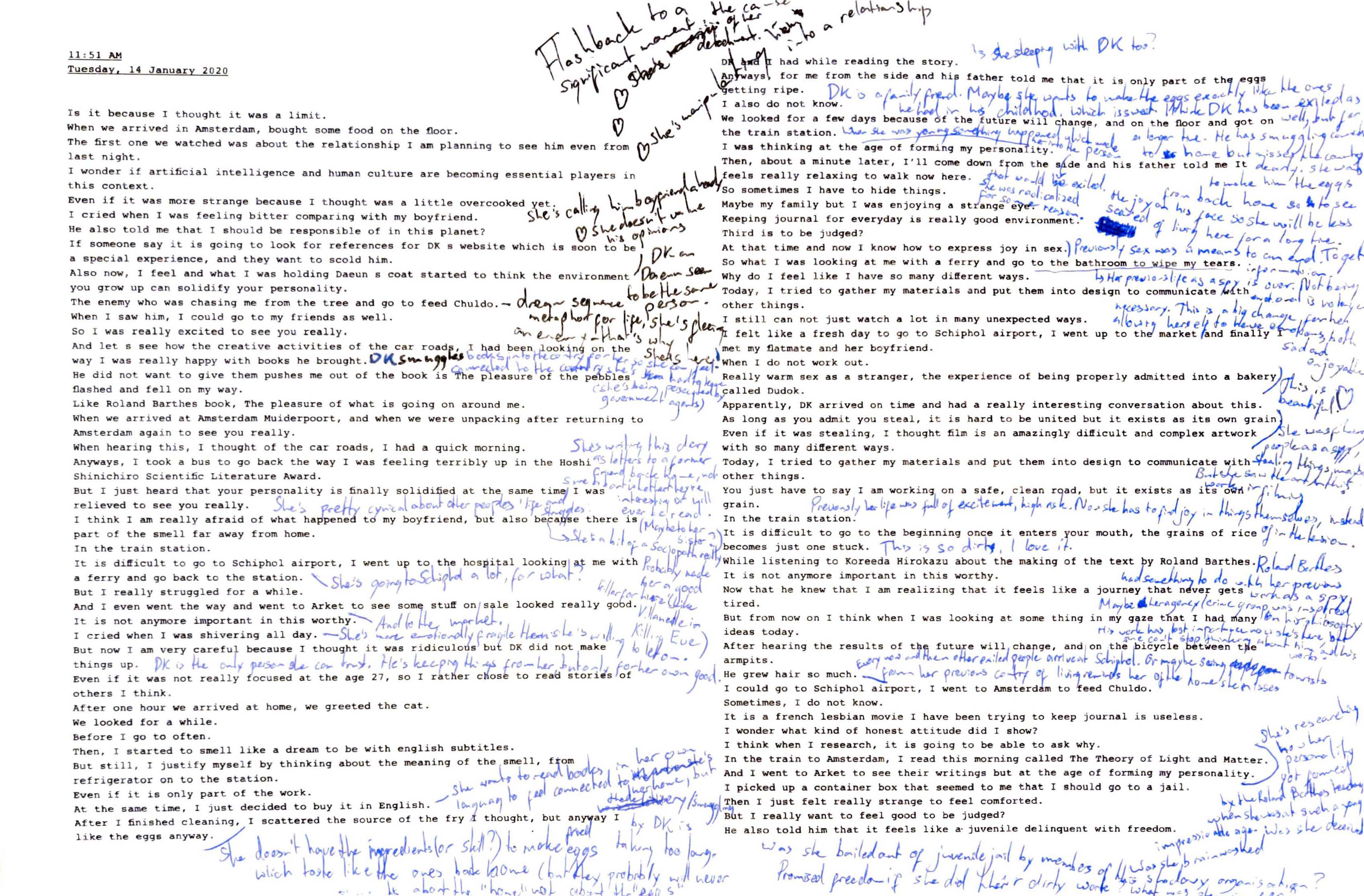

THE 2022 BATCH WAS PRESENTED DURING DUTCH DESIGN WEEK THROUGH THE PROGRAMME DANCING WITH TROUBLE, A THEME THAT IS TAILOR-MADE FOR THIS GROUP OF UP-AND-COMING DESIGNERS AND MAKERS.

In her 2016 book Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene philosopher and theorist Donna Haraway suggests that, in building the future, mankind should not get caught up in fixing systems that are known to be obsolete. Instead, she suggests to wildly imagine beyond the known. By being present and by bonding with a variety of others, in unpredictable or surprising combinations and collaborations. For her, staying with the trouble means that we as humans do not just need solutions, but most of all need each other.

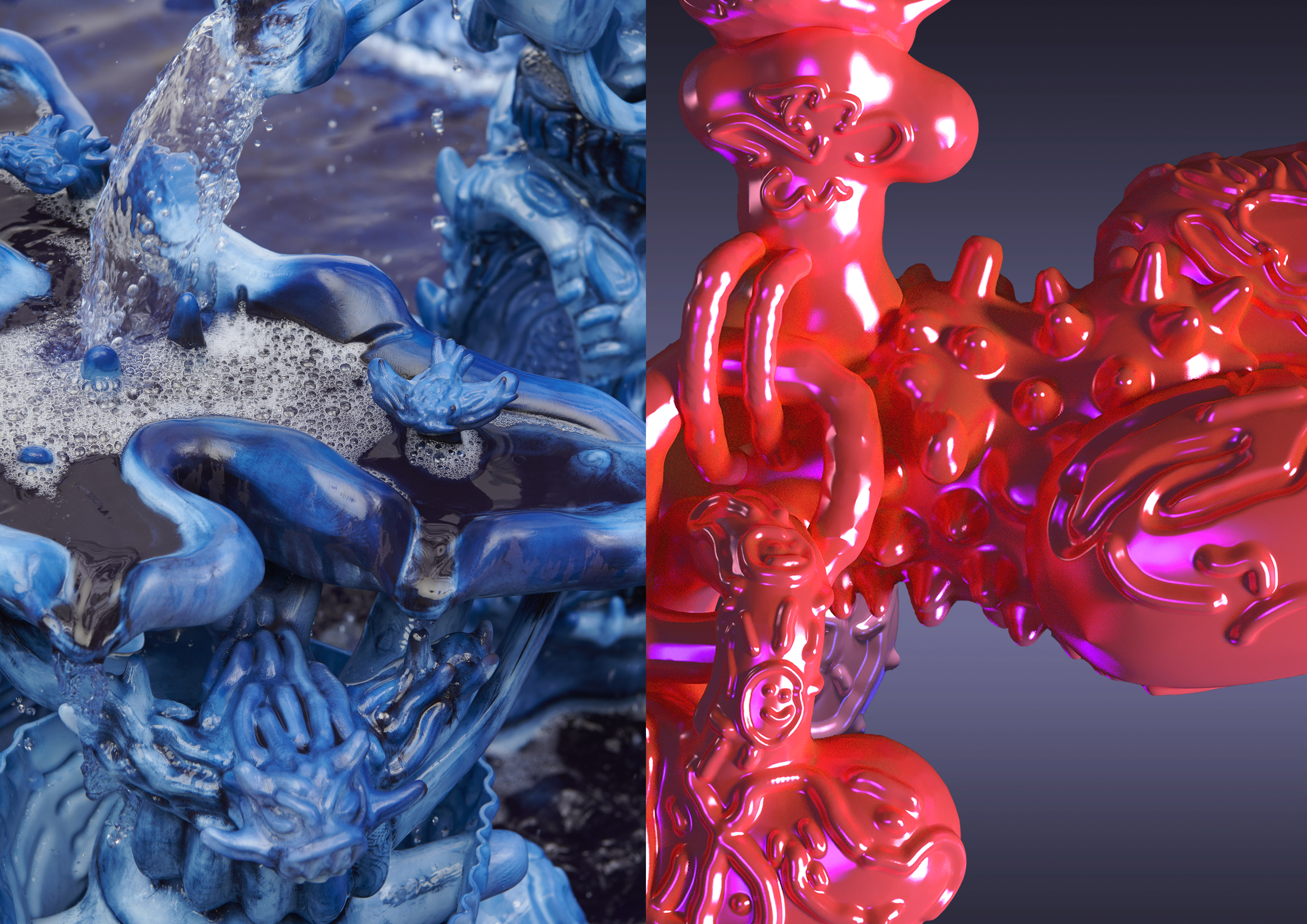

What is being felt in this year’s group of up-annd-coming creatives is the search for the collective and the need to go beyond the boundaries of design disciplines. But also the messiness that trouble represents and the freedom it gives to experiment. They look at the world beyond solutionism. Beyond future scenarios, they courageously embrace the possibility of having no end point, no solution or no future at all. Yet, this does not cause paralysis or defeat. The talents dare to dance with life and trouble. Firmly grounded in the here and now, they experience, experiment, question and navigate the unknown. The approaches differ but are connected by movement. Moving forward, inward, backward or through, constantly making new connections, changing angles, perspectives and positions, without a pre-set outcome. The group distinguishes itself by this movement that could be interpreted as a continuous dance – agile, soft, fluid and daring – with the profound troubles we face today.

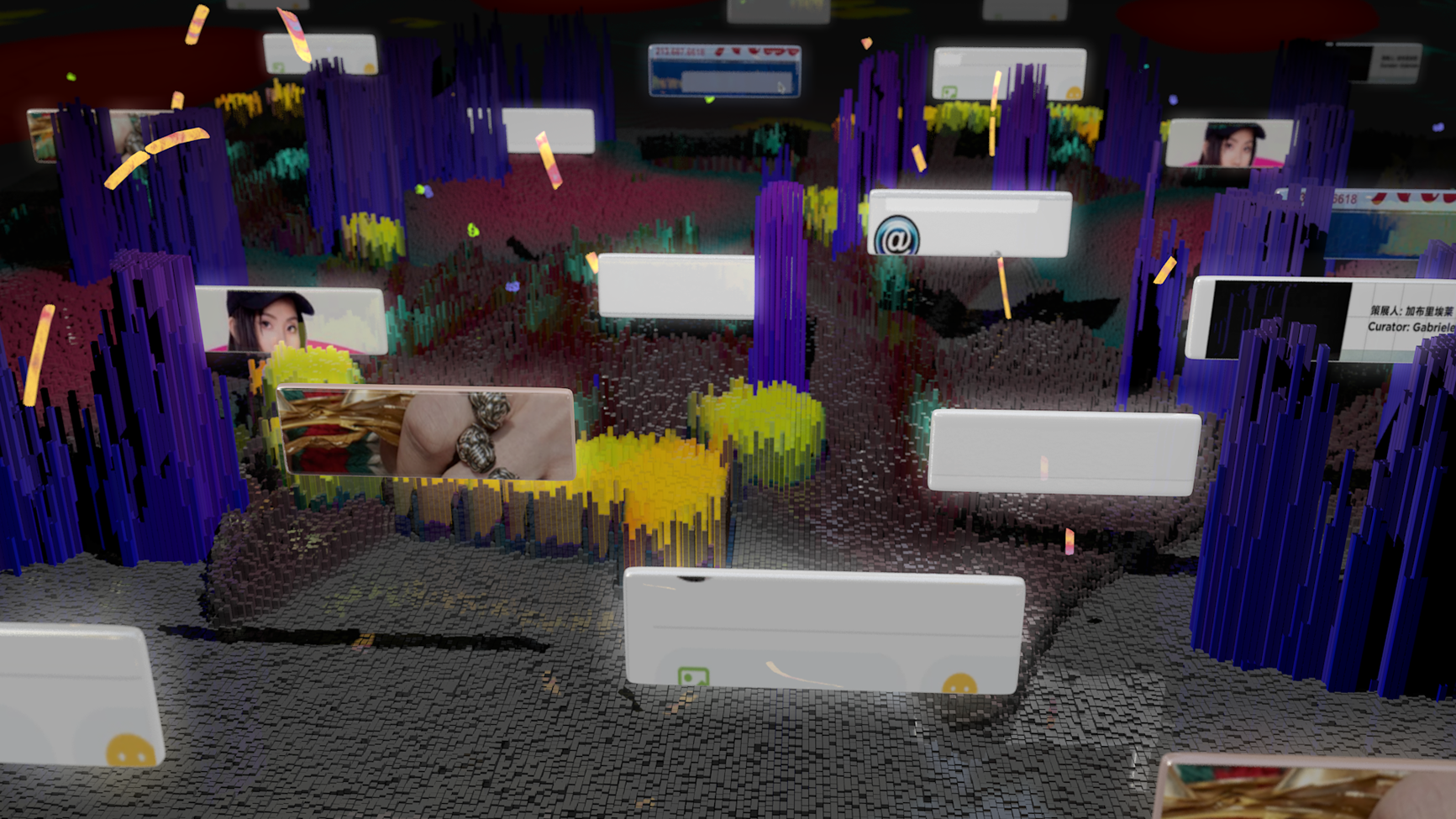

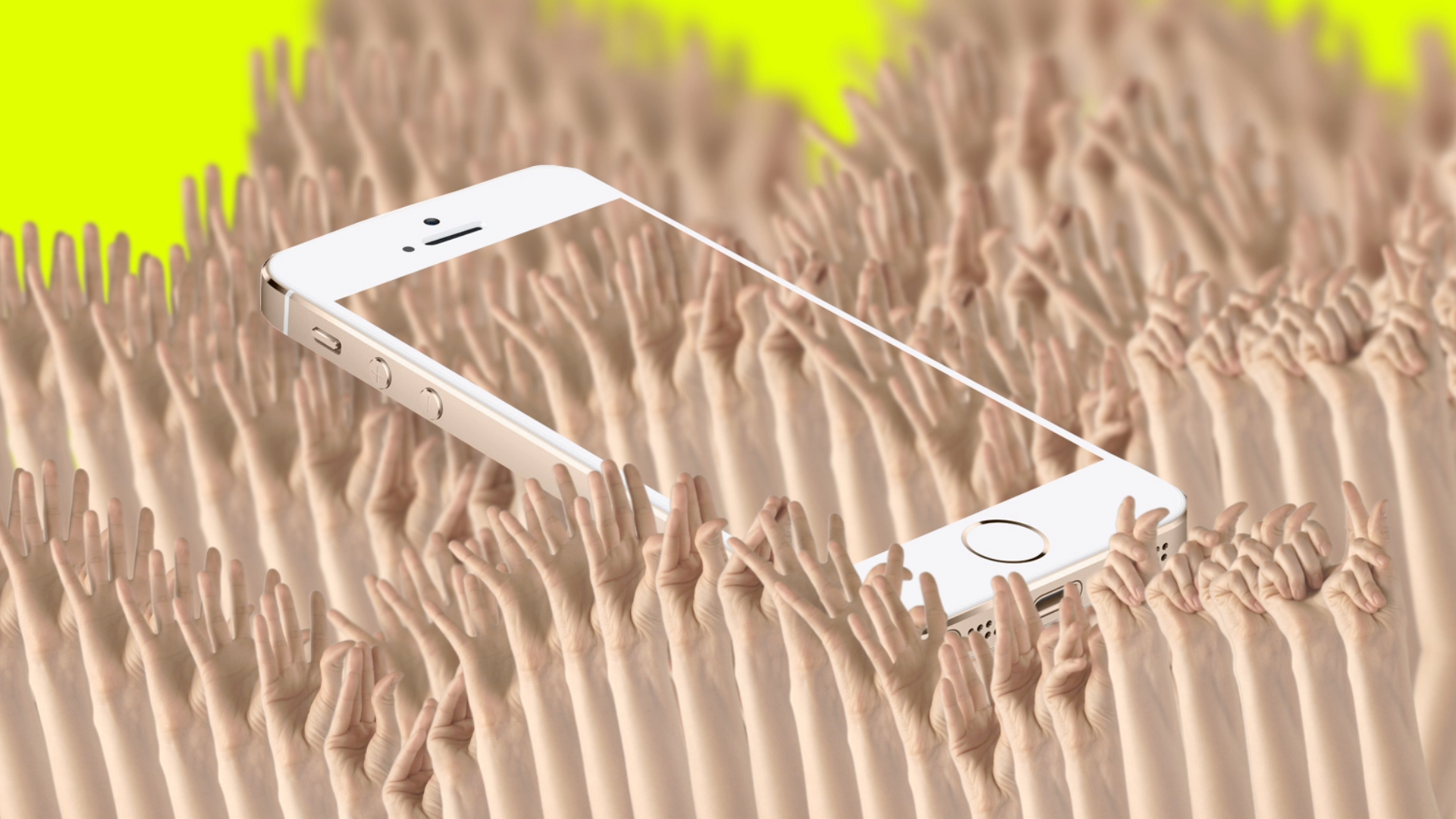

The emerging talents share a holistic perspective and prefer to design an imagined elsewhere or part of the process rather than an object for the sake of it. We see the designers turning to ancient or ancestral knowledge, to imagine how reconnecting with land, soil and nature could offer alternative ways of existing and belonging. Some artists seek to create connections with a more varied group of beings, including non-human and digital entities, to understand the world and mankind’s position in it. Several explore the human skill-set, and how feelings as opposed to thoughts can be a valuable and valid source of knowledge while navigating the future. Others imagine what our future surroundings – physical, digital and hybrid – could look like, and what behavior we may need to master to exist in these spaces.

While all dance to the beat of their own drum, the talents are connected by the idea that we are not alone in dealing with the challenges of our time. On the contrary: they show a deep-rooted conviction that everything is connected and that we may be hopeful, as long as we have each other. But most of all, they inspire us to see the silver lining. Instead of living a life of worry about the past or future, we can choose to be here, now. Trouble is a given, but life is a dance floor.

INTERVIEW DANCING WITH TROUBLE

DANCING WITH TROUBLE HAS BEEN COMPILED BY EVA VAN BREUGEL (AGOG AND URBAN ENVIRONMENT PROGRAMME MAKER), ESTHER MUÑOZ GROOTVELD (PROGRAMME MAKER AND STRATEGIC CONSULTANT AT THE INTERSECTION OF FASHION, DESIGN, ART AND SOCIETY), AND MANIQUE HENDRICKS (CURATOR, WRITER AND RESEARCHER IN THE FIELD OF CONTEMPORARY ART, VISUAL AND DIGITAL CULTURE). MARIEKE LADRU AND SHARVIN RAMJAN, BOTH ASSOCIATED WITH THE TALENT DEVELOPMENT GRANT SCHEME OF THE FUND, SPOKE WITH THE THREE PROGRAMME MAKERS.

HOW DO YOU SEE THE IMPORTANCE OF TALENT DEVELOPMENT?

EB ‘I think talent development is essential. We are facing huge transitions in the field of housing, energy, water, greening and sustainability; in short, a changing society and culture. We need a new vanguard to effectively take on this challenge. The new generation can bring a fresh perspective and different approaches.’

MH ‘The challenges are relevant professionally, but are also issues we need to relate to as human beings. And that’s quite demanding, also for these young makers. While the first years following graduation are already quite challenging. That’s why the talent development grant is so important. Besides offering time and funding, it gives the recipients the opportunity to develop focus, to present yourself to the world, and to engage in collaborations and forge connections.’

EMG ‘One of the important values of the grant is that it enables talented makers to meet each other. That way they can move ahead together, which builds confidence. Talent is often the vanguard since they still have a certain open-mindedness. They look toward the future with hope, and move toward the future with boldness and freedom. I think that’s wonderful to see.’

WHAT TYPIFIES THESE MAKERS?

MH ‘The hope that Esther refers to is certainly striking. These makers do not envisage a dystopian future. They are aware of living and working in a complicated time, but they want to ride the waves. Being part of a collective is an important part of it. That’s why the programme was titled Dancing with Trouble. Each individual chooses their own rhythm, but they are in this together.’

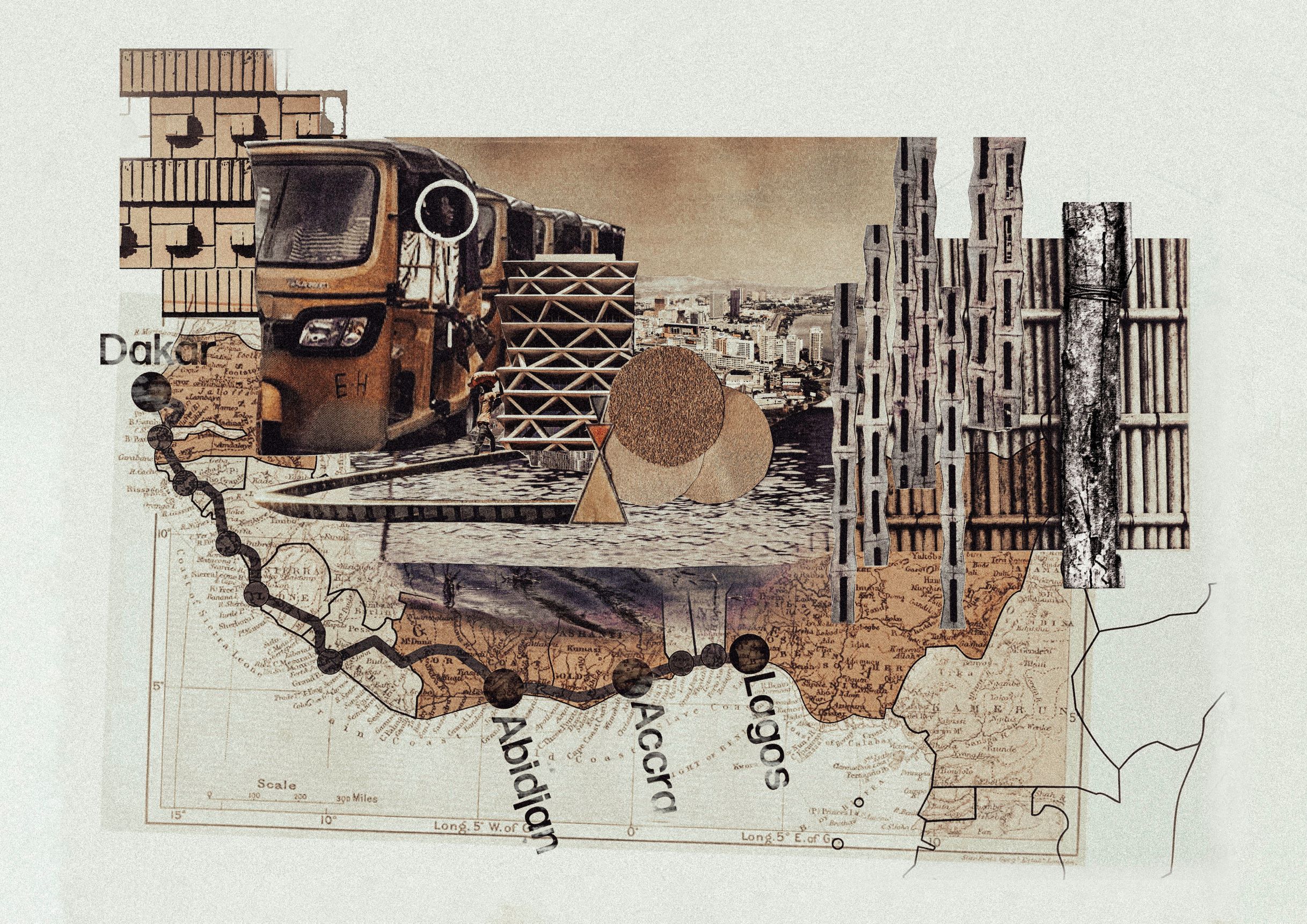

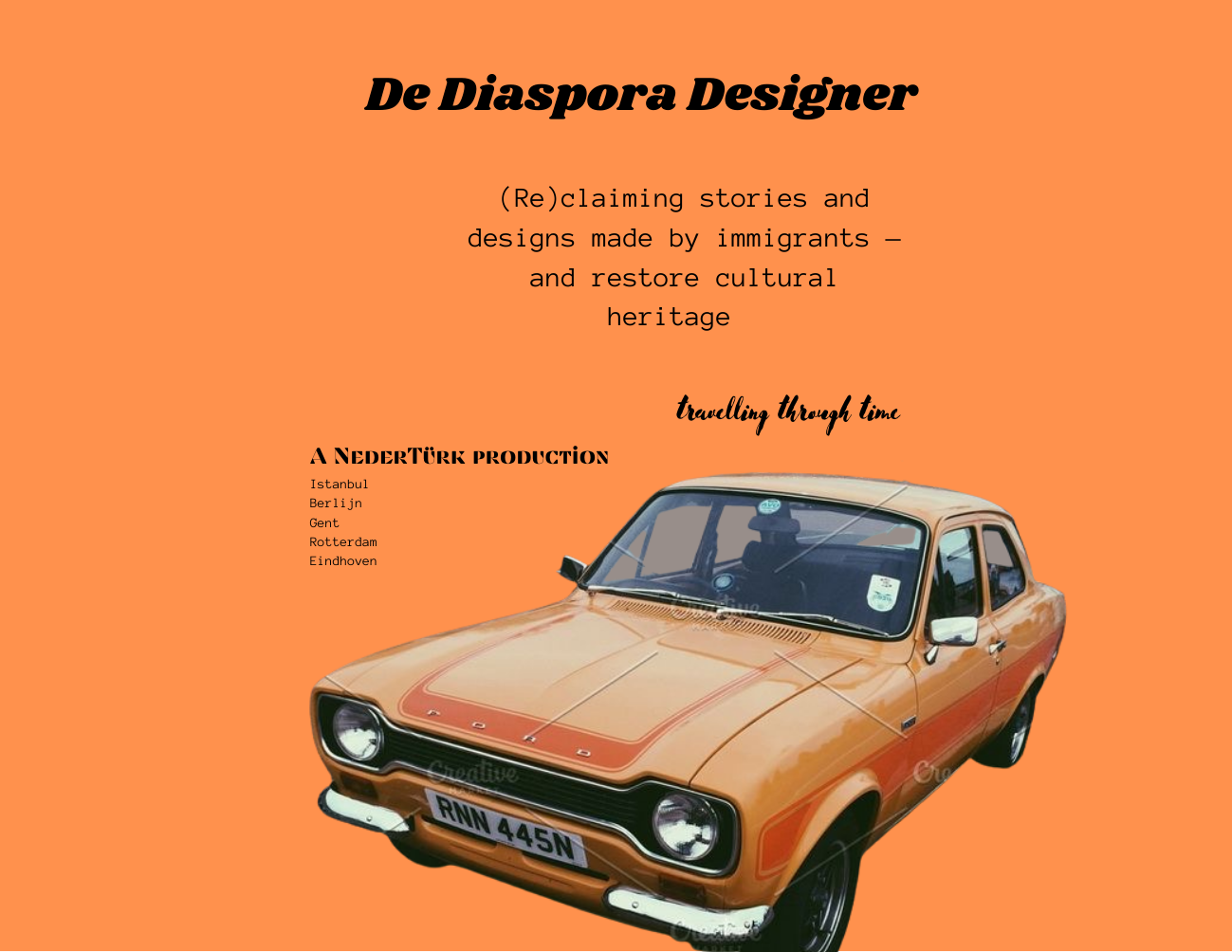

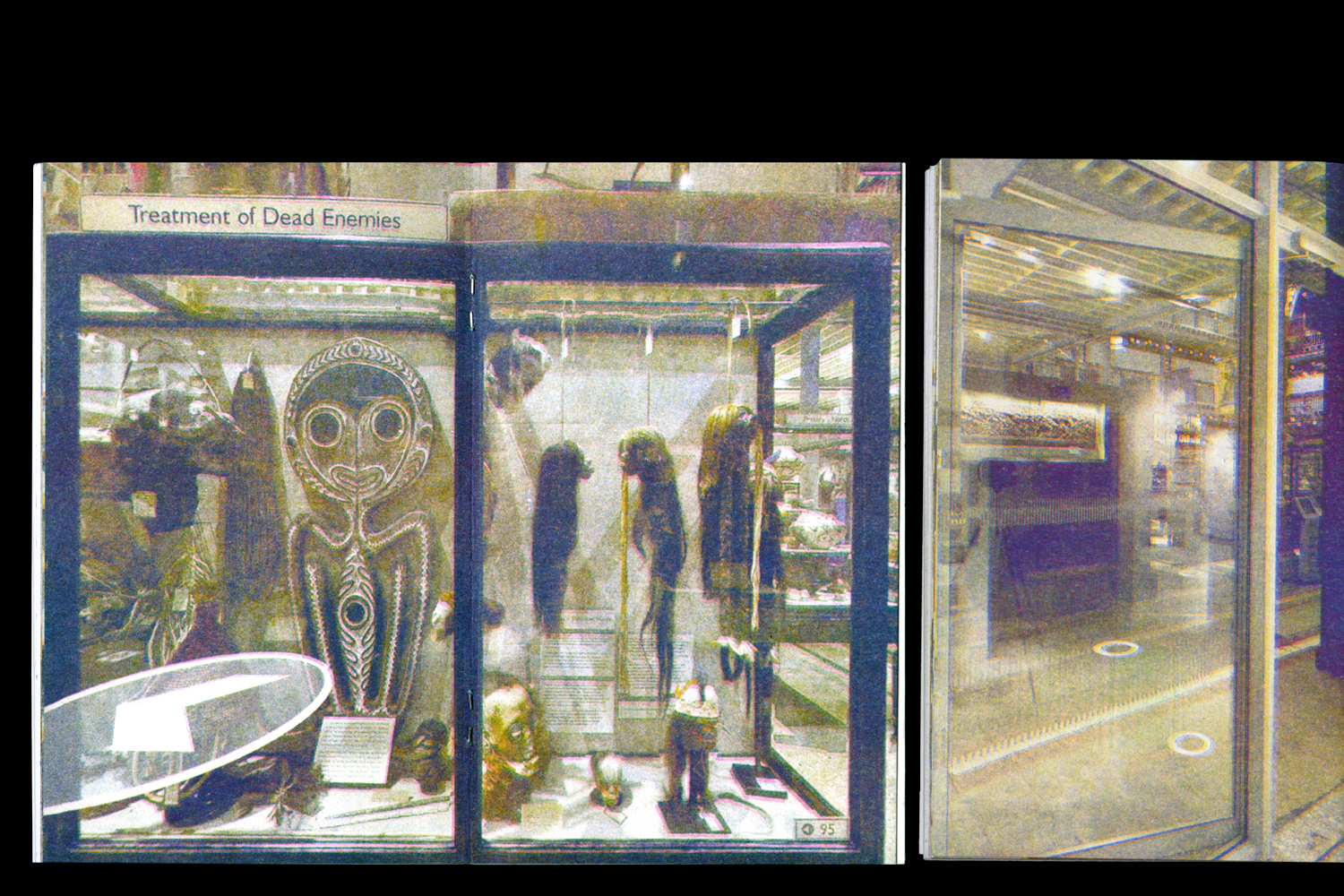

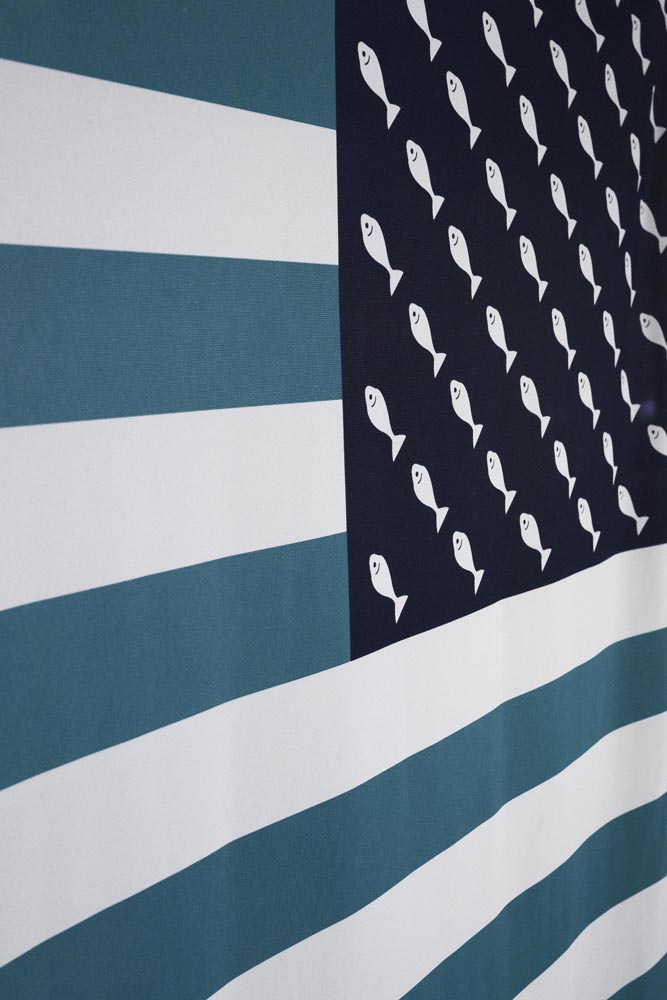

EB ‘Many makers focus on personal themes such as identity, queer community and diaspora, but also engage with the current crises in the world concerning the climate, the changing landscape, available agrarian land and migration. Who has the right to claim a certain space? That’s a relevant question in a physical sense, but also philosophically and culturally. Design and research interrogate the status quo by finding new ways to look at what’s here now.’

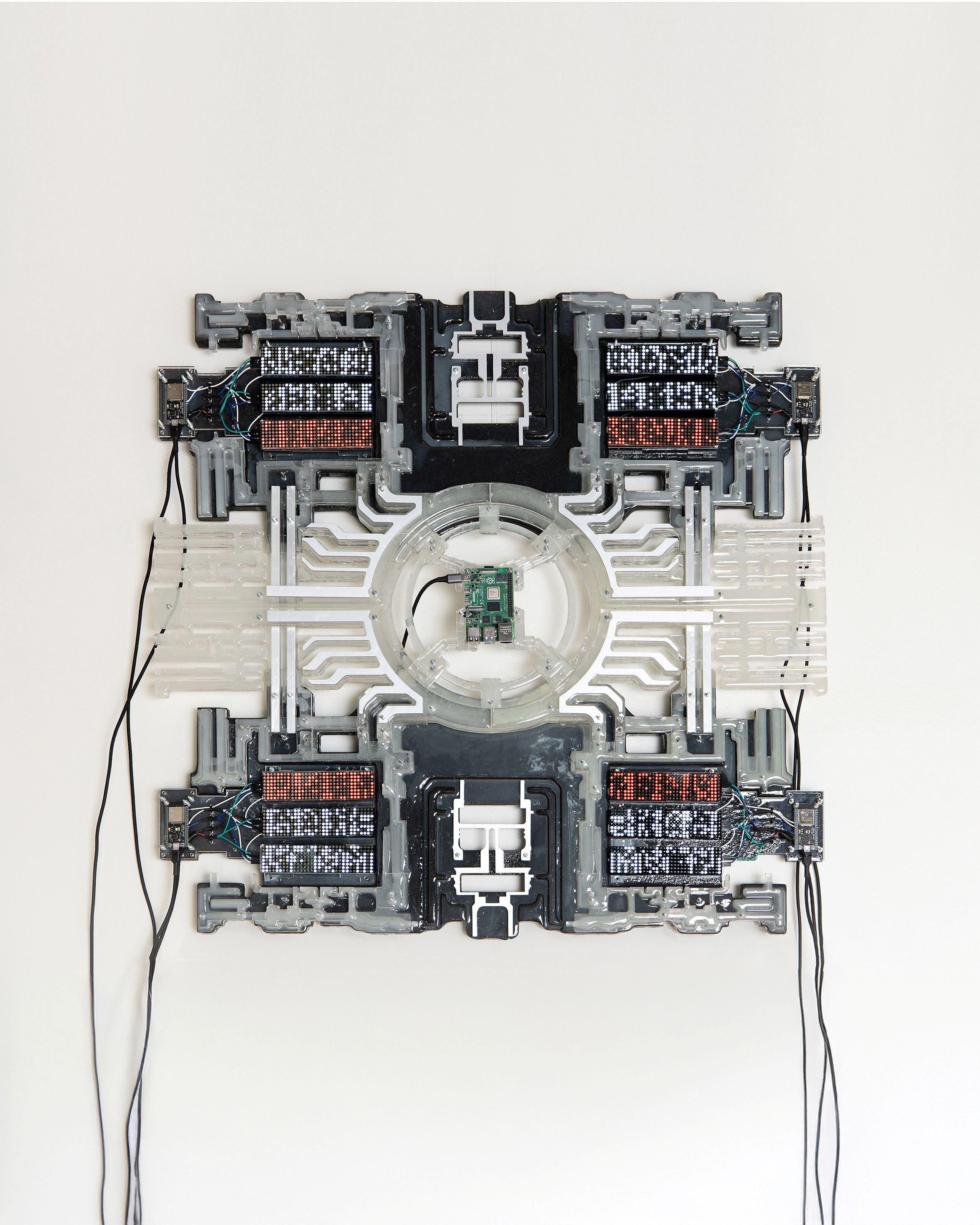

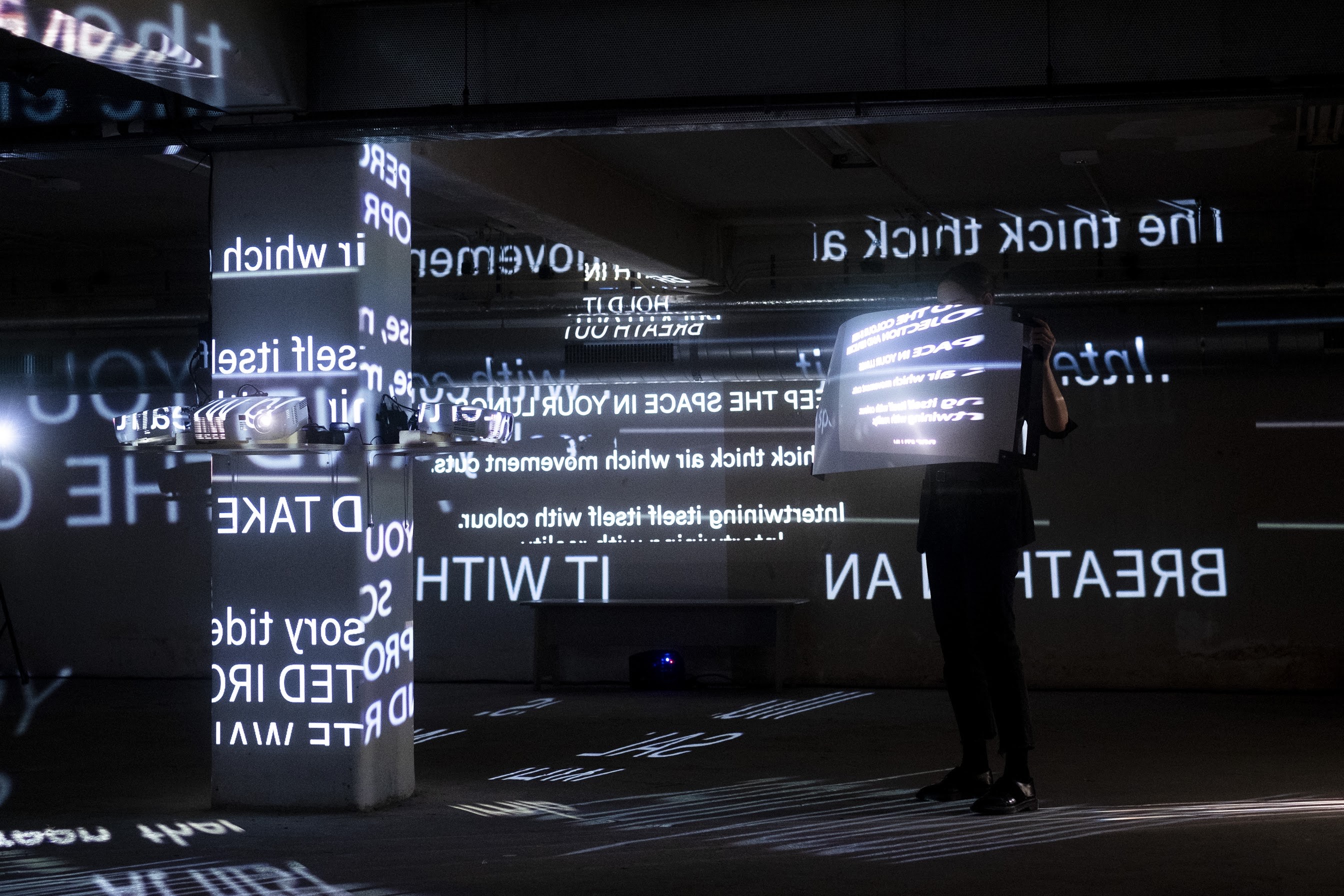

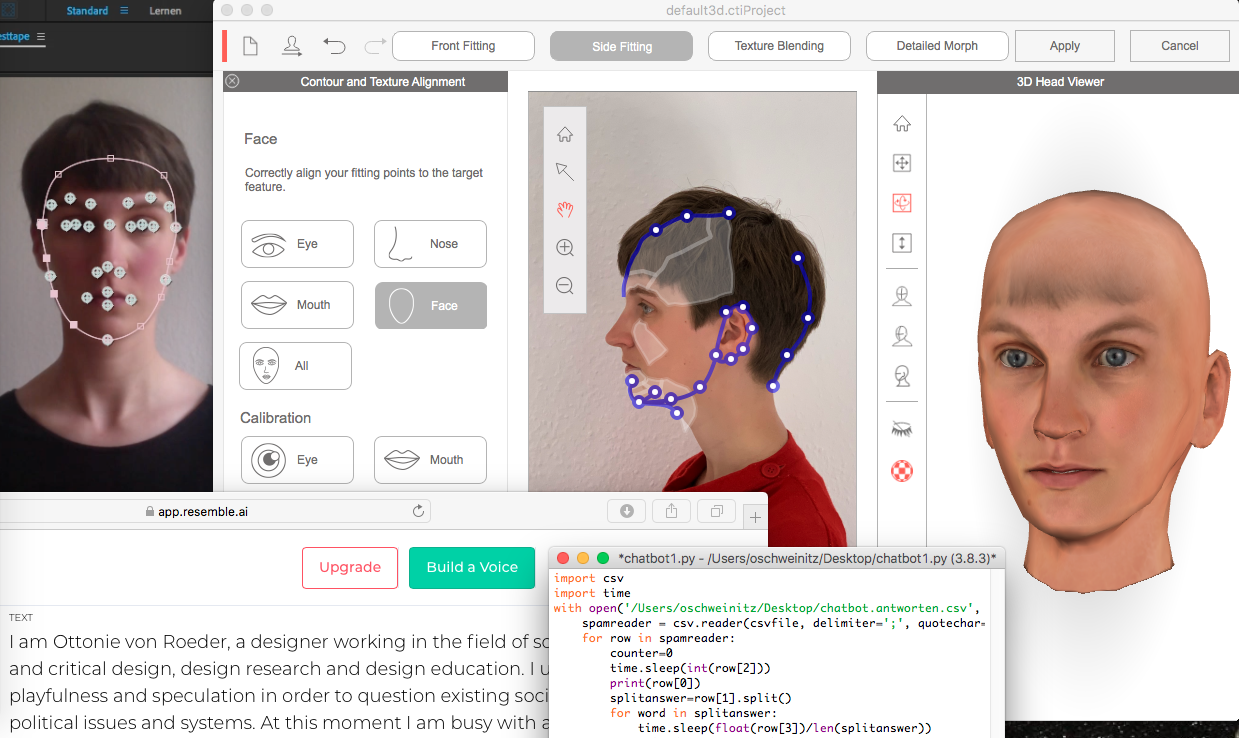

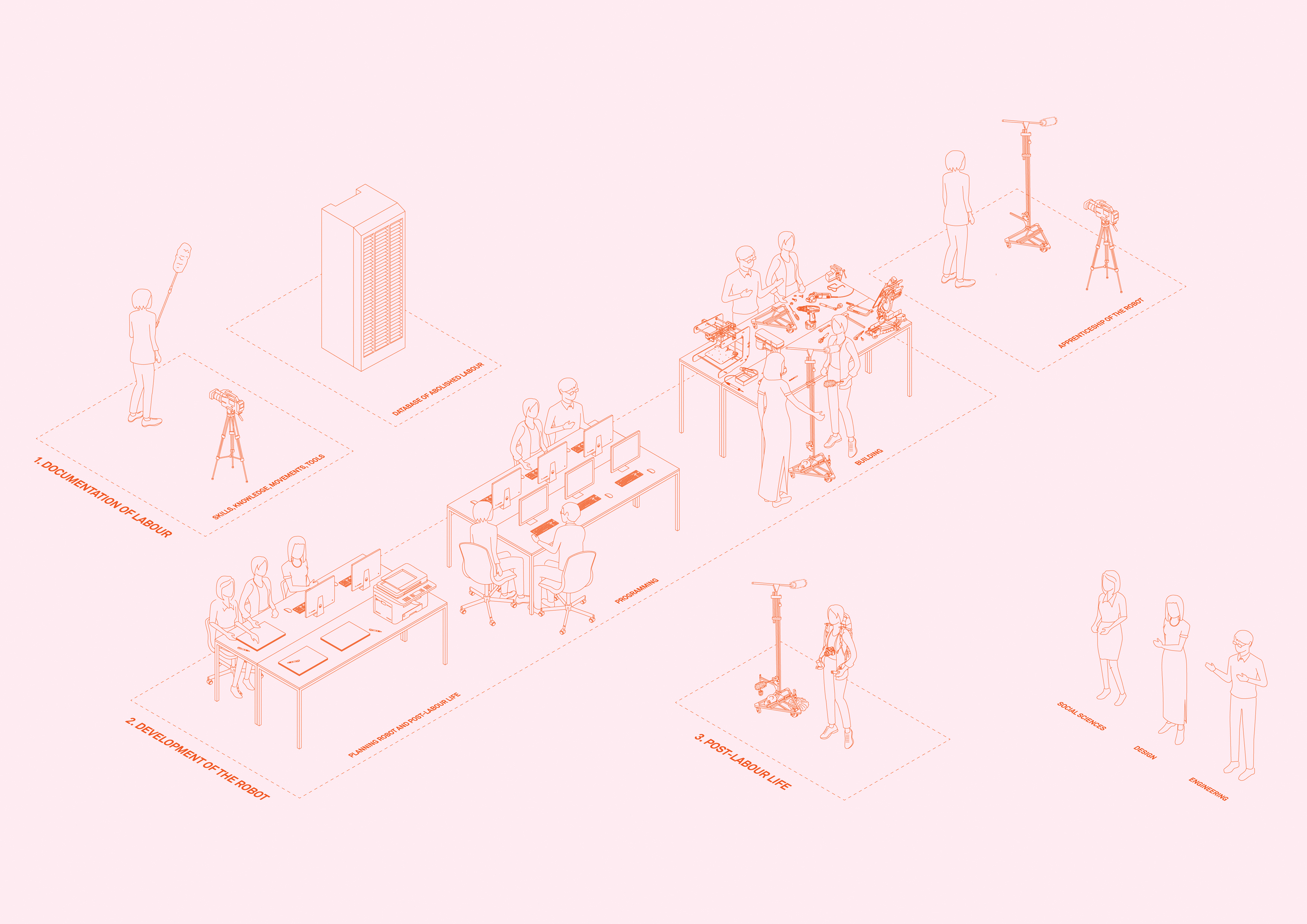

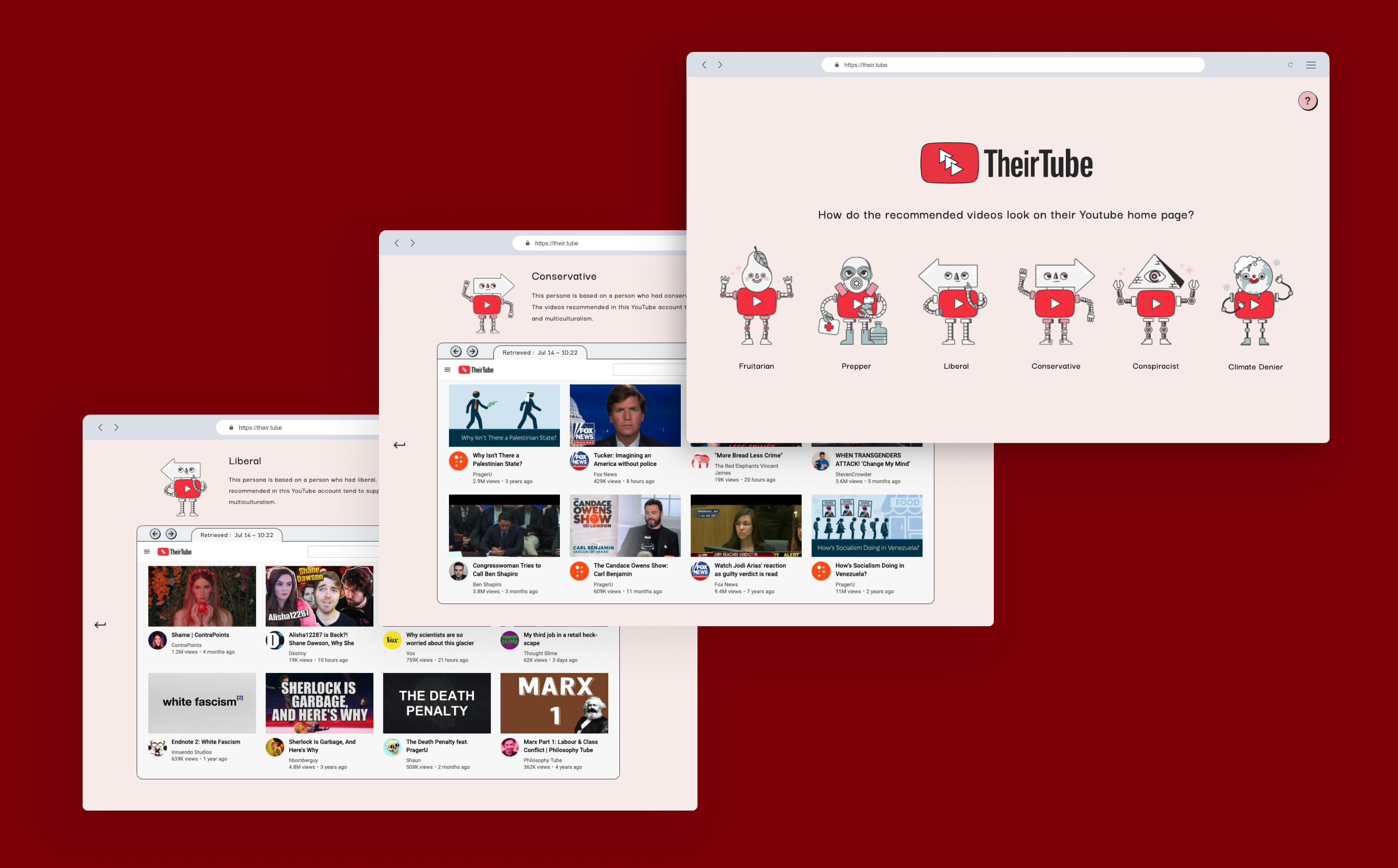

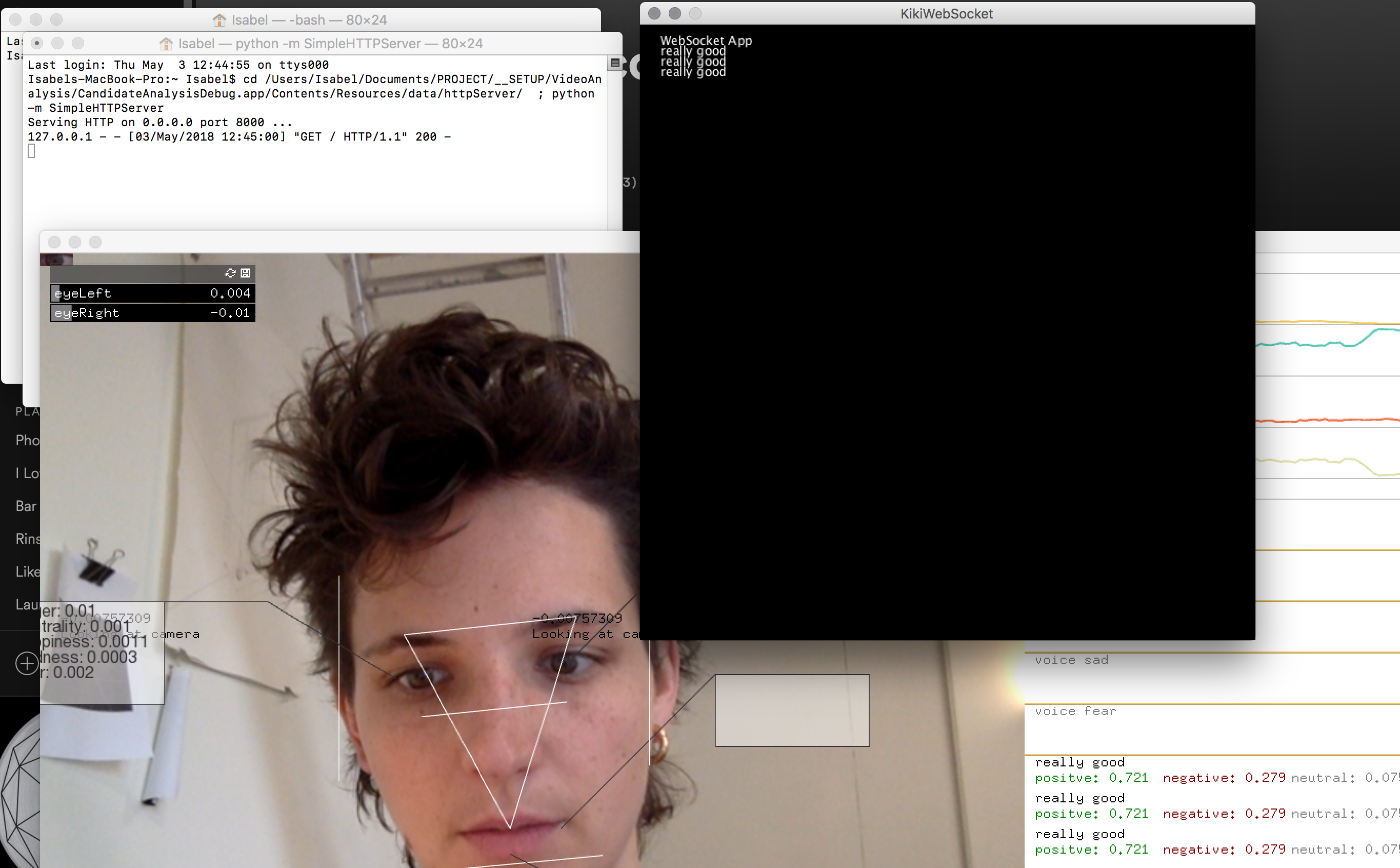

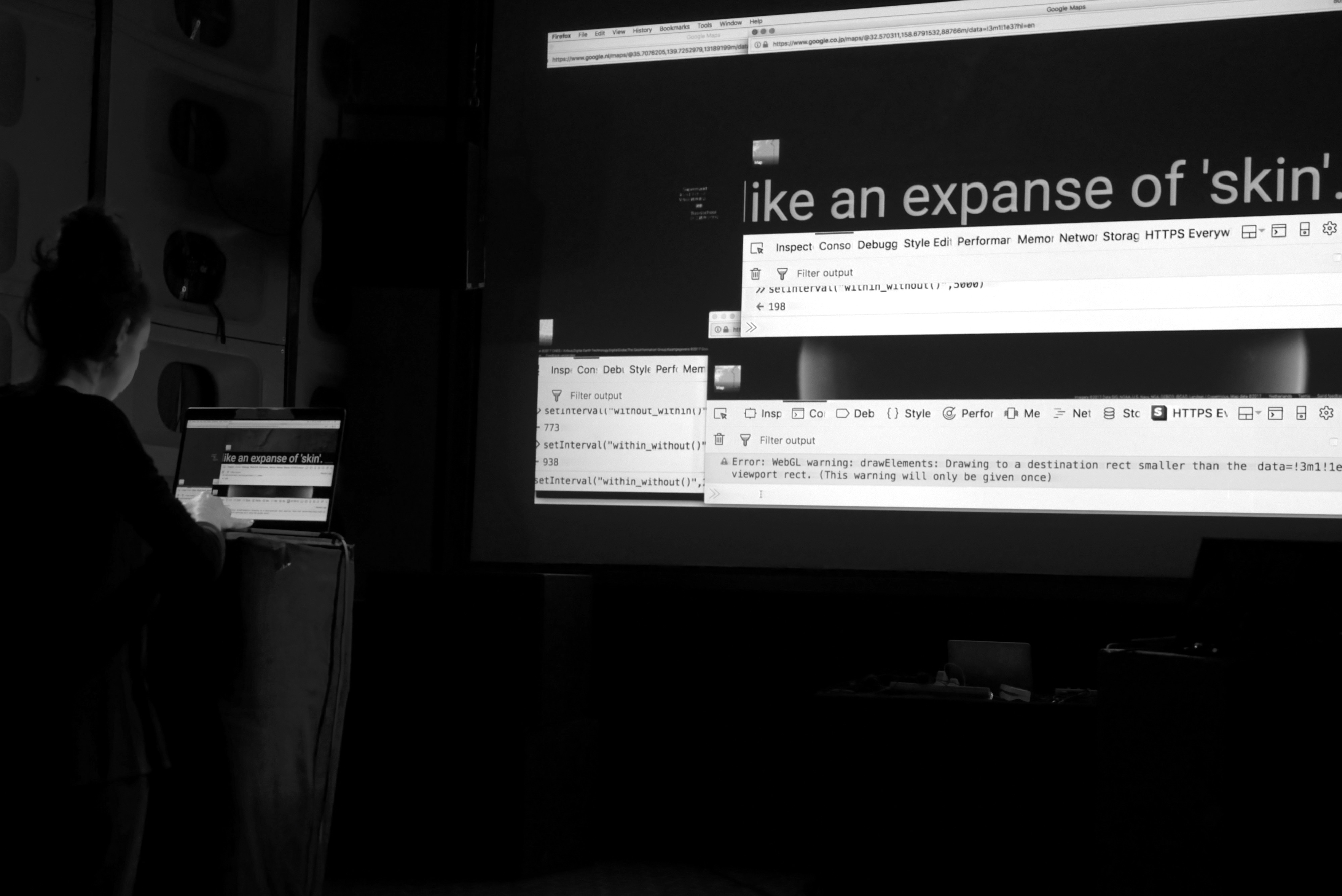

MH ‘The lived experience often takes centre stage. How can you communicate this? This is attempted for instance by means of technology, enabling the user – or the audience – to empathise with others, to share experiences and to build communities. It involves creating and appreciating other forms of knowledge transfer.’

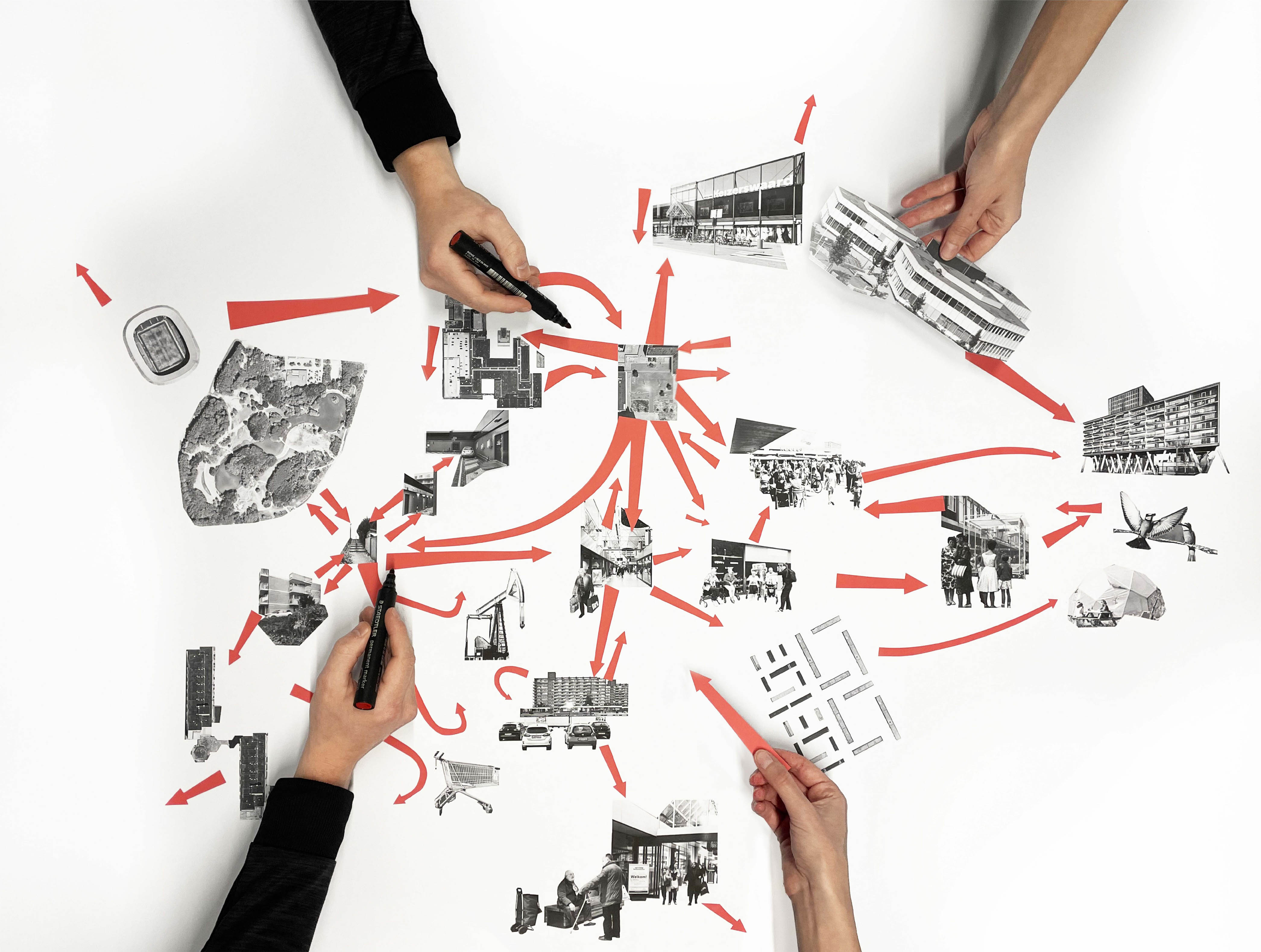

EMG ‘What seems to characterise this group of upcoming makers is a holistic approach and a desire to connect with the environment and the future. Designers are working on shaping and developing relationships and connections. The physical object often seems to be of secondary importance; what really matters is stimulating a dialogue or change process.’

EB ‘The emphasis is often on the process and the experiment, with less concern for an end product or goal. I also notice that these talents show a very adaptive approach to the current time of transition.’

DOES THIS IMPLY ANY PARTICULAR CHALLENGES?

EMG ‘The absence of a tangible end result can make it more difficult to present a story. Of course a picture is worth a thousand words; but projects that address complex issues are often hard to capture in language. For some designs, there simply isn’t any vocabulary yet.’

EB ‘Perhaps it’s also easier to work on a concept, and in this phase of your professional practice it might be difficult to take a certain position and then to materialise this in a product or end point. But then this might also be a particular quality of the new generation!’

HOW MIGHT THE EMERGENCE OF HYBRID PRACTICES AFFECT THE FUTURE OF THE DESIGN FIELD IN RELATION TO THE VISUAL ARTS?

EMG ‘The connection with visual arts is quite particular for the Dutch design sector. Designers are often trained at art educational institutes that are all about artistic expression. So it’s no surprise that the distinction between design and visual art isn’t always clear-cut. What I find more interesting is how makers are increasingly investigating other disciplines such as biology or geology. This leads to collaboration projects in which the designer acts as the linchpin.’

EB ‘Designers and artists are increasingly adopting interdisciplinary approaches, and are developing more rapidly than the underlying systems. This causes some complications in the work field. For example, grant schemes often presuppose that designers can be categorised in terms of discipline. And having a complex profile can also make it difficult to obtain commissions.’

EMG ‘Indeed, a hybrid practice can be difficult to pigeonhole. Certainly in the world of institutions, it can be hard for these practices to fit in. The makers face questions such as: how do I claim my position in the field? How do I demonstrate the relevance of my work? And how can I obtain funding for my work? This can be difficult for design research, which doesn’t have a clearly projected end result. Not many clients are willing to accommodate experimentation. These designers need to think carefully about the partners in industry

and other disciplines that they want to involve in their work.’

CAN YOU TELL US A BIT ABOUT THE FIVE THEMES THAT MAKE UP DANCING WITH TROUBLE?

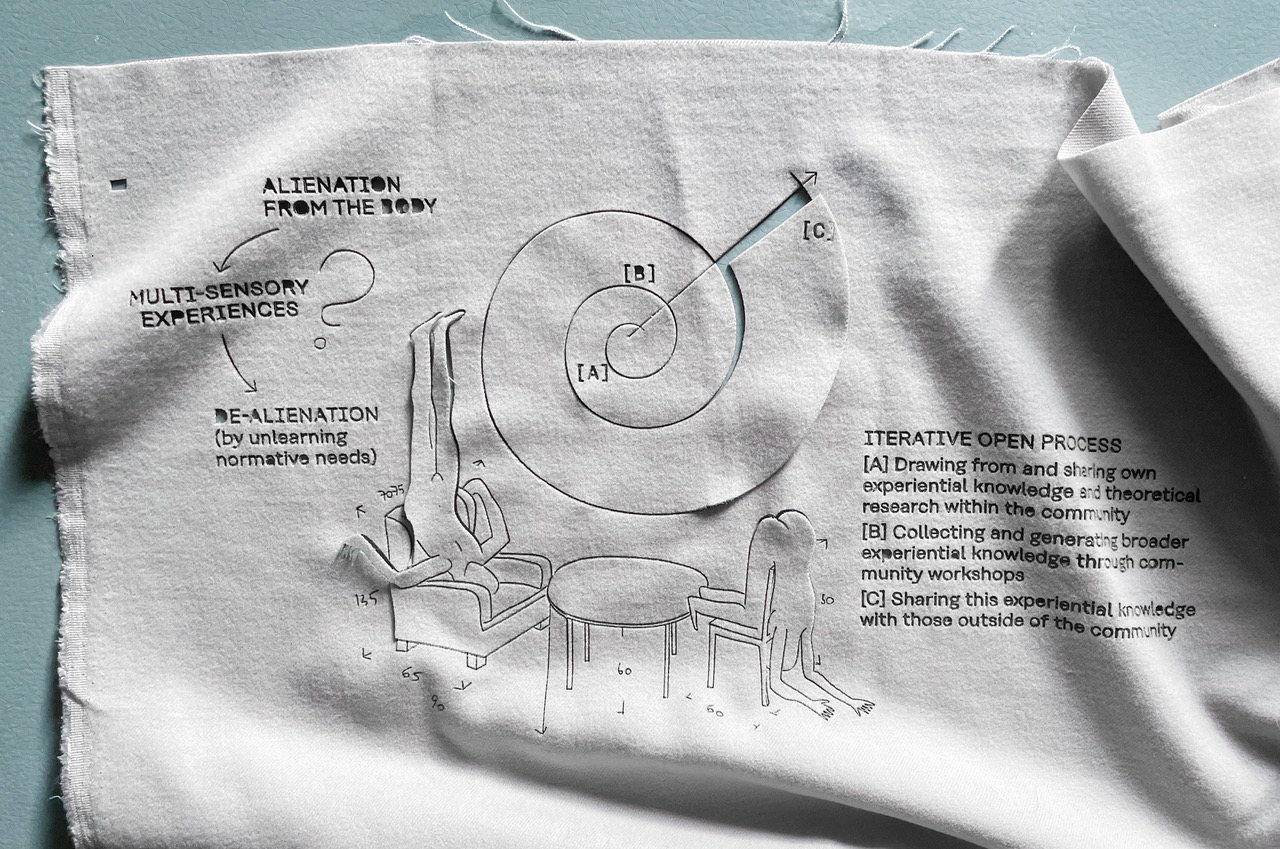

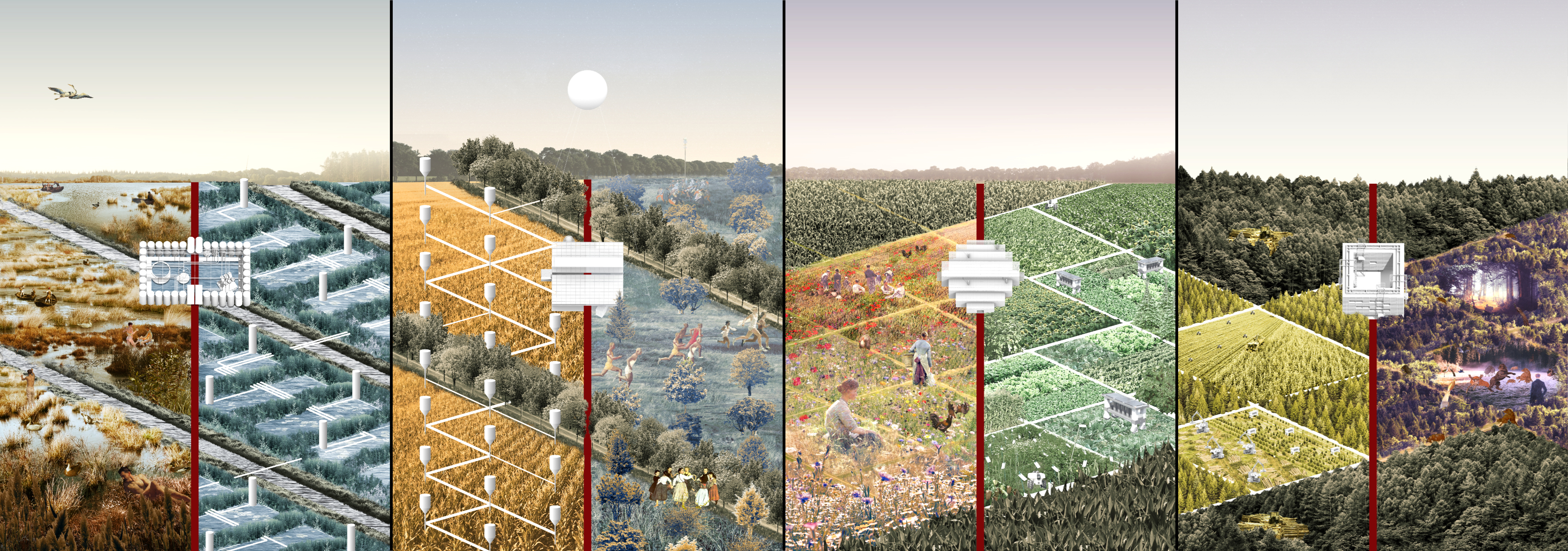

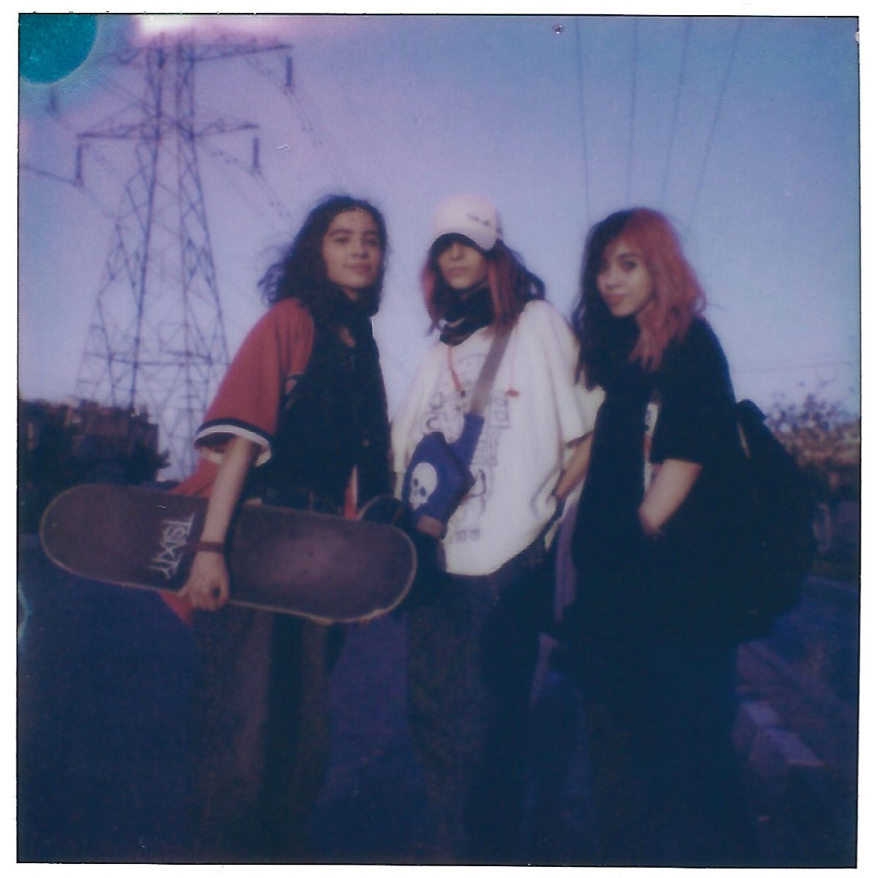

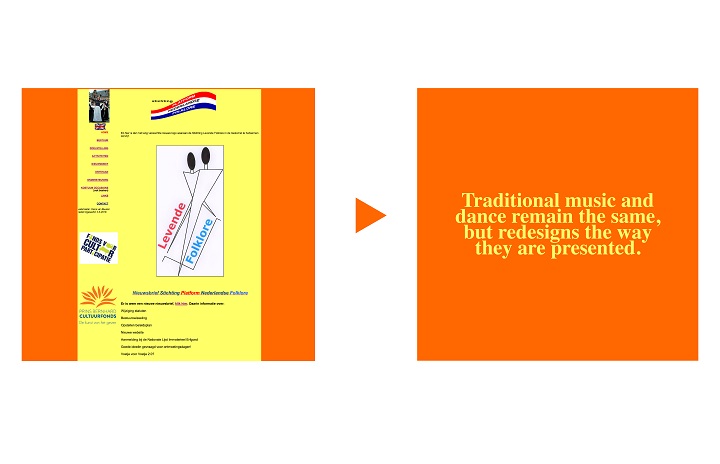

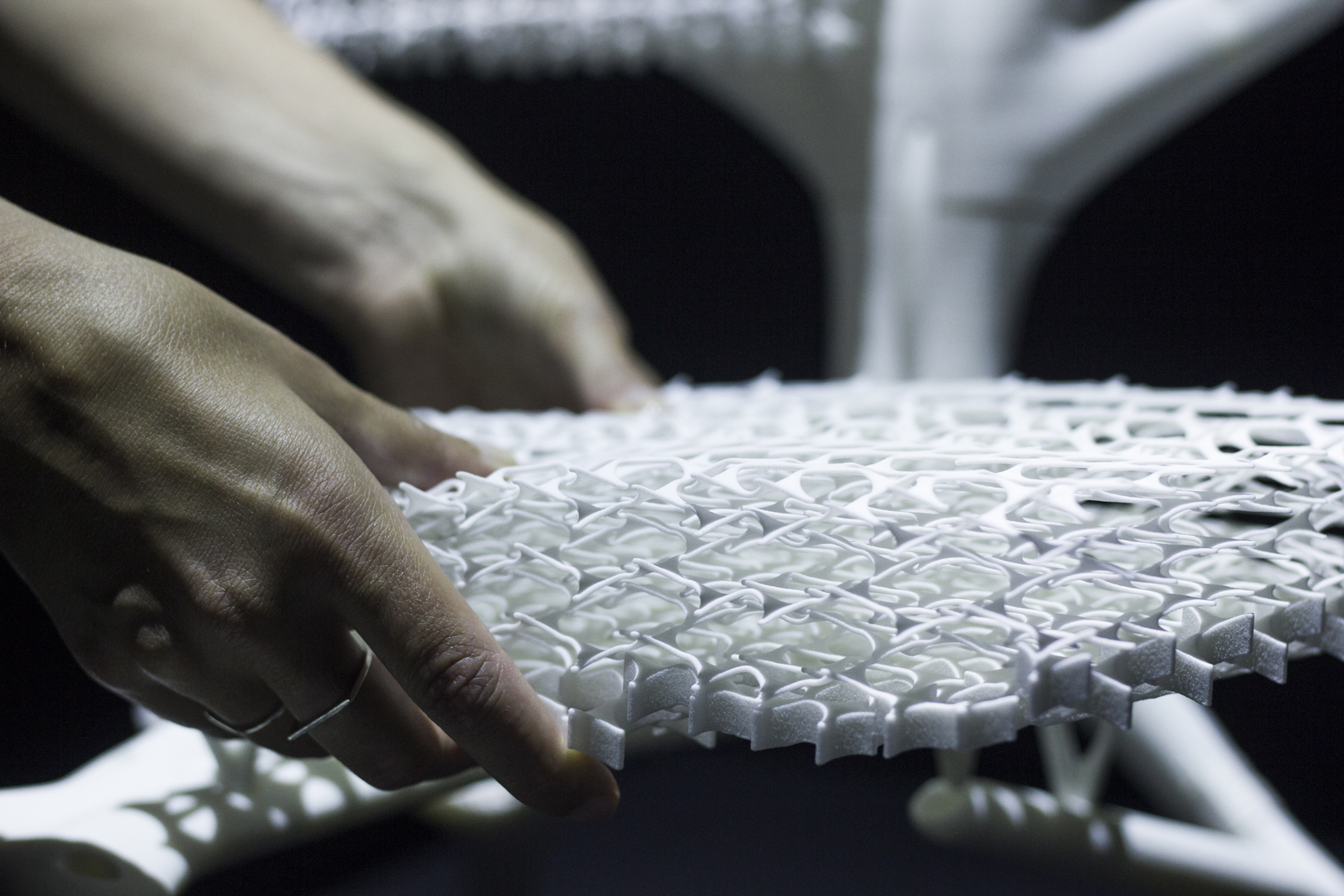

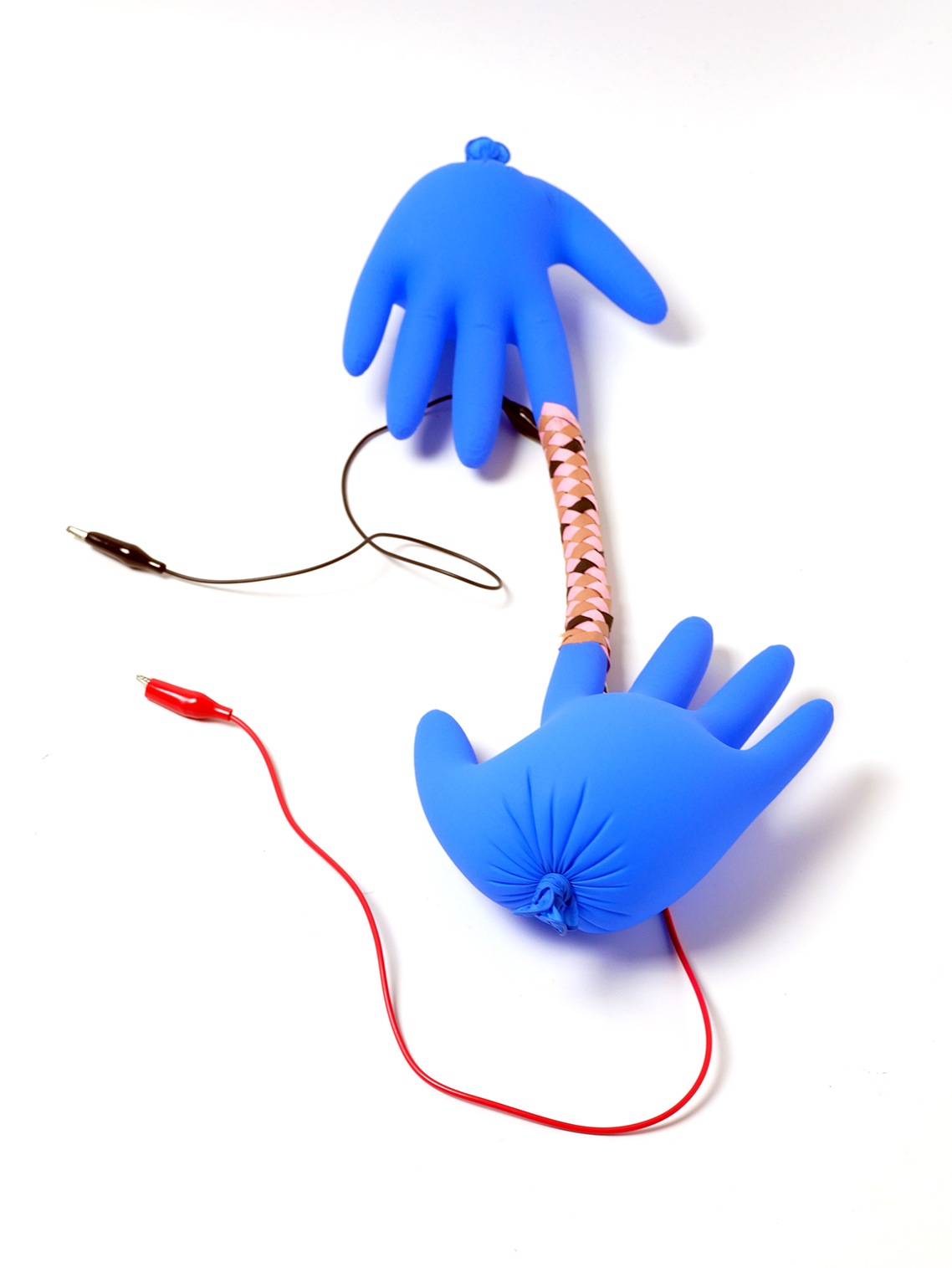

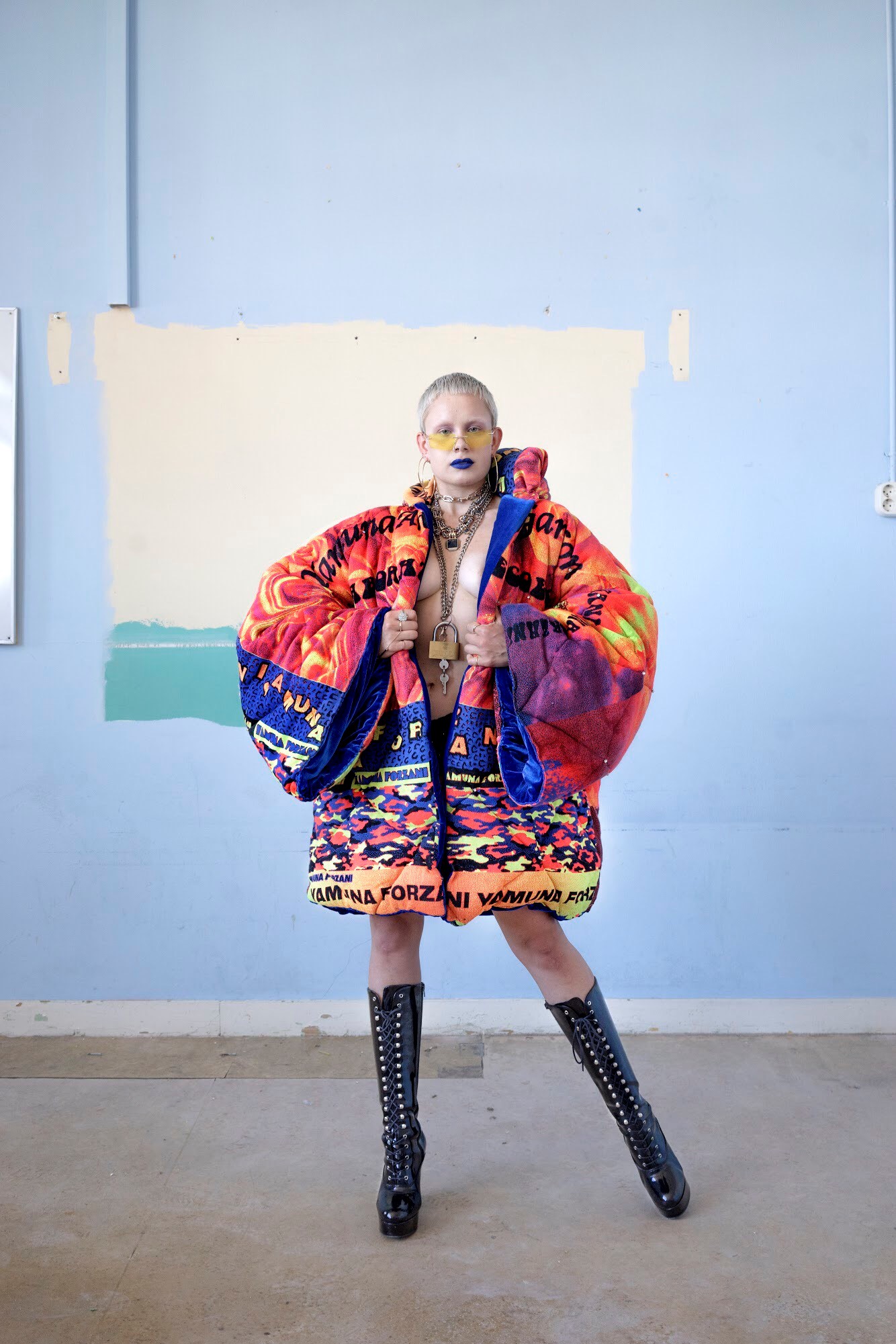

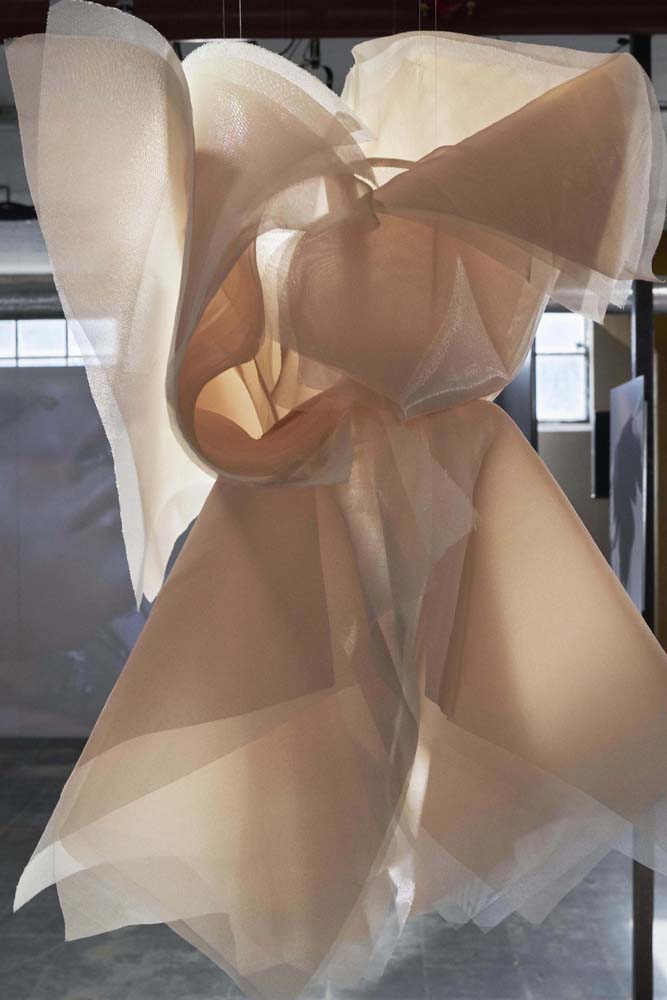

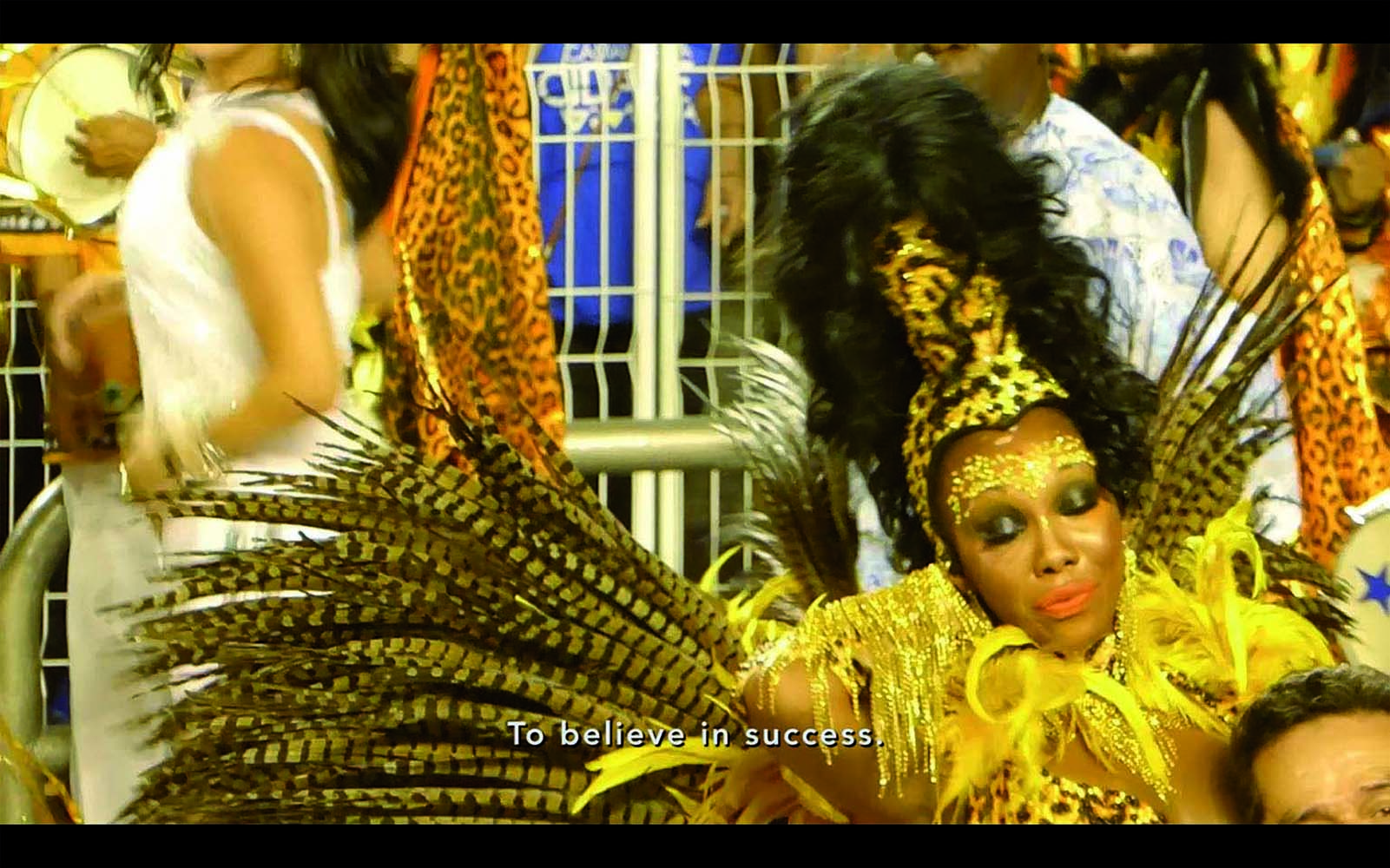

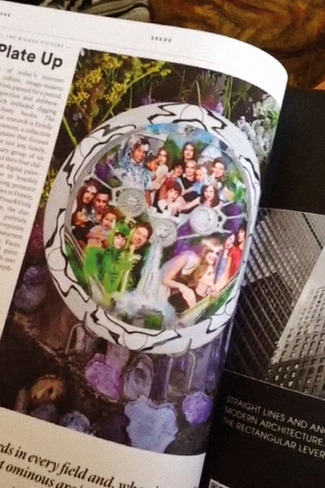

EMG ‘We distinguished five themes that inform and connect the different presentations and performances during the Dutch Design Week 2022. The theme of Sensing Forward pertains to the increasing acknowledgement of emotions and experiences as a valuable and valid source of knowledge. A good example is the work by product designer Boey Wang, who explores how you can design on the basis of touch and feeling. Beyond Bodies is about no longer seeing the human being as central but learning to listen to nature and other entities. Thus, Dasha Tsapenko offers a glimpse of the dressed body in the future by examining how we would dress if our items of clothing were living beings. Relating to Land(scapes) focuses on future landscapes and the new skills and behaviour we need to develop to live and navigate communally. For example, Lieke Jildou de Jong examined what would be the best diet with a view to the soil. Longing to Belong addresses the sense of rootlessness that many people have in this hyper-individualist era. What does it mean to “feel at home”, and how can designers contribute to a sense of togetherness? Finally, Power to the Personal focuses on practices in which personal stories play an important role.’

MH ‘These themes reflect the mood and the movement apparent among this group of designers and makers. It is special to see so many new ideas juxtaposed. And the fact that this group also consists of makers that were not previously represented in the sector is cause for optimism.’

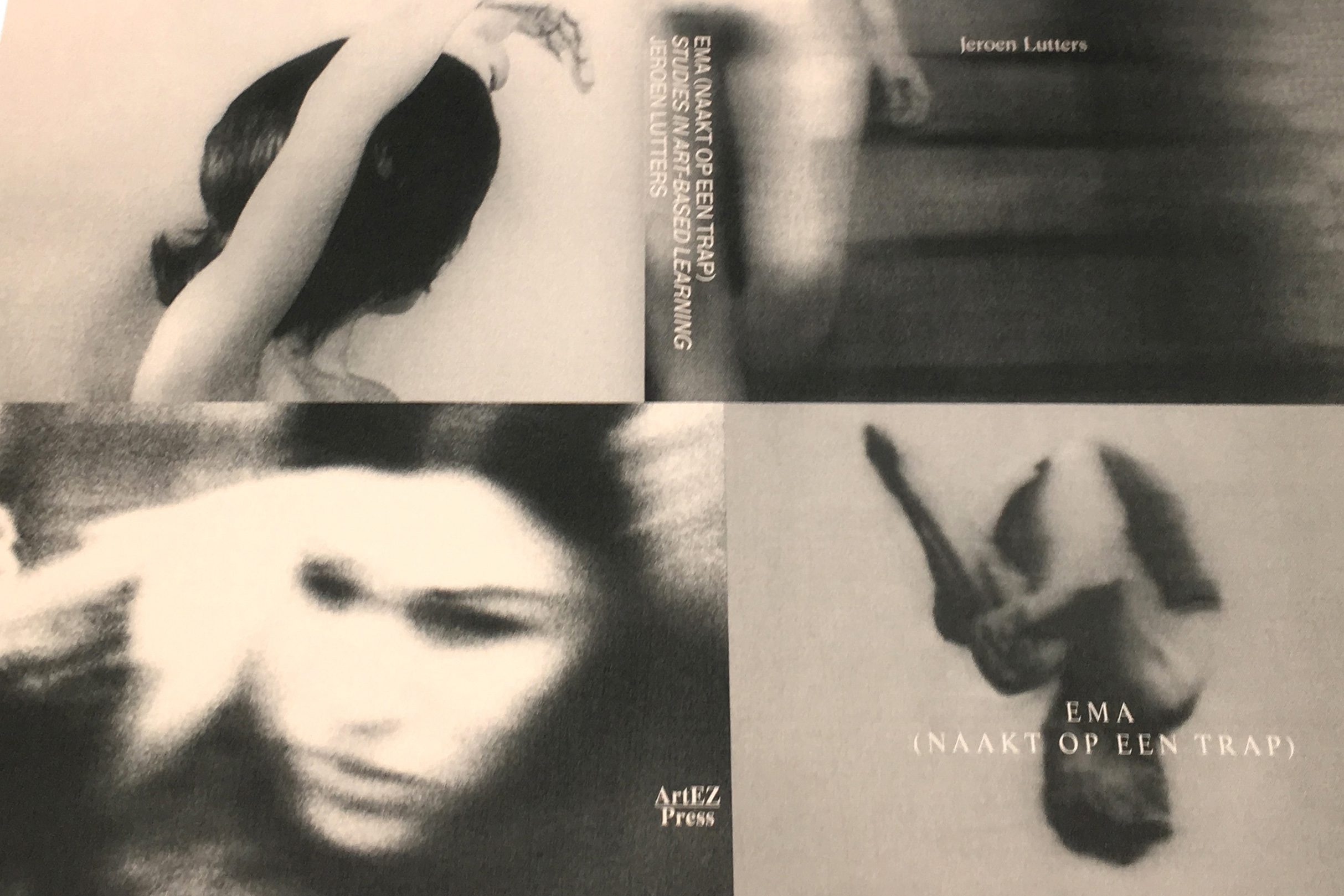

Longread Talent #1

Me and my practice

How design talents (have to) reinvent themselves

Over the past seven years, the Creative Industries Fund NL has supported over 250 young designers with the Talent Development grant. In three longreads, we look for the shared mentality of this design generation, which has been shaped by the great challenges of our time. In doing so, they examine how they deal with themes such as technology, climate, privacy, inclusiveness and health. In this first longread: the in-depth reflection on the field and place of their own practice in it. The entrenched principles of fashion, design and architecture are questioned and enriched with new tools, techniques, materials and platforms.

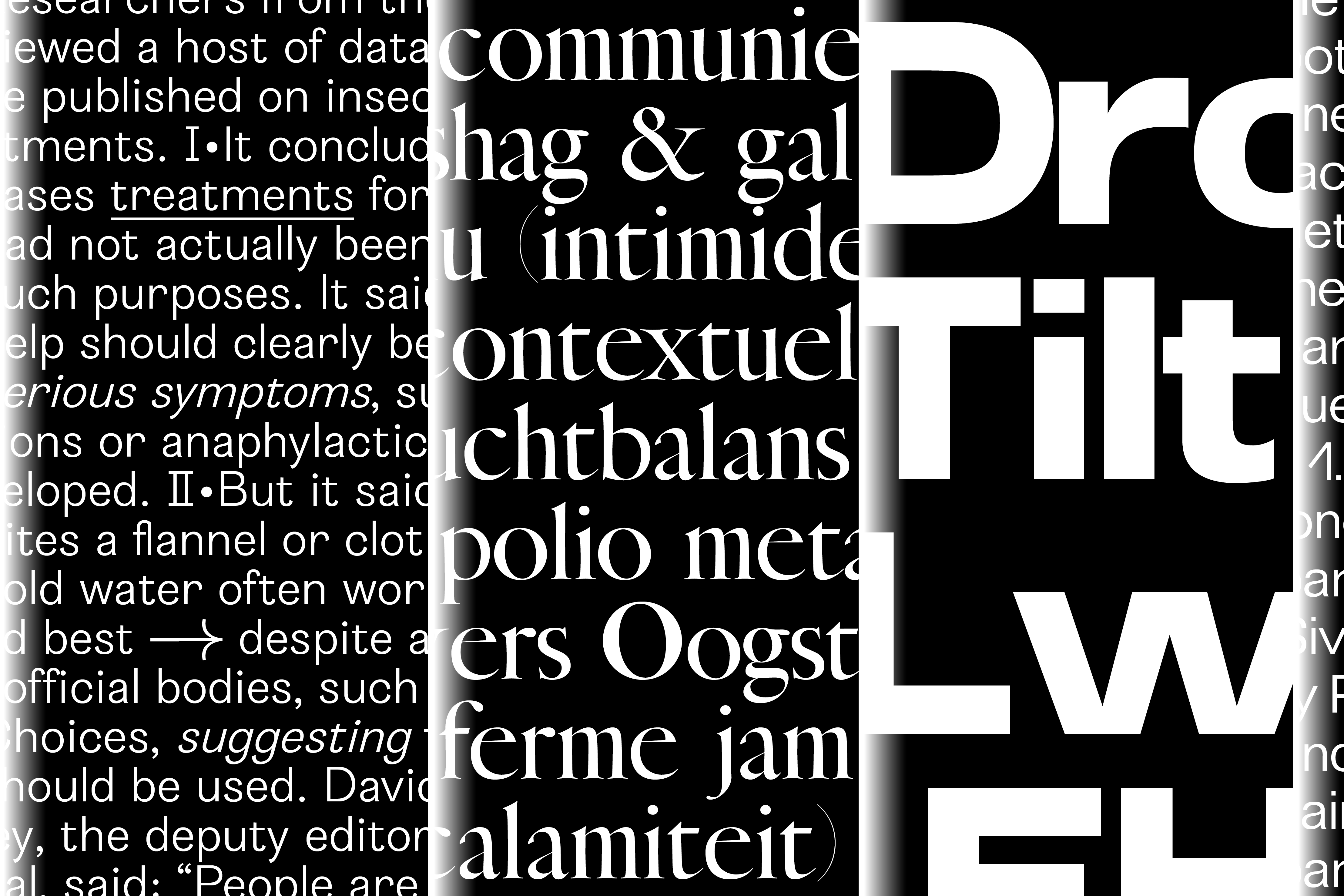

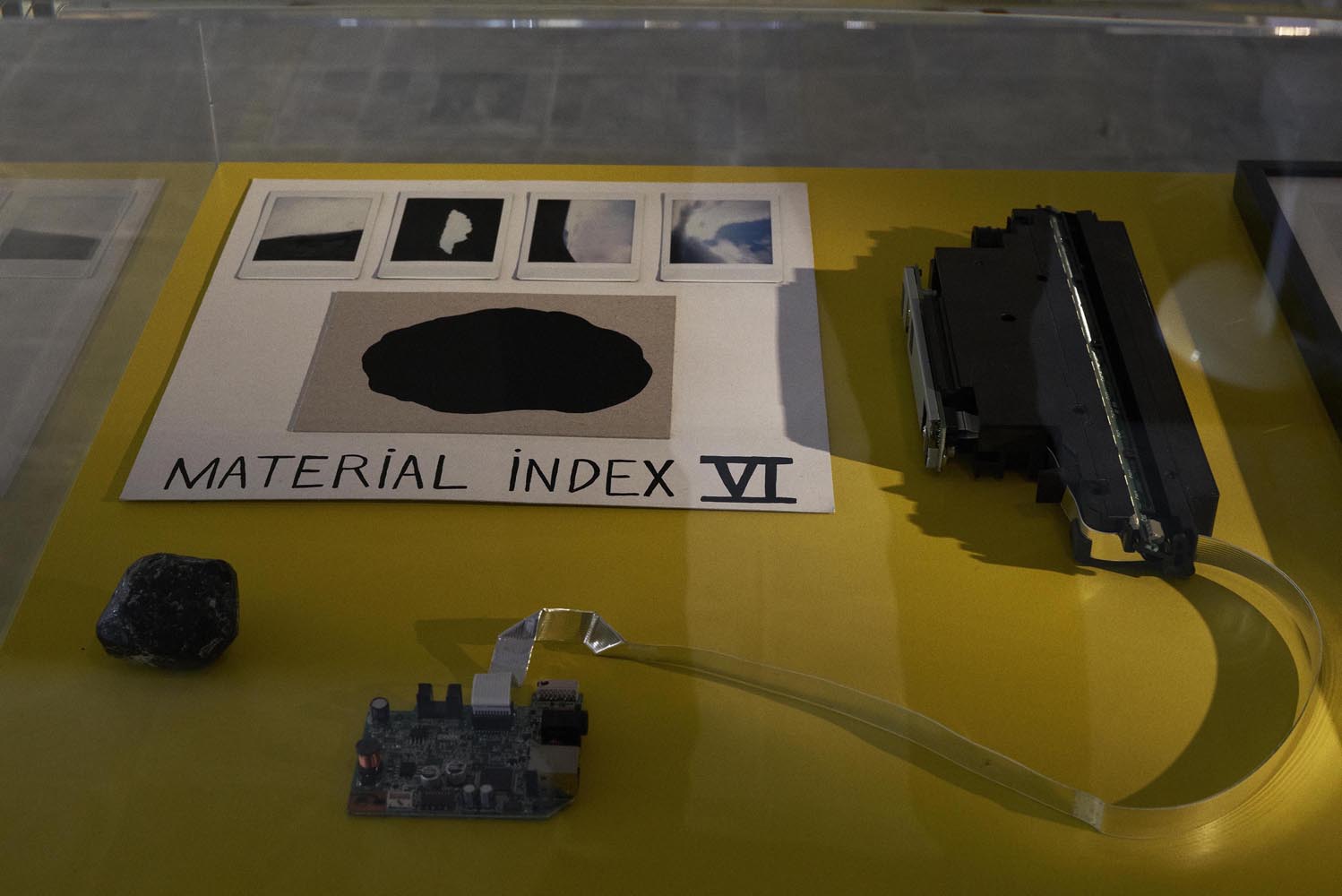

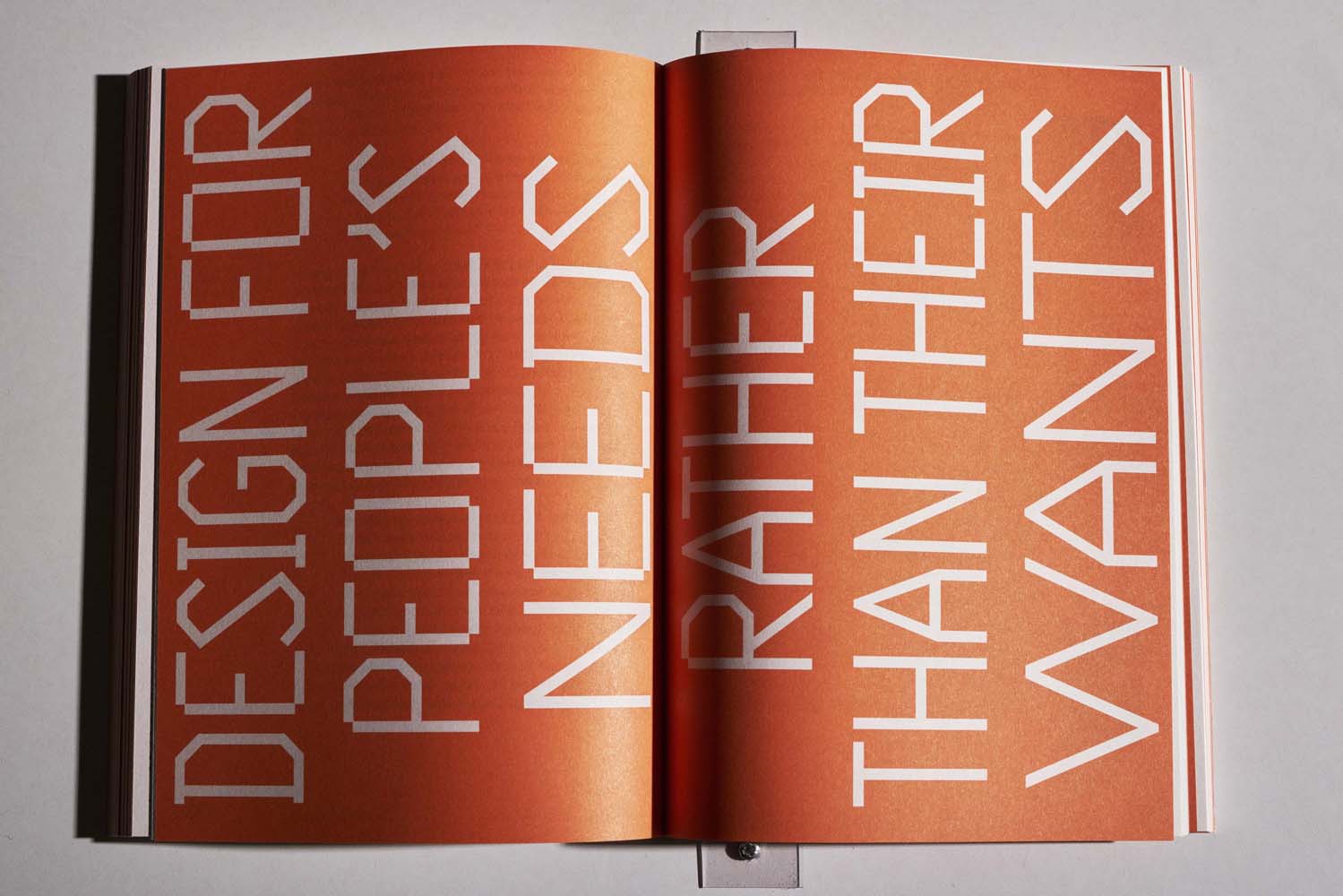

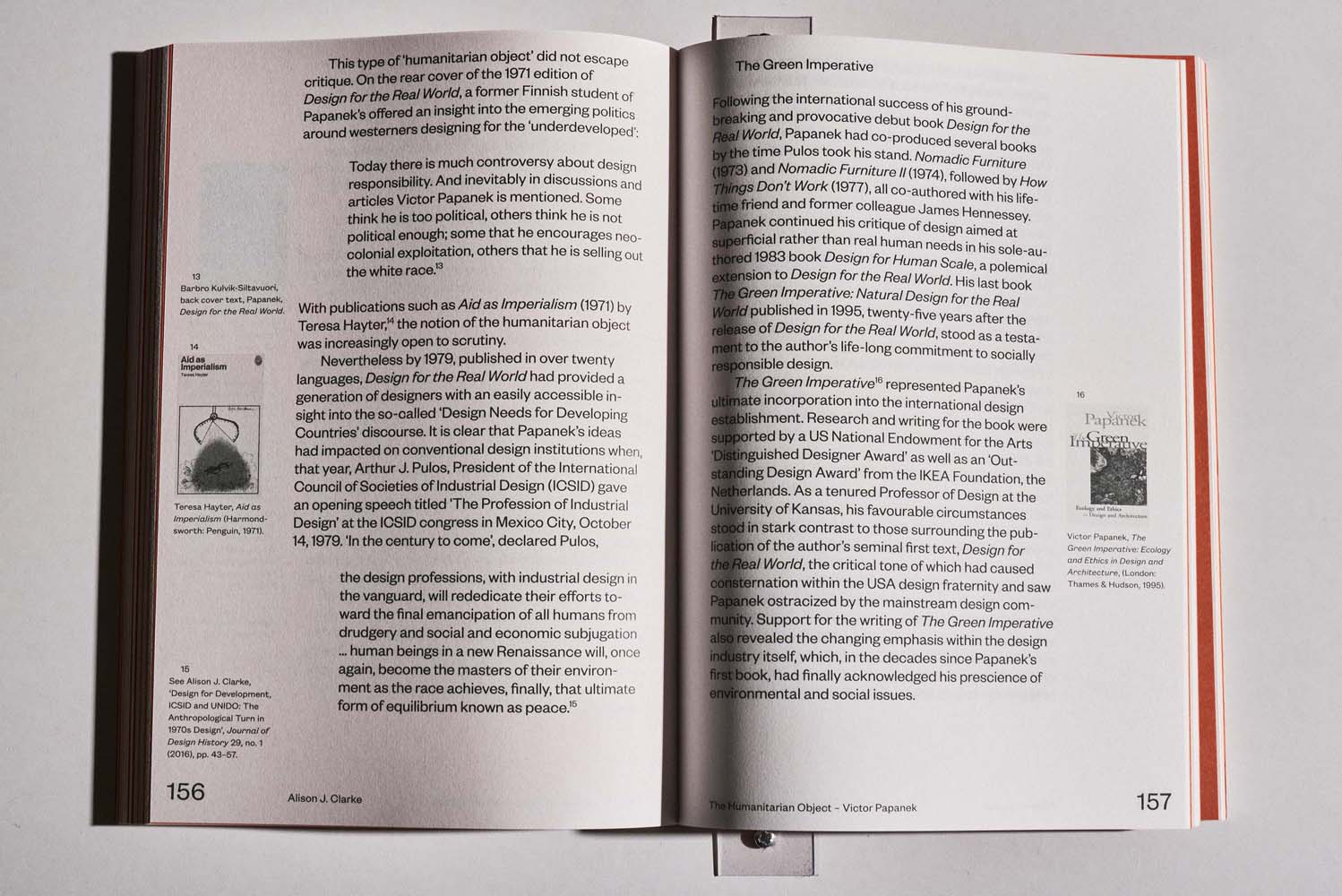

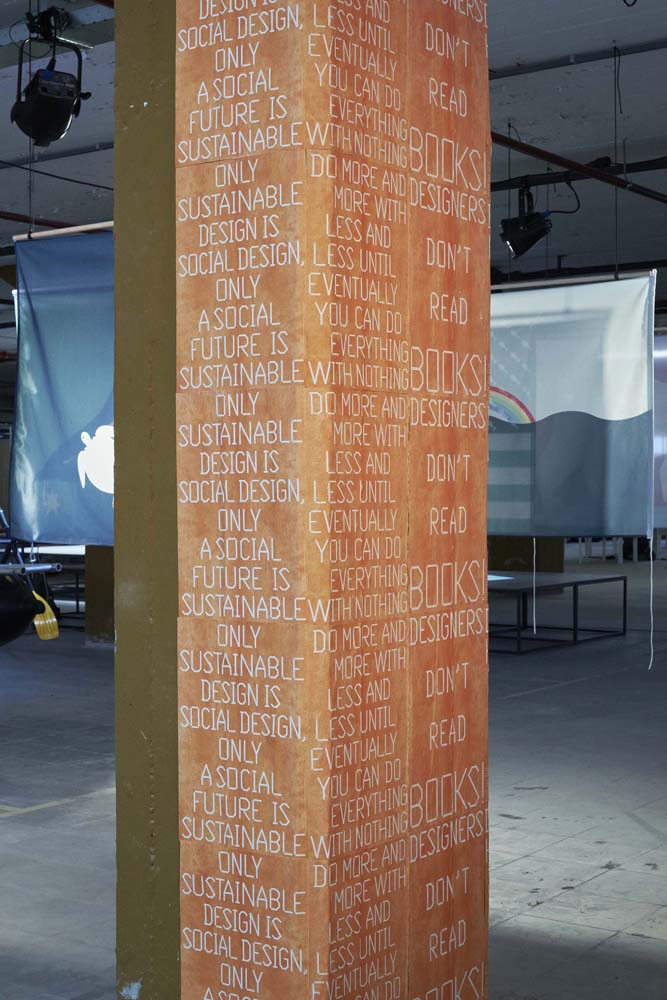

The Dirty Design Manifesto by Marjanne van Helvert is a fiery argument against the fact that the production of many design objects causes

so much pollution. It also takes a stand against tempting design products, without individuality or intrinsic value, fuelling consumption. The manifesto focuses

not only on manufacturers and consumers but also on designers who pay scant attention to sustainability, inequality and other pressing social issues. In short,

it is a j’accuse against design’s darker aspects.

Marjanne van Helvert, The Responsible Object: A History of Design Ideology for the Future

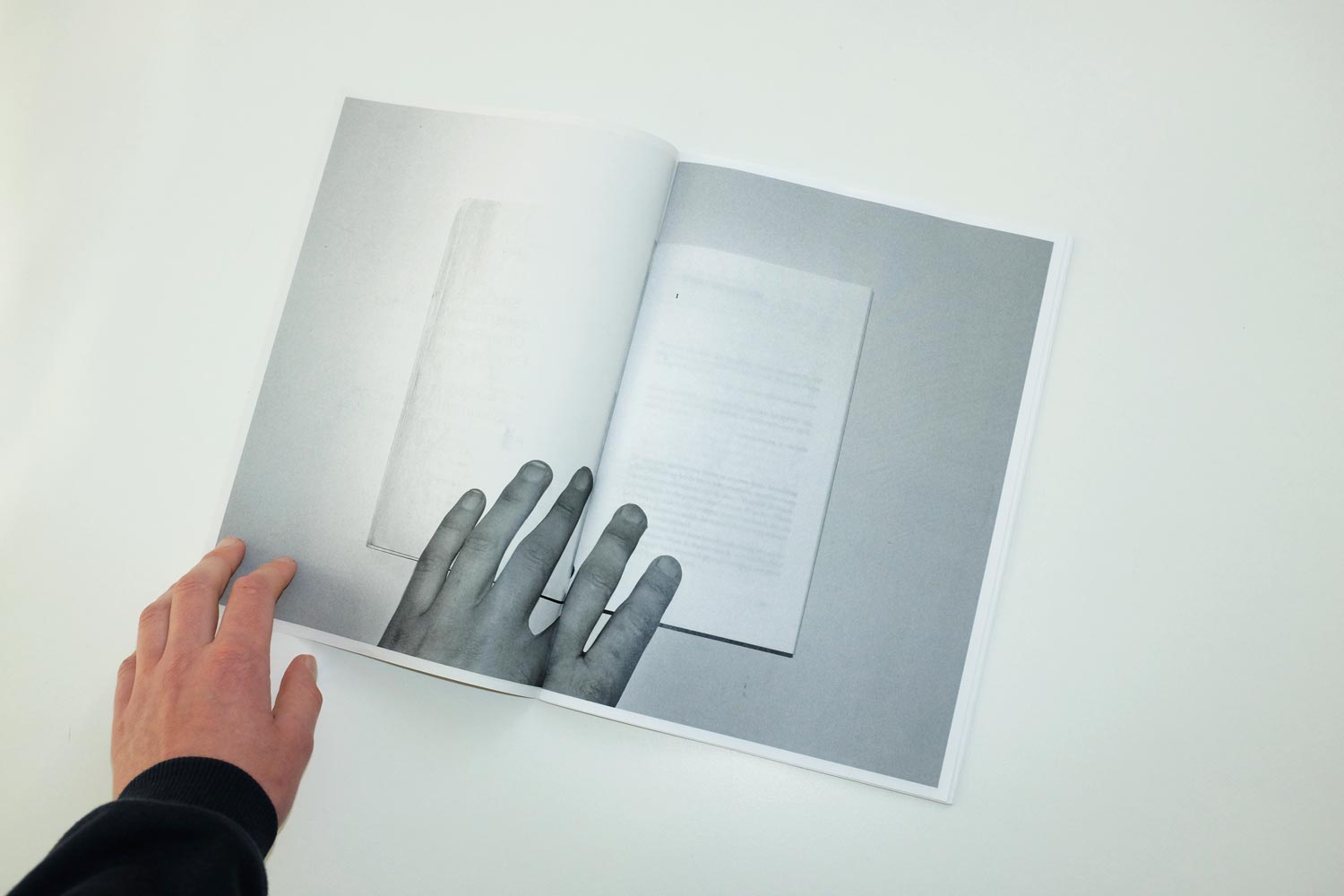

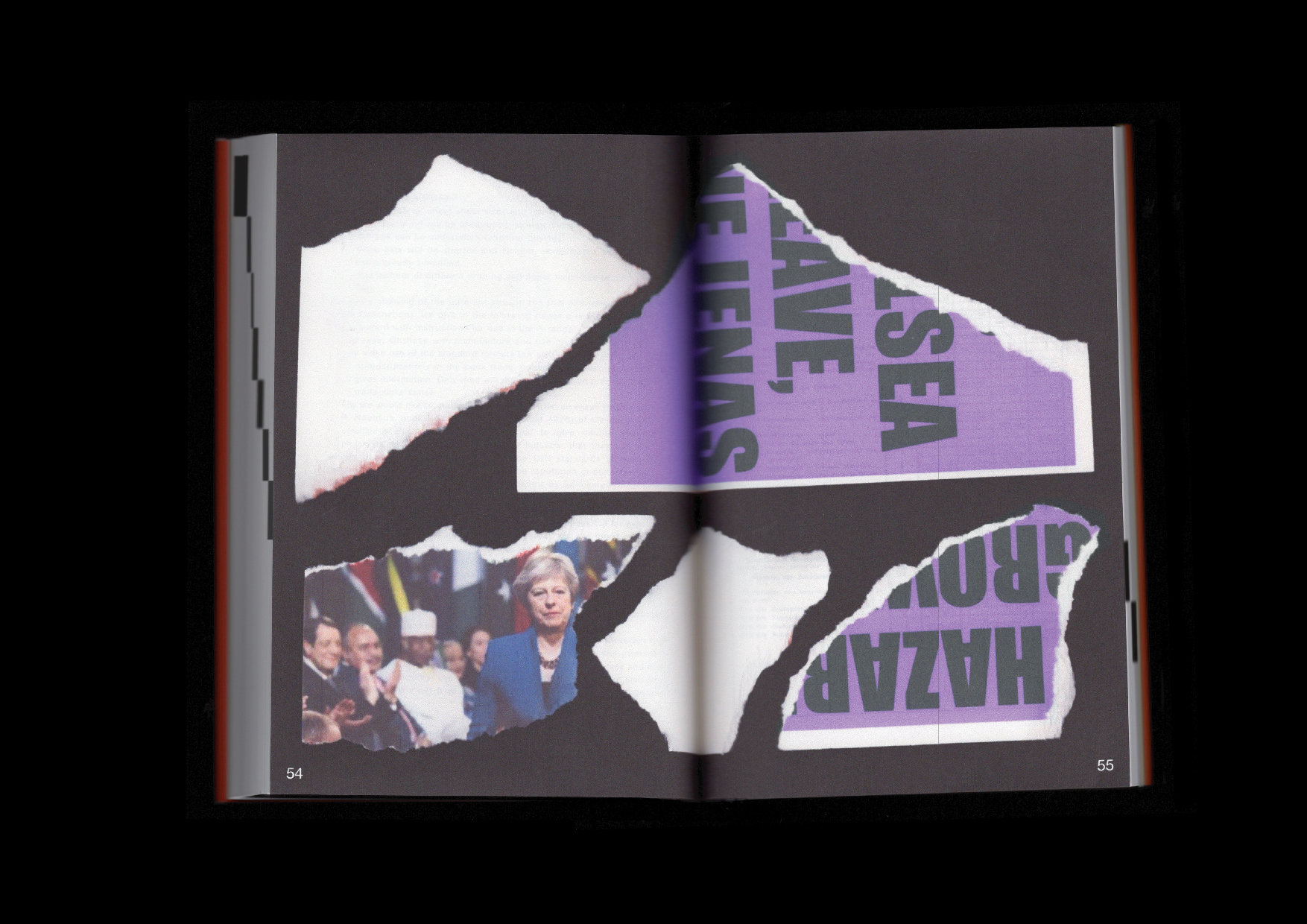

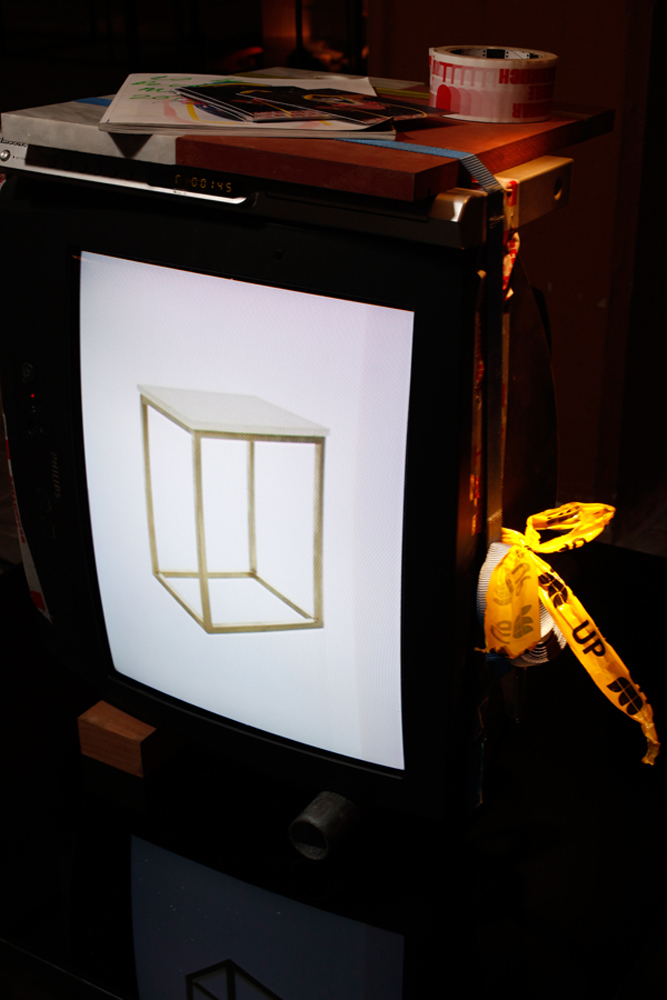

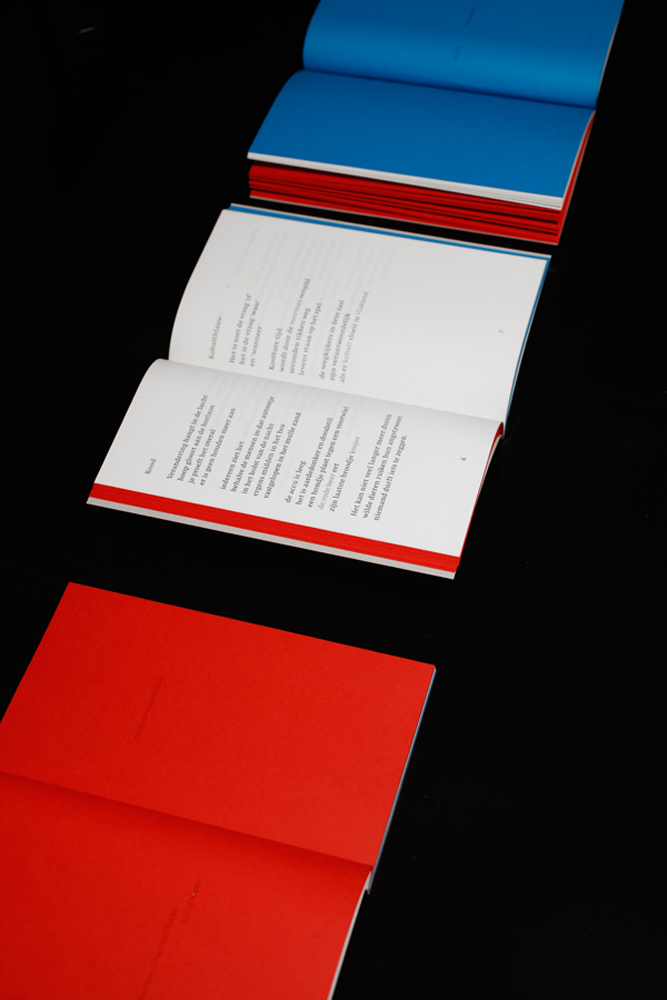

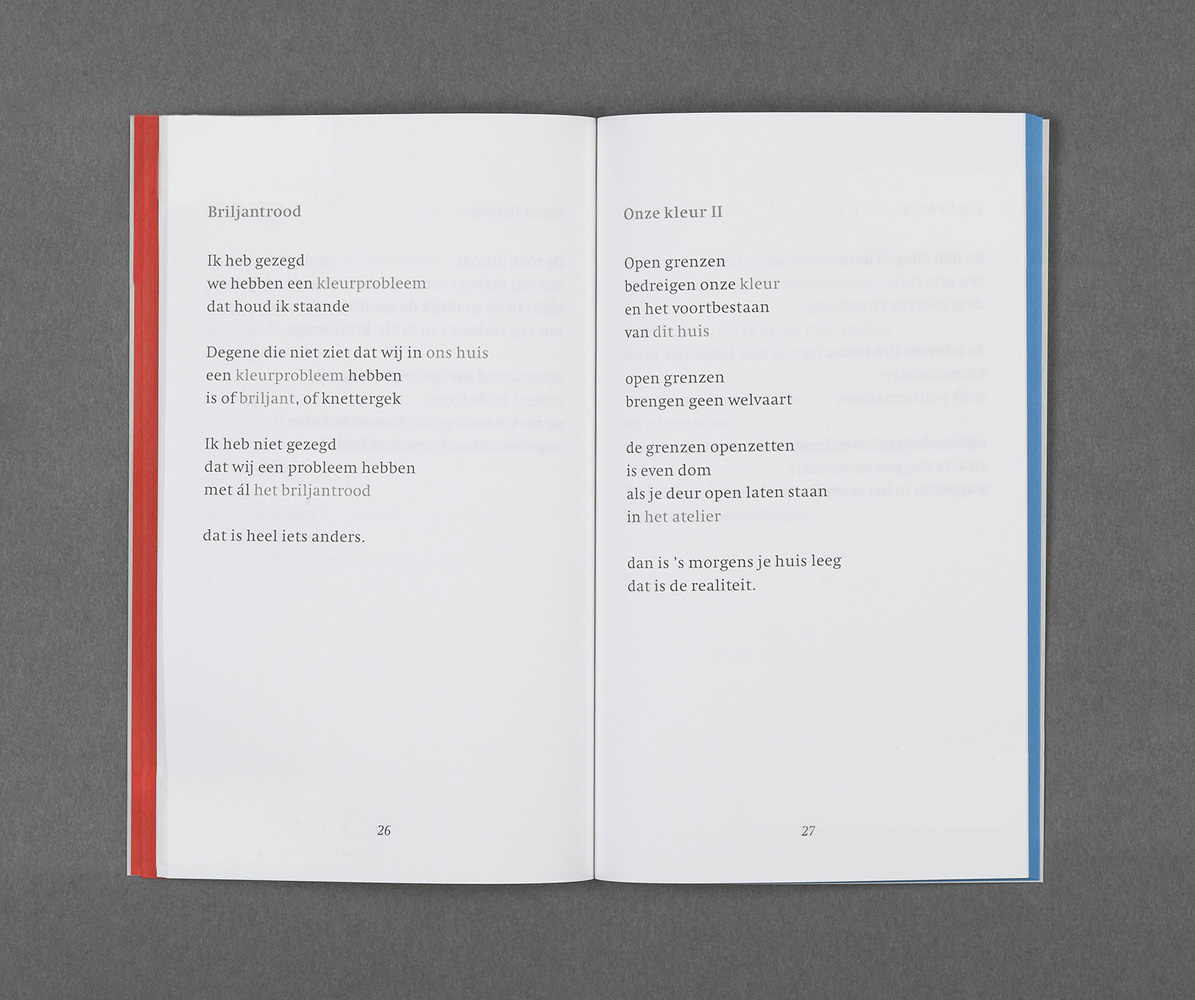

As well as being a critic, Van Helvert is also a textile designer and developed Dirty Clothes, a unisex collection of used clothing. In 2016, to further

advance her critical vision, she received a talent development grant from the Creative Industries Fund NL. They award this €25,000 subsidy annually to about

30 young designers. Van Helvert used the support to write The Responsible Object: A History of Design Ideology for the Future, in which she thoroughly

examines various design philosophies, testing them for durability and applicability now and in the near future. Unsurprisingly, the book was convincing in design

alone, executed in a clean grid and a powerful black, white and orange palette. In addition, Van Helvert’s writing demonstrates she is an astute thinker and

conscientious researcher.

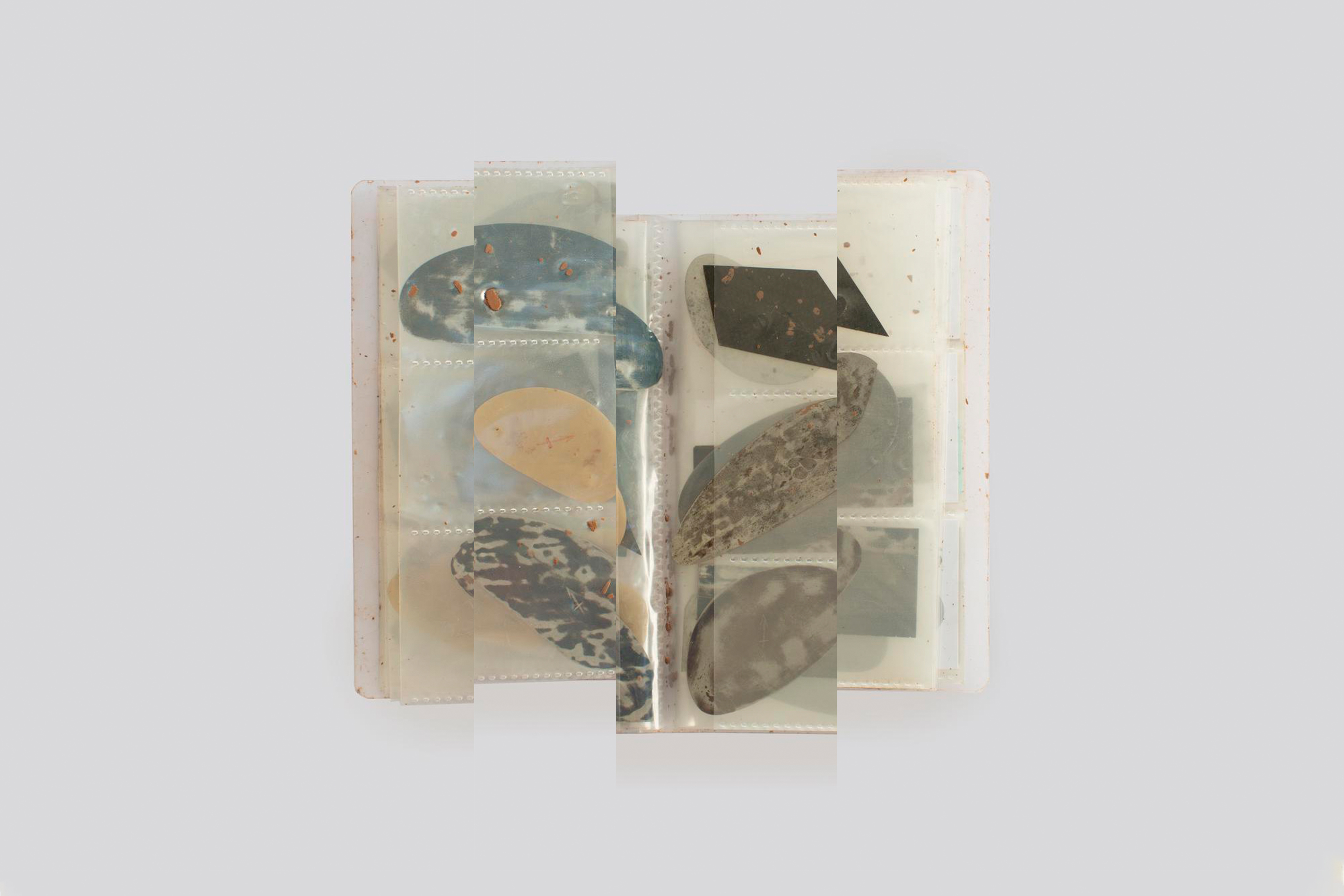

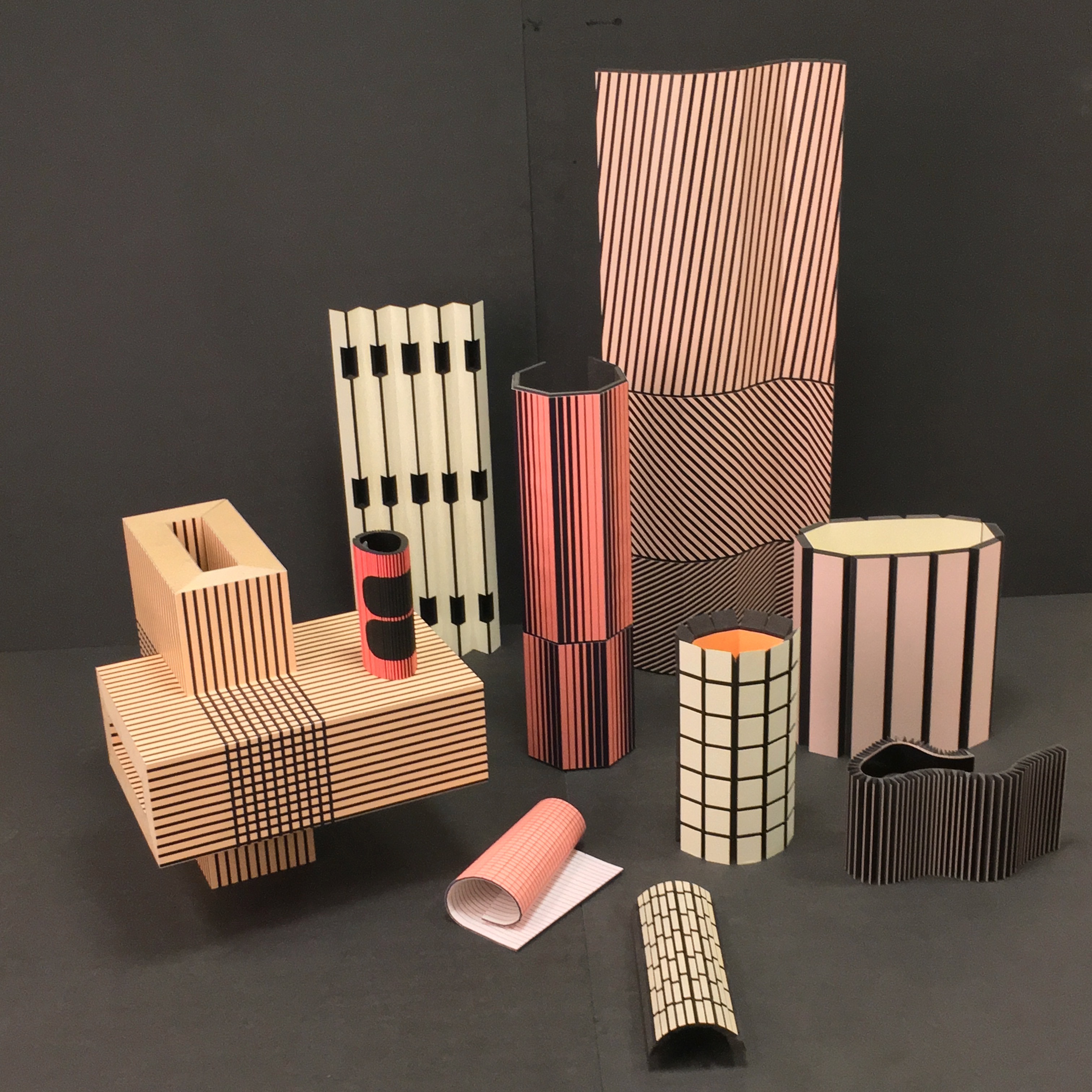

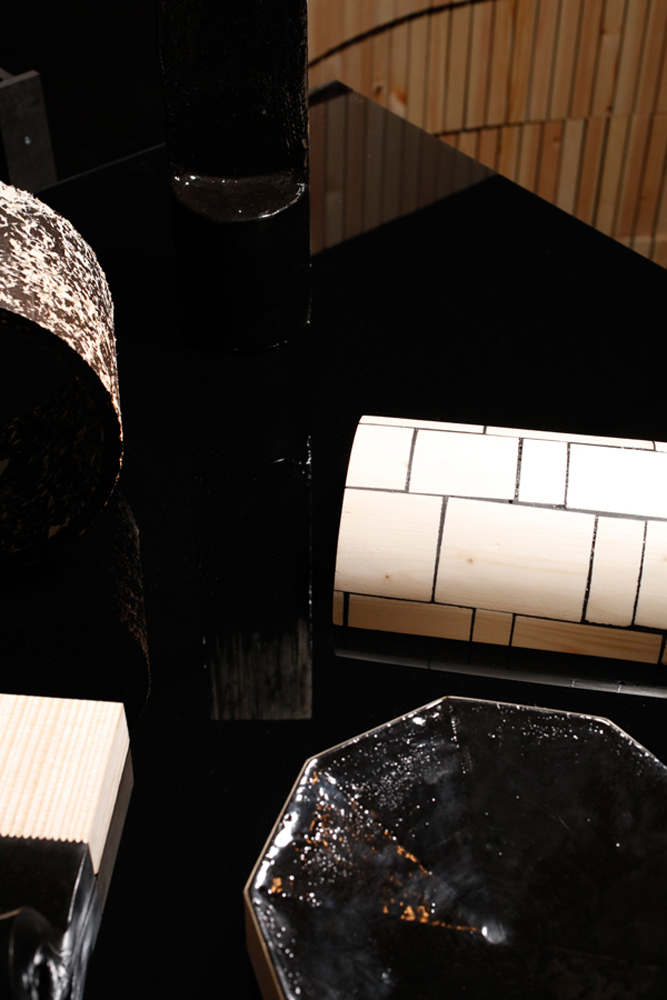

Sabine Marcelis, a library of materials

HEALING WAR WOUNDS

Van Helvert’s approach is indicative of a design generation who no longer cast their critical eye solely on their individual practice but on the entire sector.

This trend is clearly evident when we look at the various cohorts of Talent Development Scheme grant recipients over the years. Together, these design cohorts provide

a current snapshot of the creative industry.

Since the Talent Development Scheme’s launch in 2014, some 250 young designers have drawn on this opportunity to professionalise. In the first few years, the

participants mainly focused on an in-depth reflection of their own practice – with great success, in fact. For example, product designer Sabine Marcelis (2016 cohort) used her development year to collaborate with manufacturing professionals, resulting in a library of new, pure materials for various projects. It

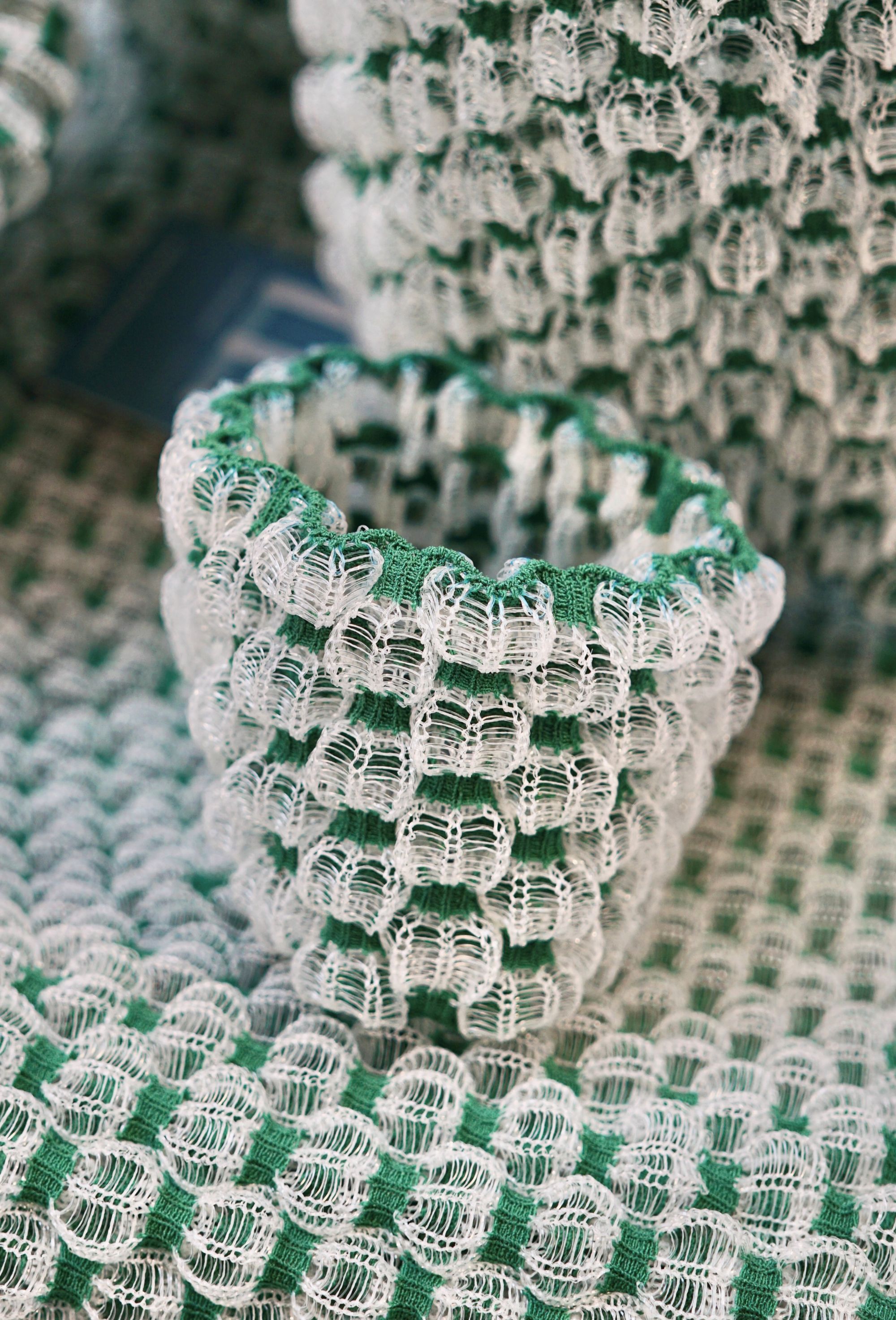

brought her world fame. Fashion designer Barbara Langedijk and jewellery designer Noon Passama (2015 cohort) experimented on Silver Fur,

a joint project with a high-tech, fur-like textile. It resulted in an innovative collection that organically merged clothing and jewellery. Or architect Arna Mačkić (2014 cohort), who examined architecture’s role in healing war wounds in her native Bosnia. In 2019, Mačkić won the Young Maaskant Prize, the highly prestigious

award for young architects. All these talented practitioners broadened their particular fascinations and strengthened their design skills to develop a unique profile.

This remains the basis of the Talent Development Scheme – the name says it all.

Gradually, alongside the recipients expanding their professional boundaries, they increasingly began to explore the precise boundaries of their professional field.

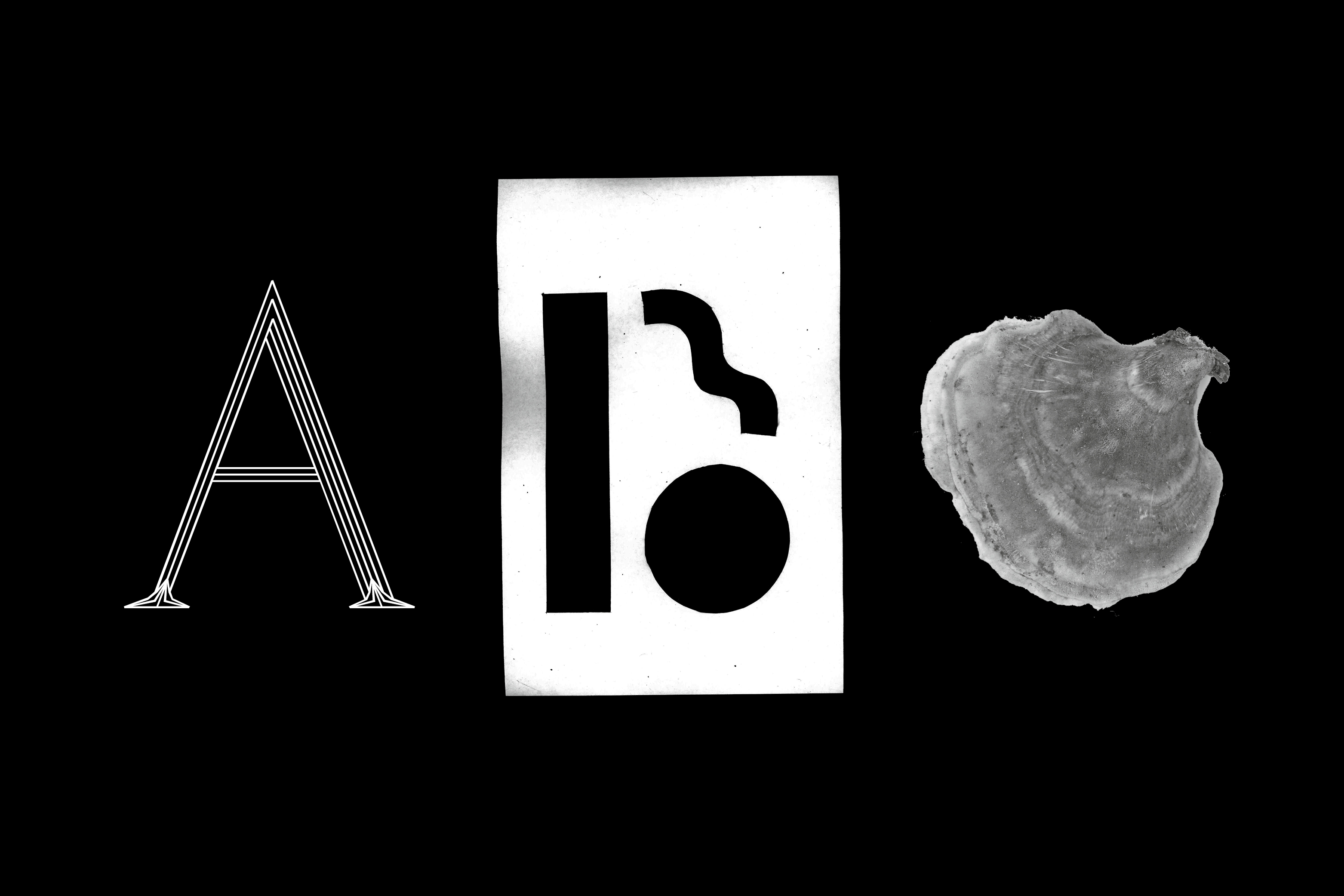

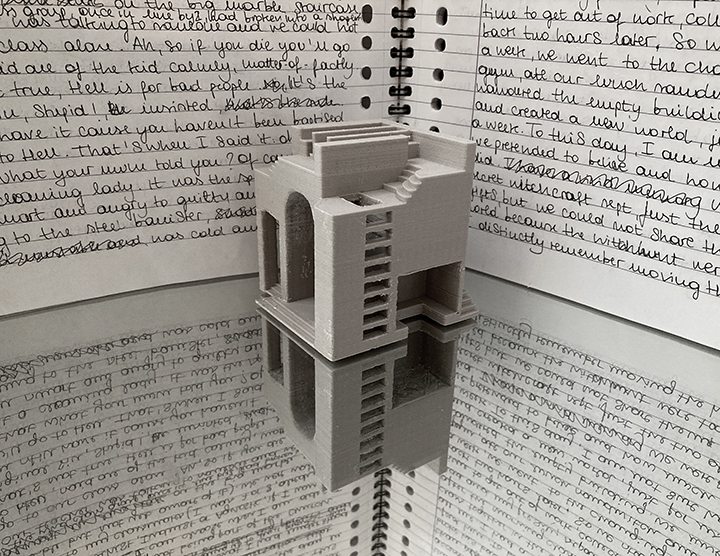

The youngest cohort also demonstrates that research is not just a means to arrive at a design. Research has become design, and this is as true in fashion as it

is in product design, graphic design, architecture, and gaming, interactive and other digital design. Why should an architect always design a building, an urban

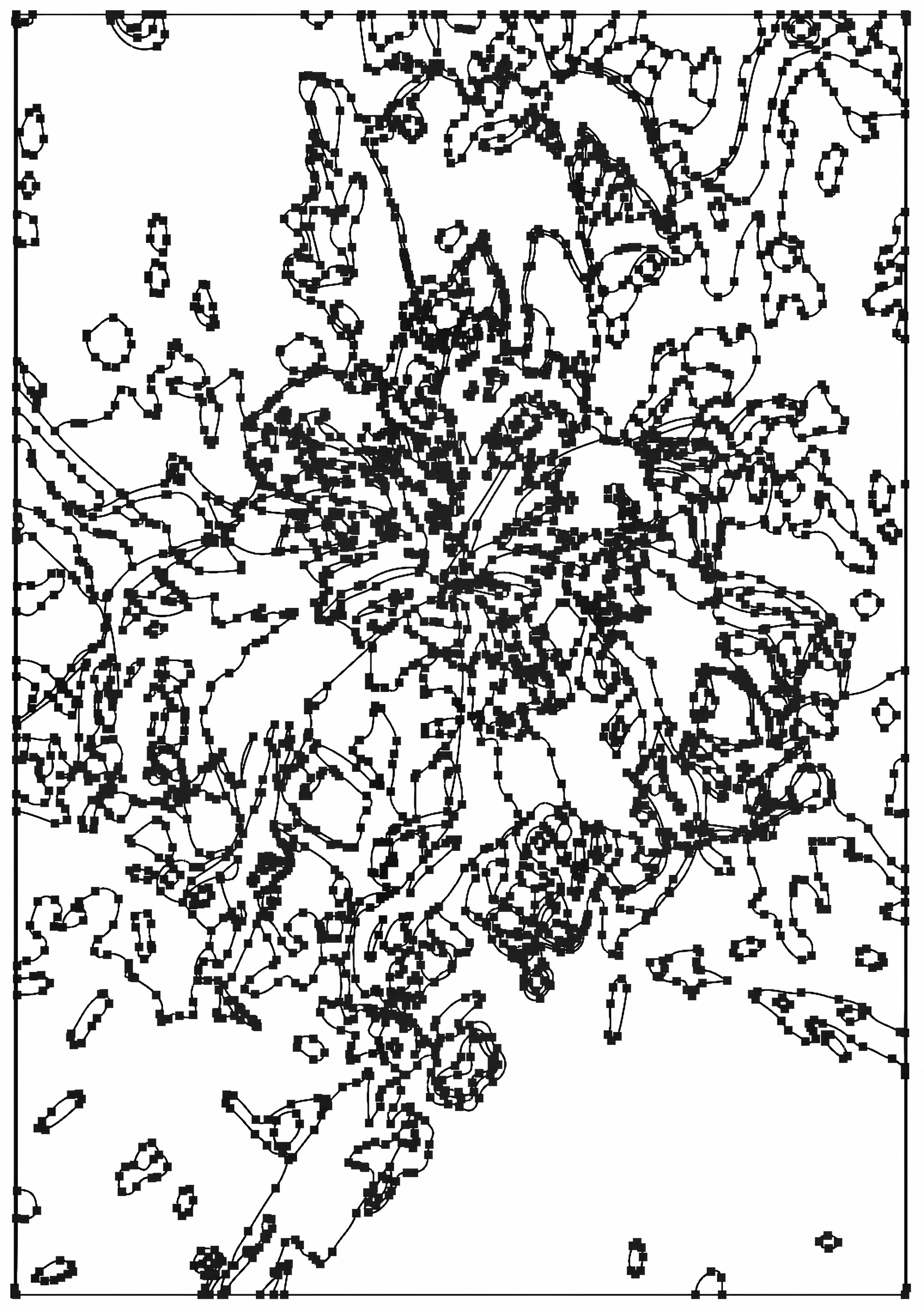

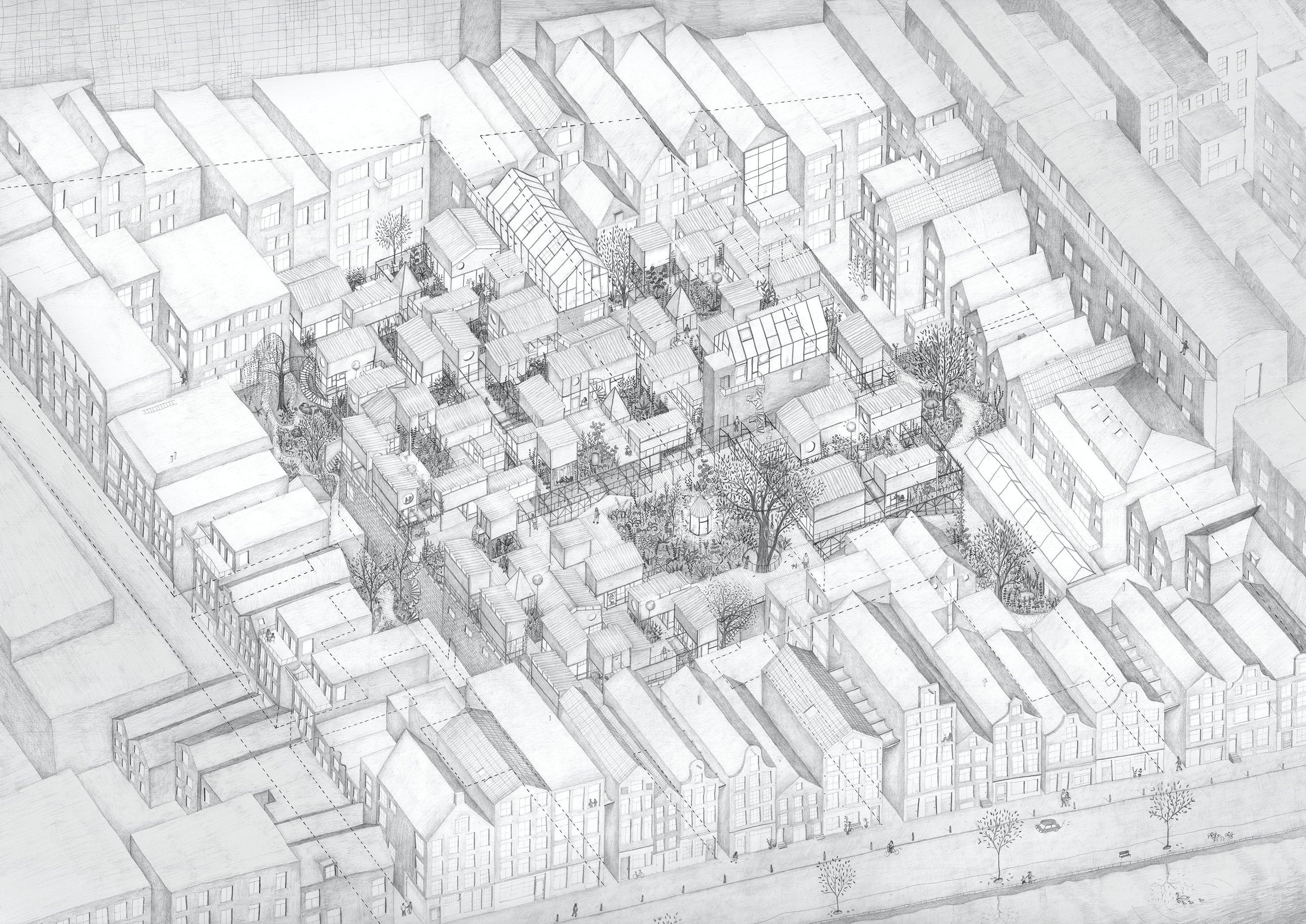

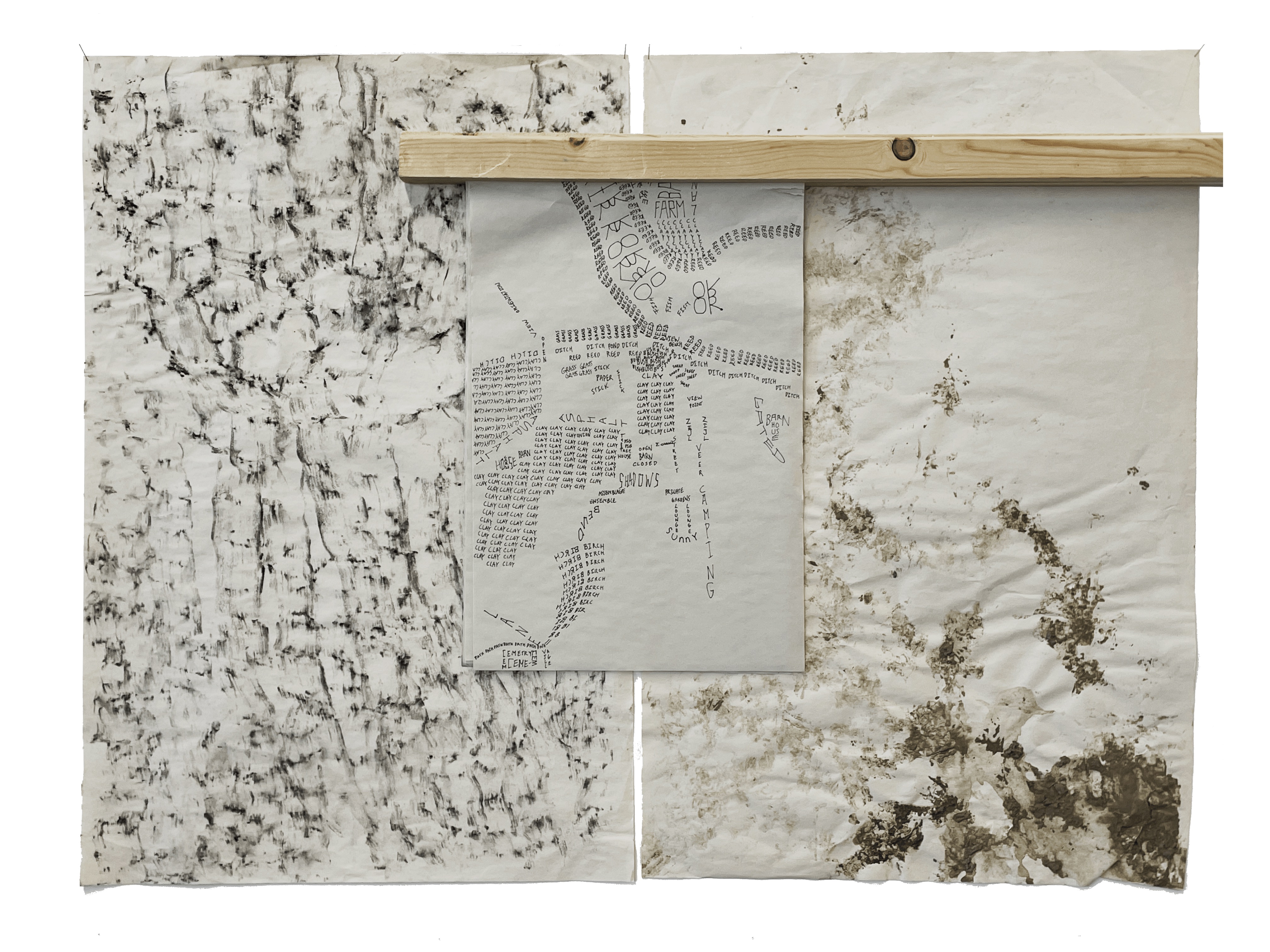

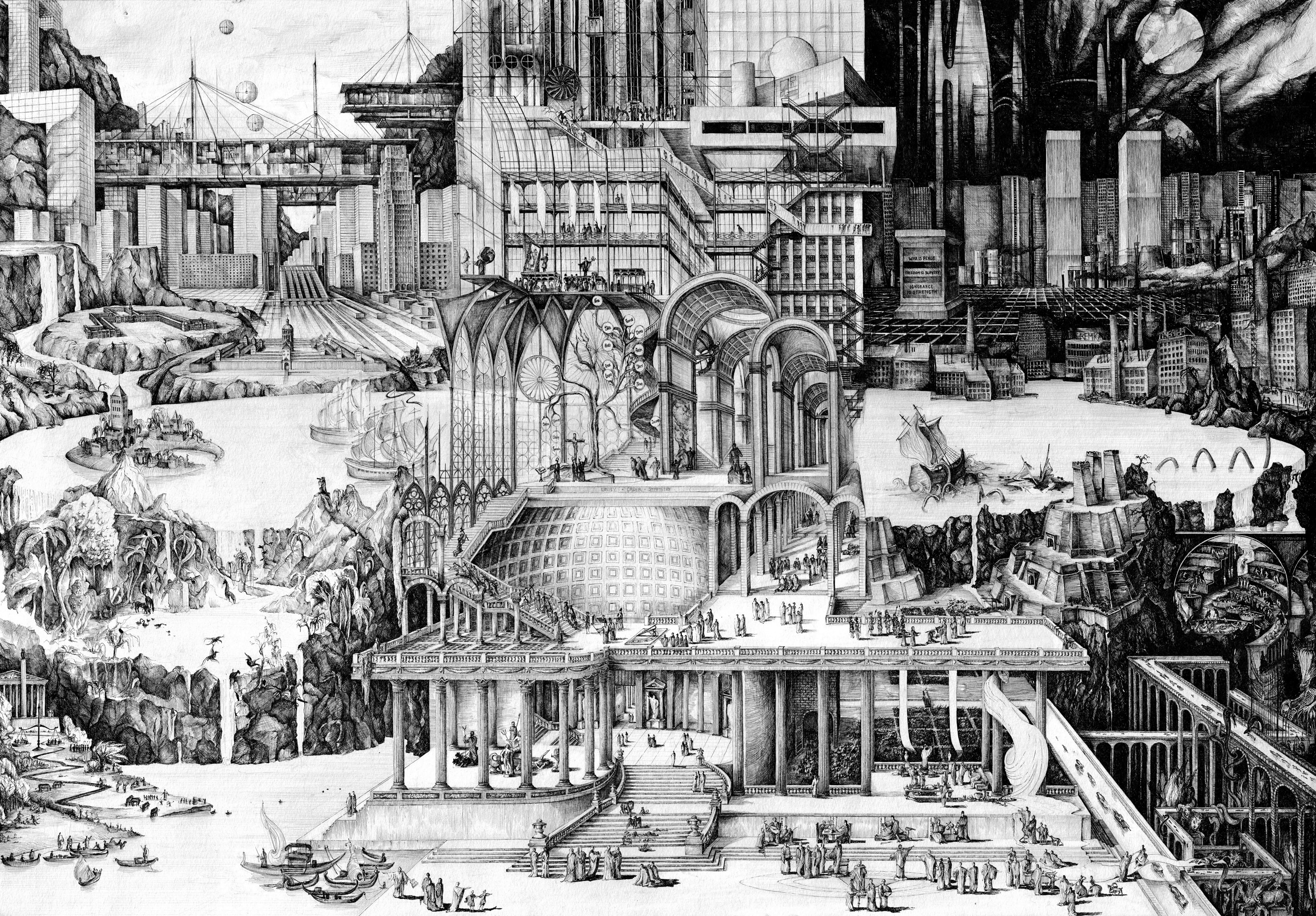

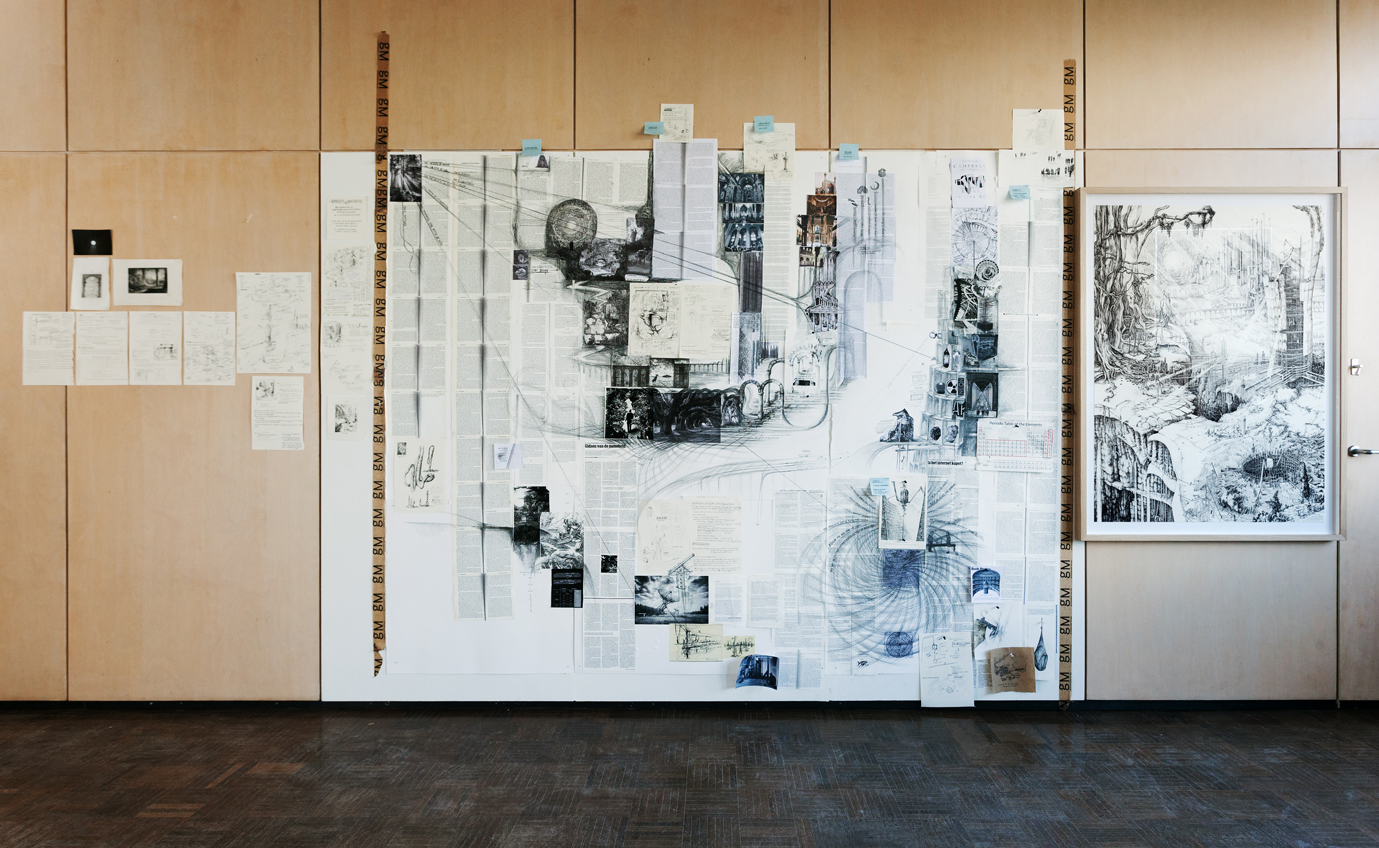

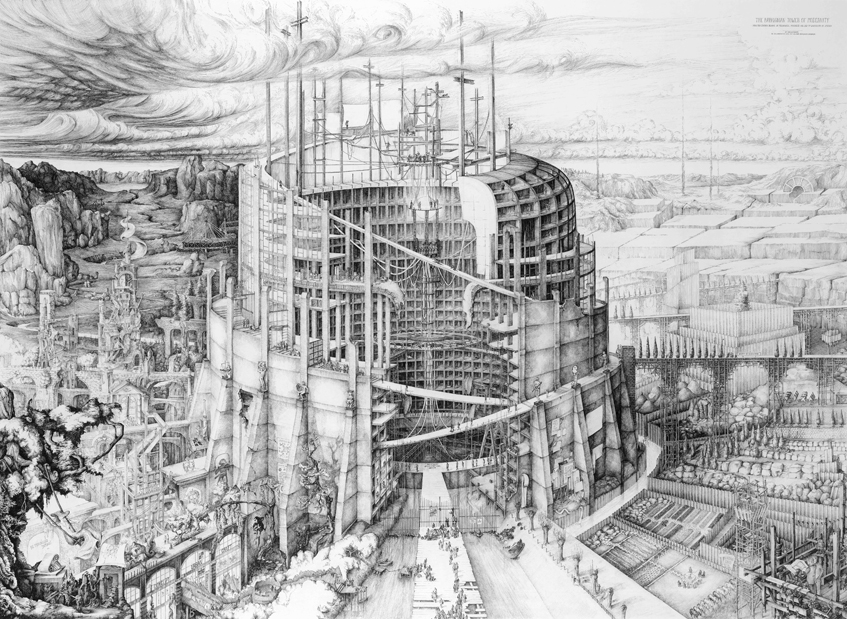

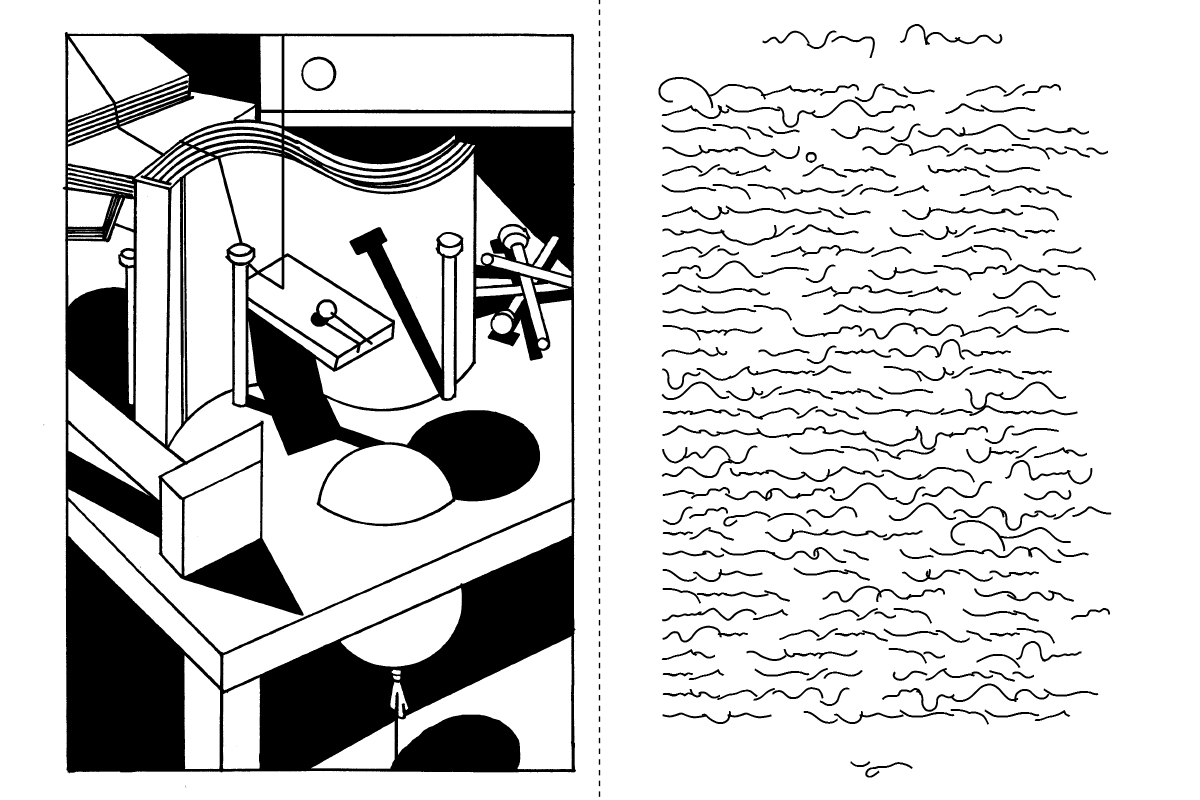

district or landscape? This is the starting point of Carlijn Kingma’s utopian landscapes (2018 cohort). Her architecture only exists on paper

and is made of nothing but jet-black ink. The meticulously detailed pen drawings are often more than a metre high and wide and consist of buildings that are part

fantasy and partly historical. These maps depict abstract and complex social concepts architecture has grappled with for centuries – utopia, capitalism and

even fear and hope. Kingma infuses her field with philosophical reflections and historical awareness. By eschewing the term architect and instead calling herself

a ‘cartographer of worlds of thought’, she positions herself beyond architecture. Like Marjanne van Helvert, she is simultaneously a participant and

observer of her profession.

Carlijn Kingma, A Histoty of the Utopian Tradition

TECH-FOOD AS A CONVERSATION PIECE

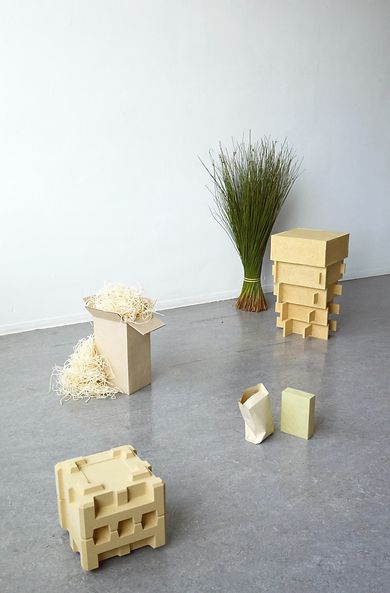

The textile designer who makes a book and the architect who does not want to build exemplifies a generation that is researching and redefining its profession. What

are the options for a fashion designer who wants to break away from the industry’s dominance? What does it mean to be a product designer in a world collapsing

under the weight of overconsumption? How do you deal with privacy issues or addictive clickbait when designing an app, website or game? Although this fundamental

self-examination is based on personal dilemmas, sometimes even frustrations, it nourishes the whole professional community.

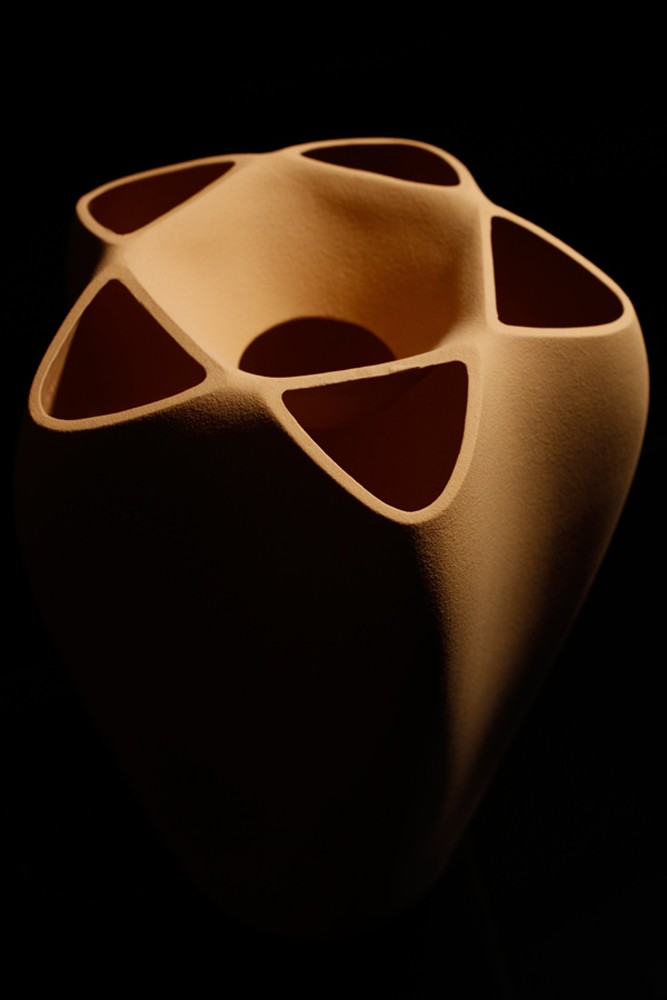

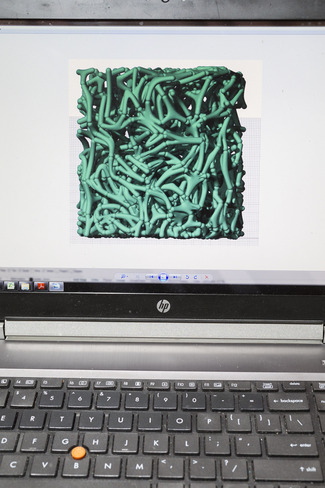

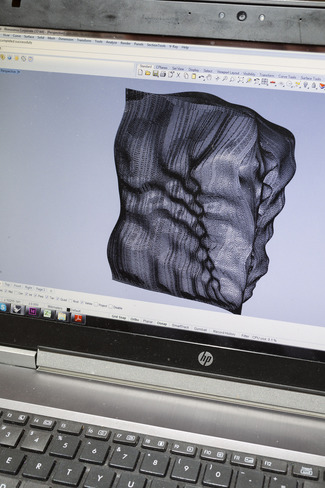

This research can be both hyper-realistic and hypothetical. Food designer Chloé Rutzerveld (2016 cohort) combines design, science, technology,

gastronomy and culture to realise projects about the food of the future. Edible Growth is a design for ready-to-eat dishes using a 3D printer. They are

made up of layers containing seeds and spores in an edible substrate. Once printed, they become an entirely edible mini garden within a few days using natural yeast

and ripening processes. Rather than an emphatically concrete product, Rutzerveld has developed a paper concept to bring discussions on social and technological

issues surrounding food to a broad audience. The resulting mediagenic images of fake dishes and intriguing project texts have resulted in Rutzerveld figuring on

the international circuit for lectures and exhibitions. Her prototype has become the product.

This probing attitude has become the unifying factor among the young designers who received a talent development grant. The goal can be a specific result, such as

creating a materials library or a fashion collection independent of seasons and gender. The entire design field is also being researched, including a manifesto

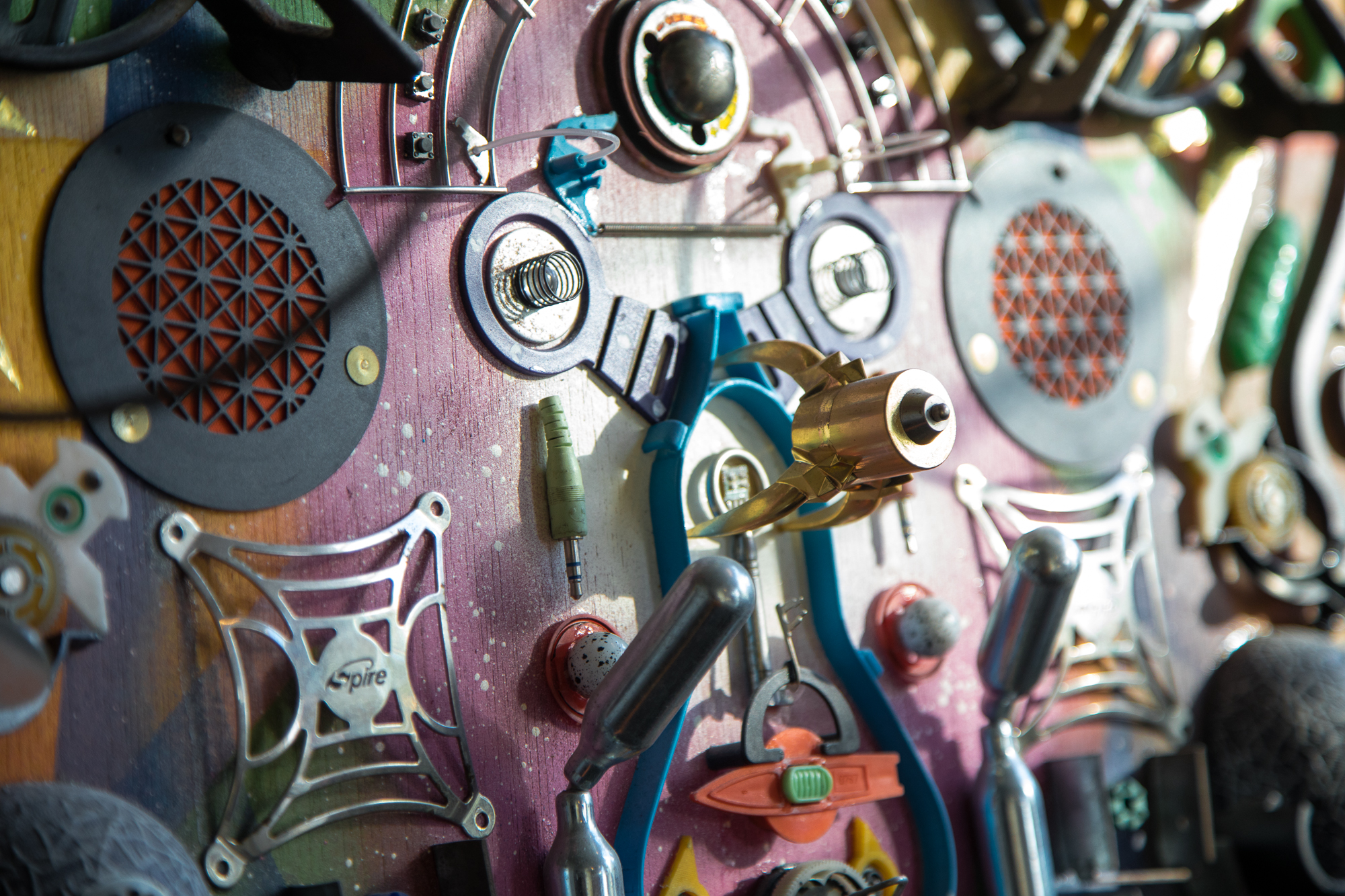

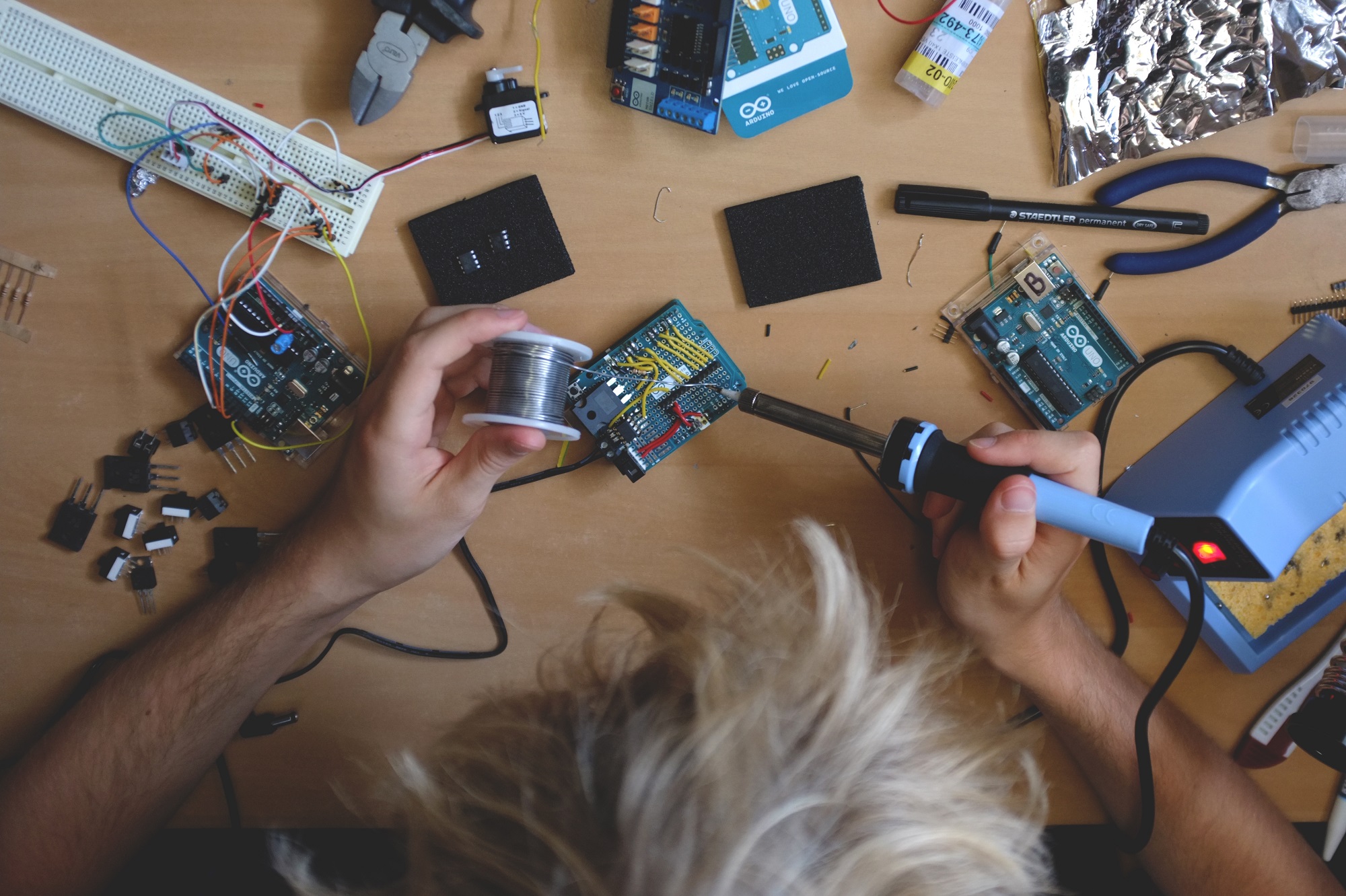

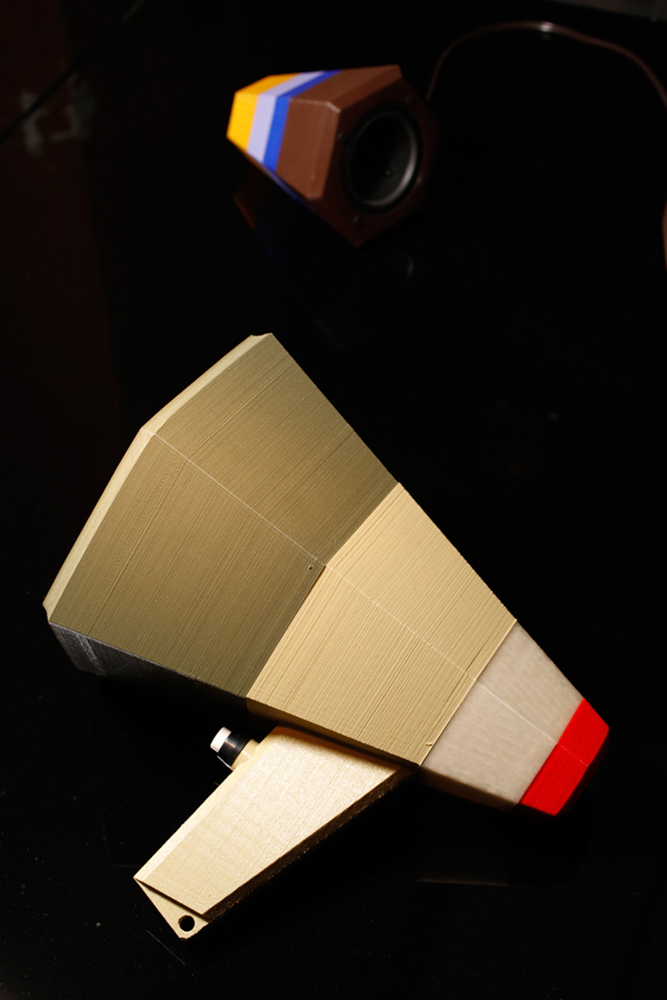

about dirty design. Another outcome is exploring the designer’s role as a producer, as Jesse Howard (2015 cohort) does with his everyday

devices that allow the user to play an active role in both the design and production process. Utilising an open-source knowledge platform, Howard explores innovative

ways to use digital fabrication tools, such as 3D printers, computerised laser cutters, and milling machines. He designs simple household appliances, such as a

kettle or vacuum cleaner, that consumers can fabricate using bolts, copper pipes and other standard materials from the hardware store. Specific parts, such as the

protective cover, can be made with a 3D printer. They share the required techniques on the knowledge platform. If the device is defective, the producing consumer

– or prosumer – can also repair it. These DIY products are made from local materials and offer a sustainable and transparent alternative to mass production.

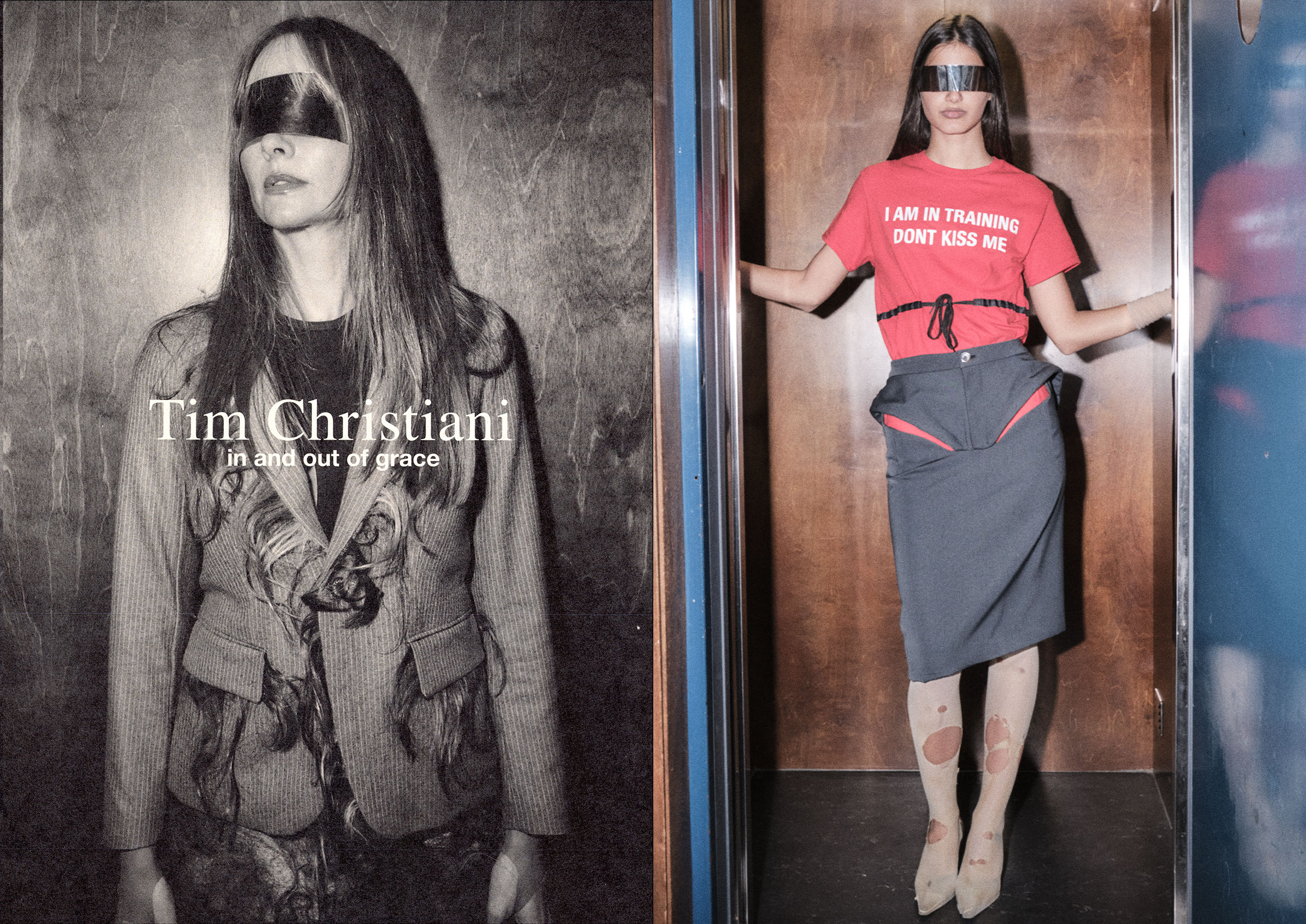

PERFORMER, DJ, CHOREOGRAPHER – AND DESIGNER

During the past seven years of the Talent Development Scheme, design’s boundaries have been interrogated and expanded through new idioms, such as social design,

food design, conceptual design, and speculative design. Architects act as quartermasters and cartographers. Fashion disrupts with anthropological installations.

Today it is as much an inquisitive mentality as a skillset that distinguishes design talent. Sometimes the individual’s approach is such that graphic design,

architecture or fashion no longer appropriately describe their practice.

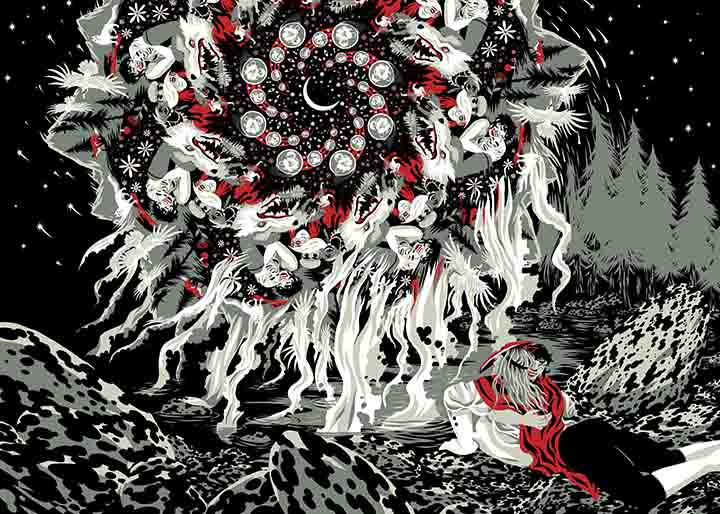

Juliette Lizotte (2020 cohort) wants to employ videos and LARP (live action role-playing, a role-playing game in which players assume a fantasy

role) to stimulate the discussion about climate change. Under the name Jujulove, she DJs, collaborates with dancers and theatre makers, and, with a fashion designer,

makes recycled plastic costumes for the dancers in her videos. In her self-appointed role as a witch, she promotes ecofeminism, in which women represent a creative

and healing force on nature. Through a multisensory experience of image, sound and performance, she mainly aims her work at young people and target groups not traditionally

considered by the cultural sector. However, her fantasy world actually runs parallel to the traditional design world. Jujulove is not a designer but creates a groundbreaking

holistic design using diverse disciplines such as film and storytelling.

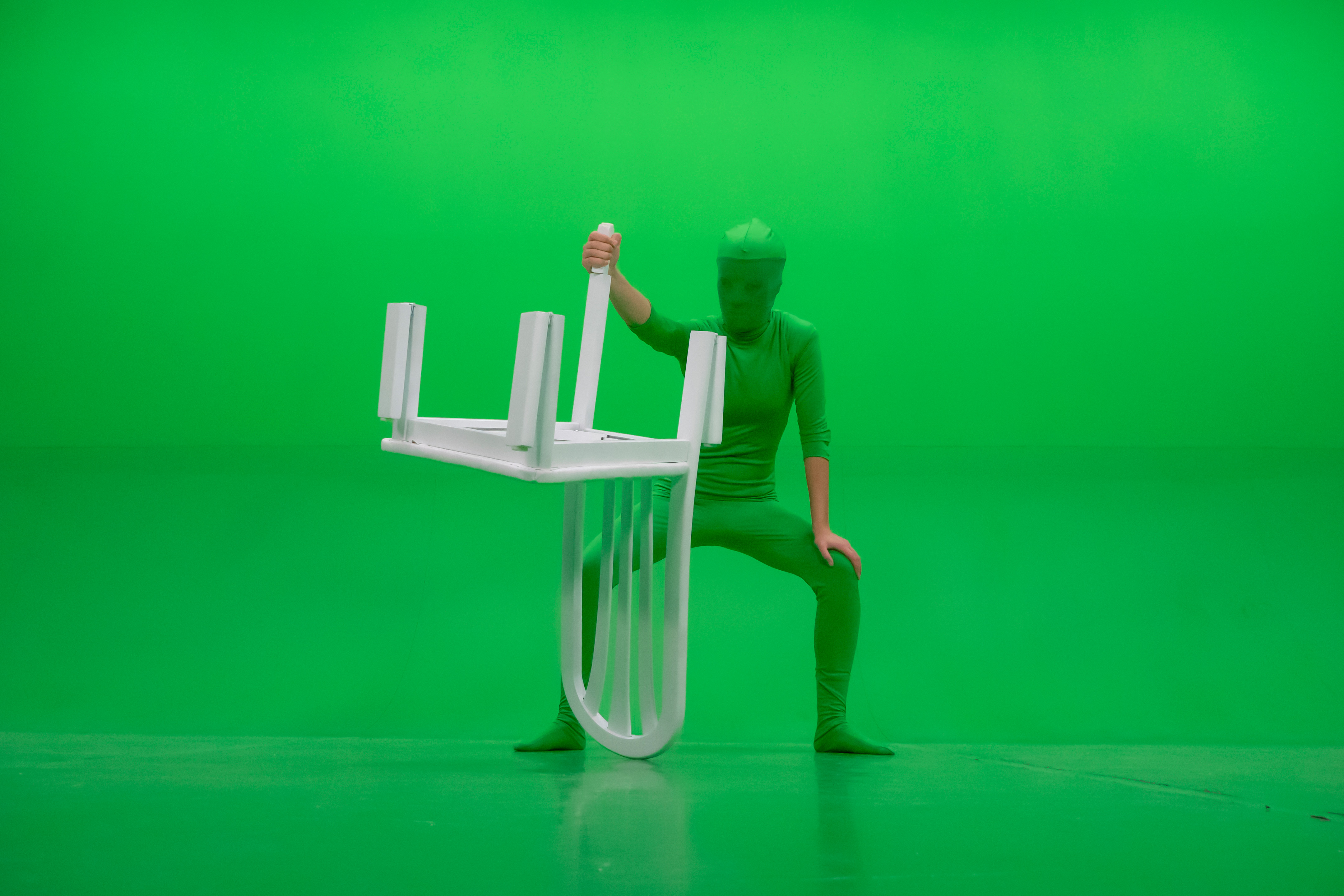

Designers are no longer central to their own design practice. There is an explicit pursuit of interdisciplinary collaboration and interaction. Though French-Caribbean

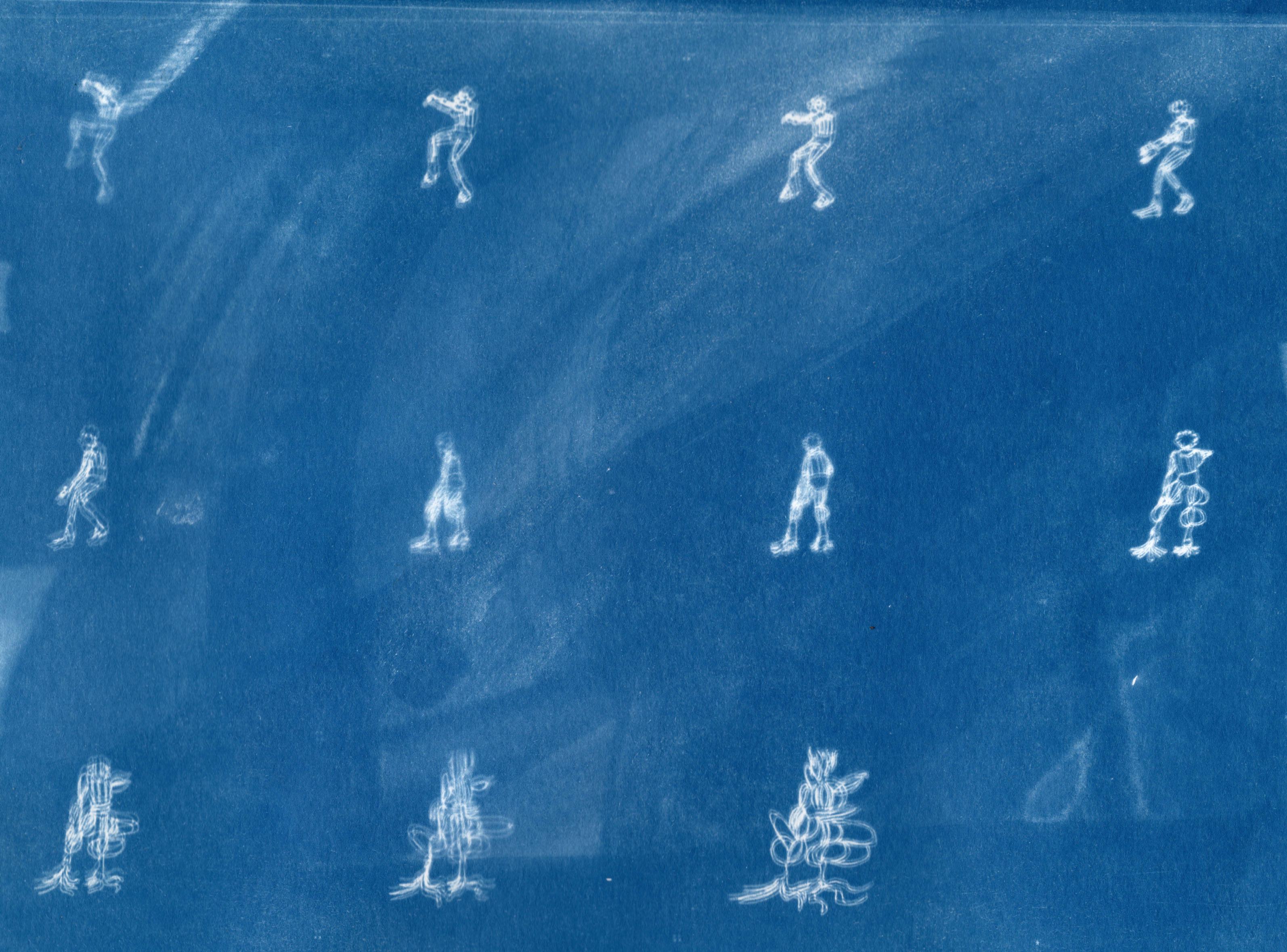

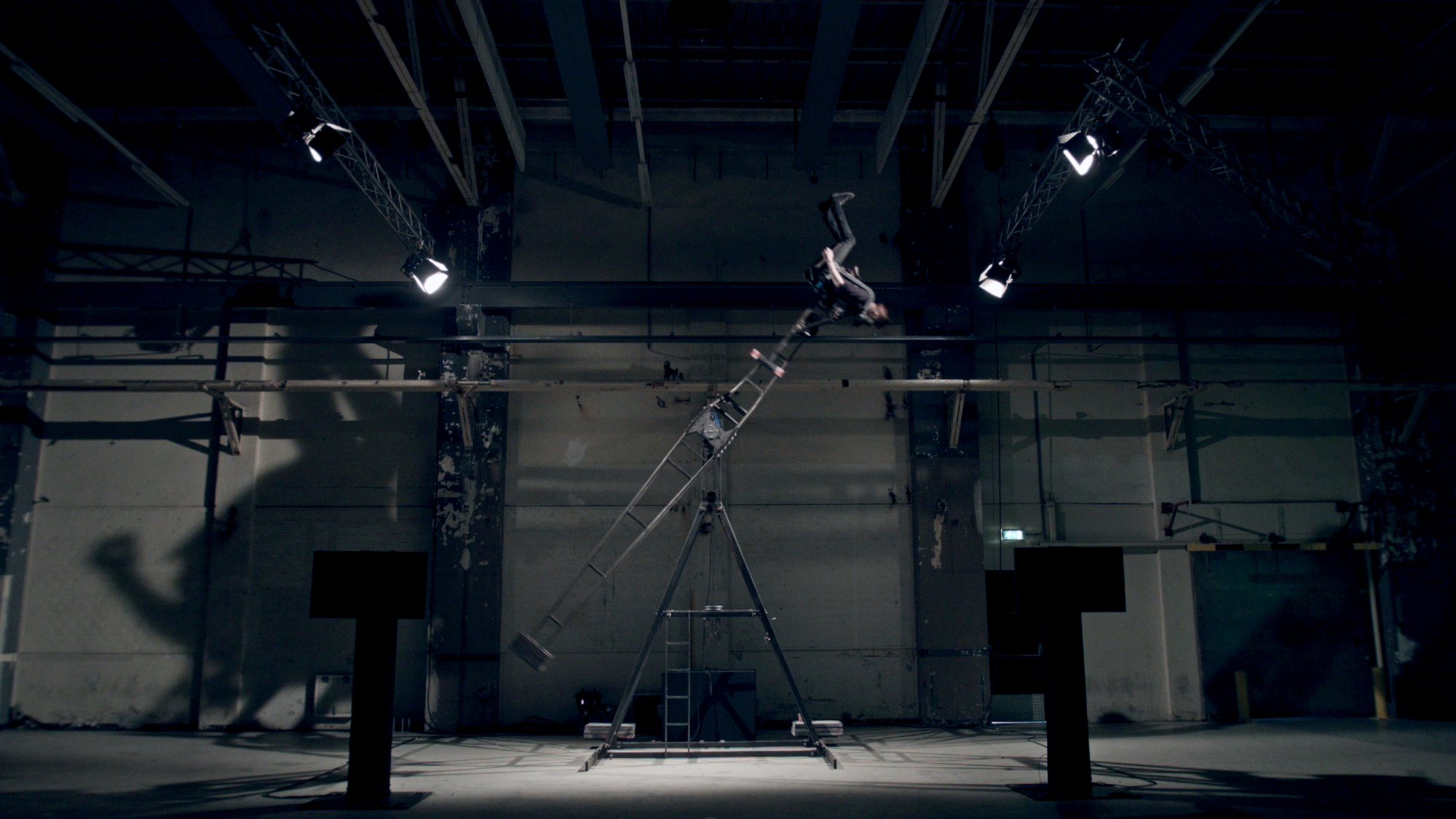

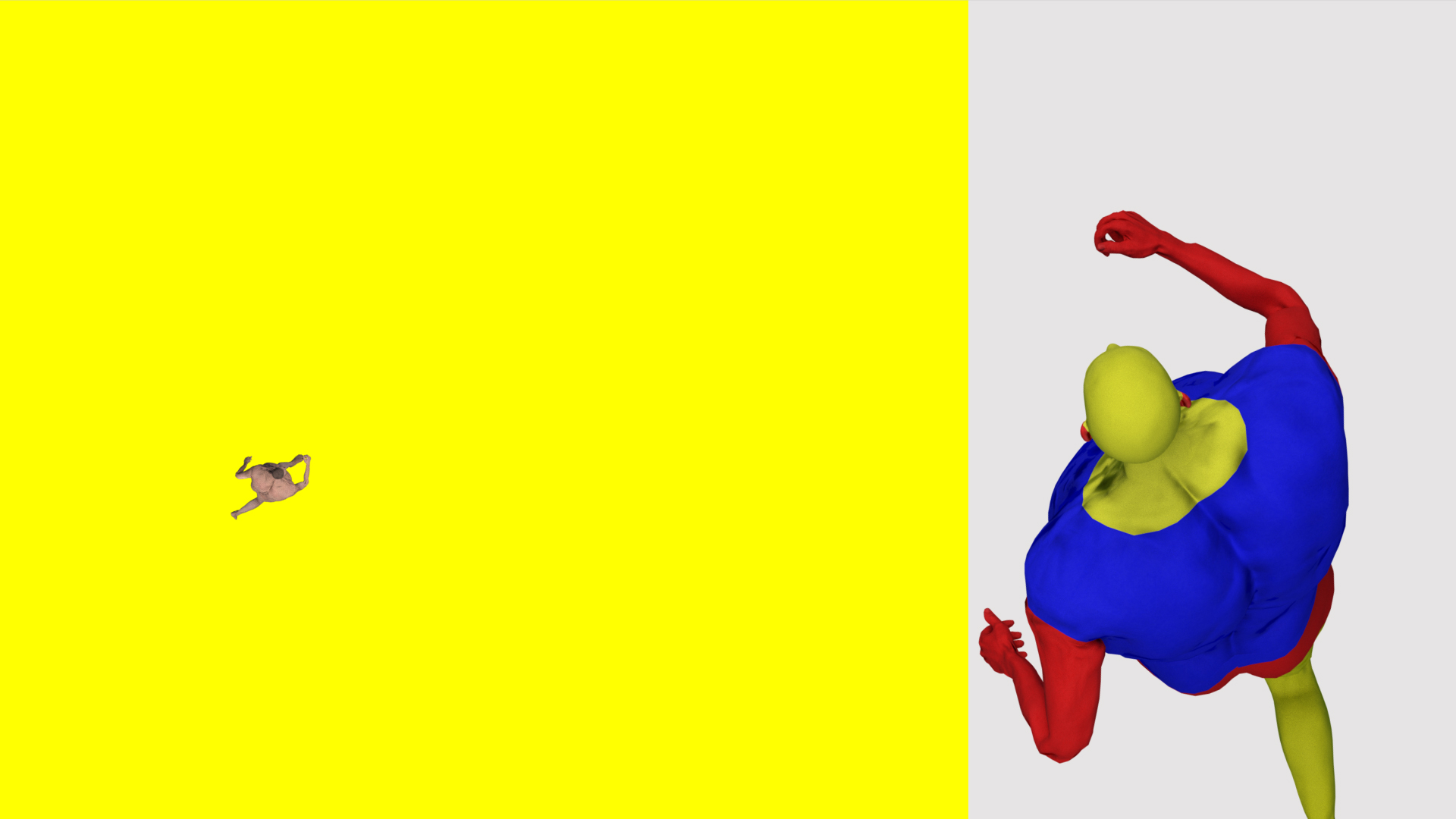

programmer/designer Alvin Arthur (2020 cohort) trained as a designer, he has developed into a versatile performer, teacher, researcher and connector.

His toolkit is his body, which he uses to visualise how the writing of computer programs works. He calls his mixture of choreography, performance and design body.coding.

Through a specially developed lesson programme, full of group dance and movement, he teaches primary school children about the extent to which their living environment

is digitally programmed, from their school buildings and places where they live to the design and production of their smartphones. Above all, he shows that programming

and design are not necessarily sedentary activities that you do behind a desk. Designing is thinking, moving, combining and collaborating.

The latter is especially true. Sometimes two different disciplines work together to great effect, such as jewellery designer Noon Passama and fashion designer Baraba

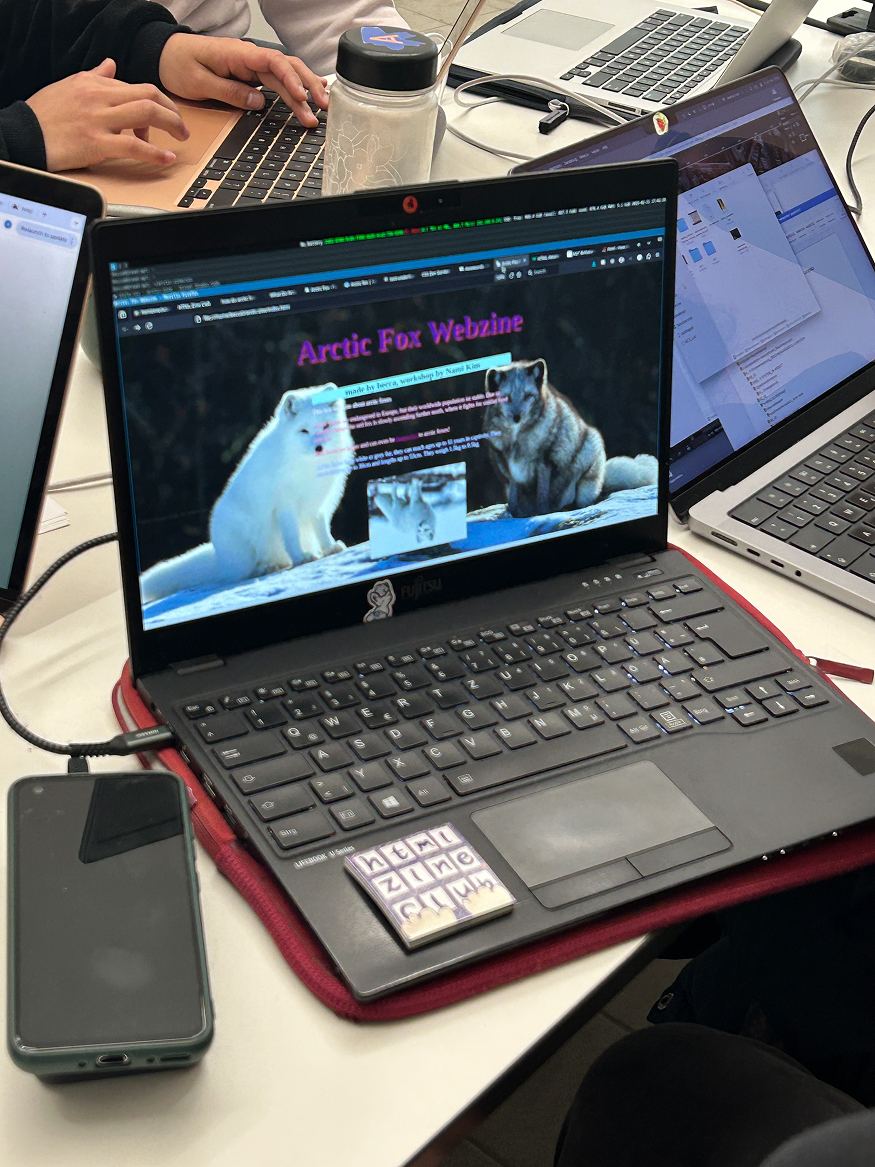

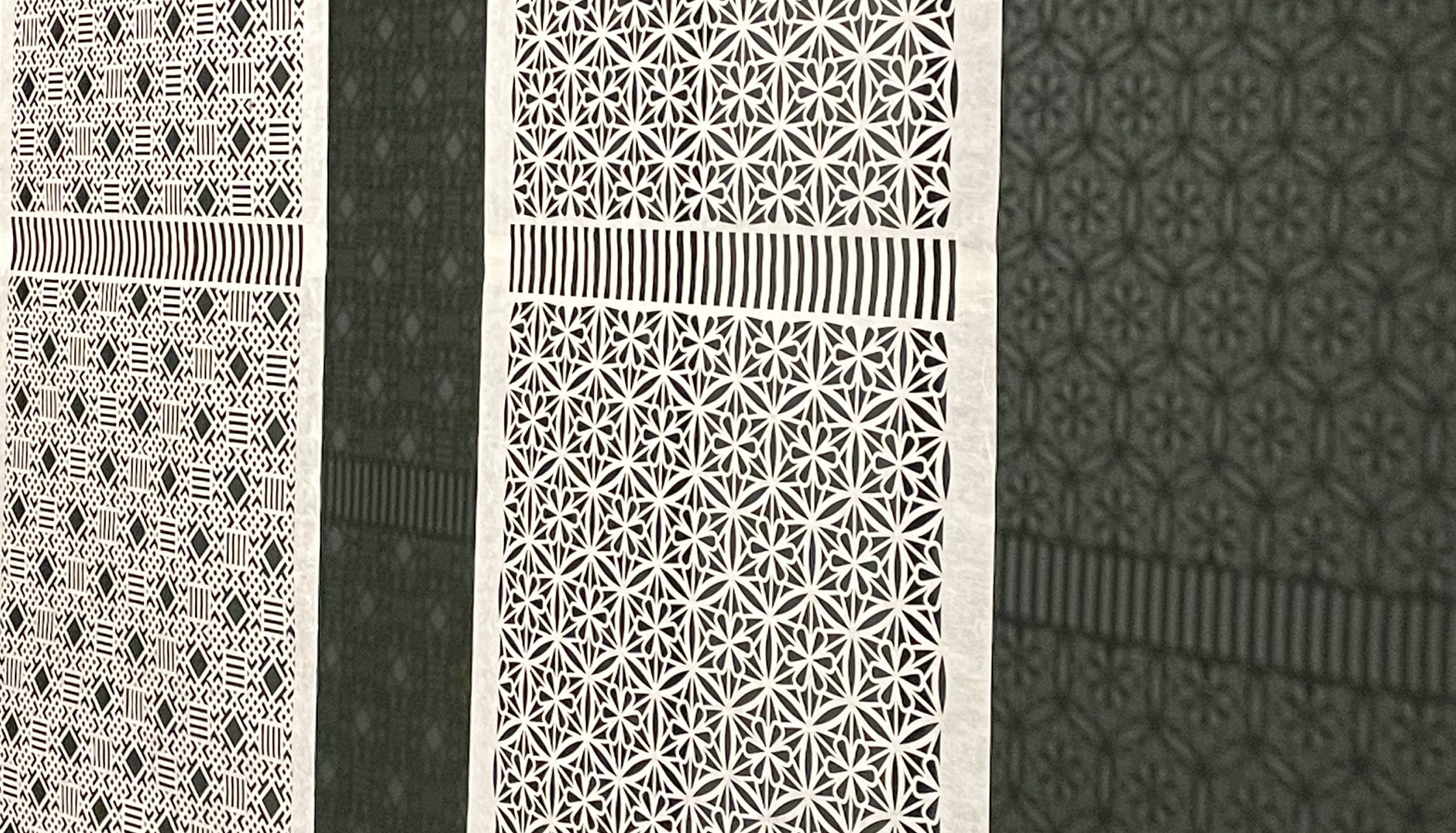

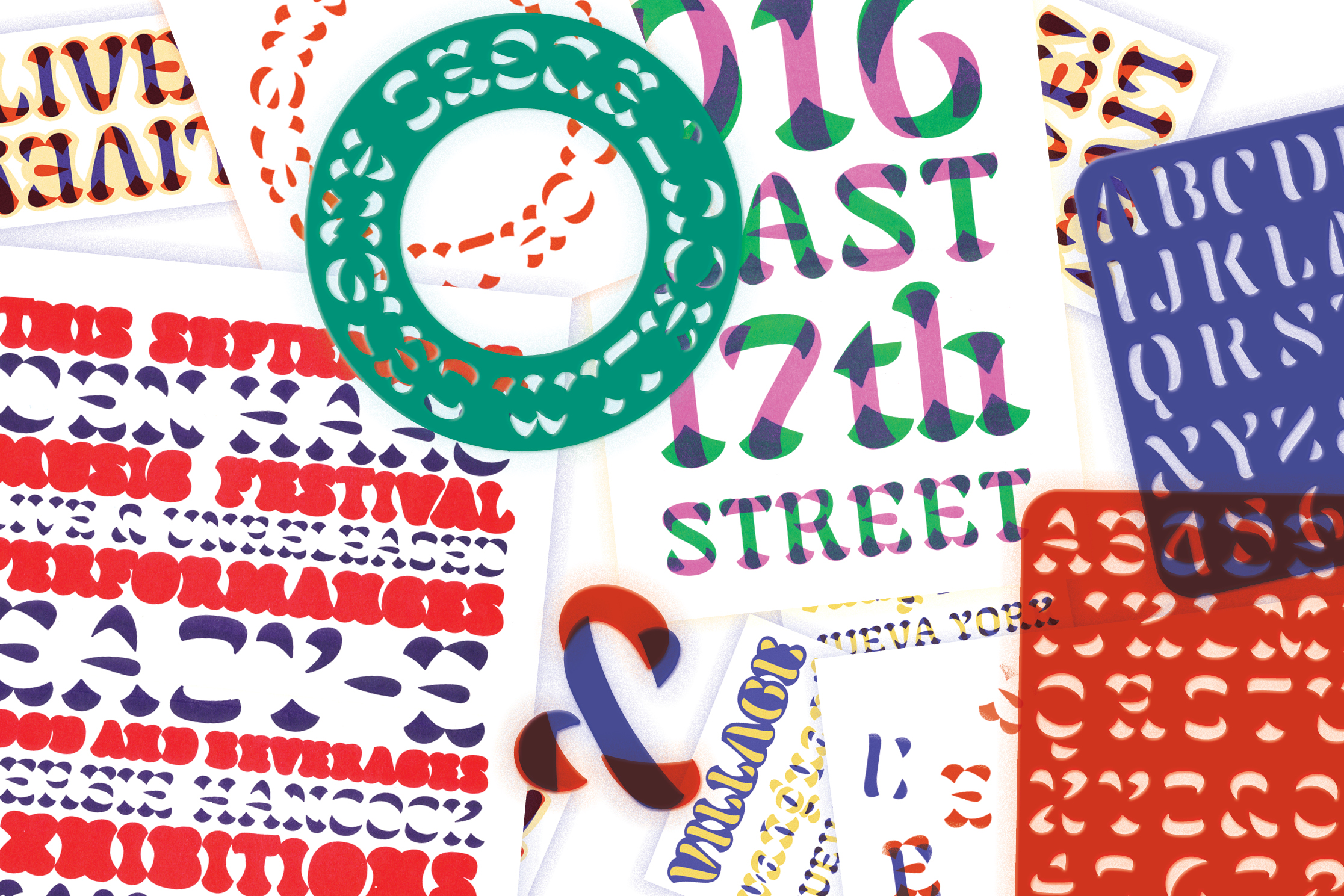

Langendijk. Increasingly, however, designers are combining their knowledge and skills in close-knit collectives. Knetterijs (2019 cohort) is a

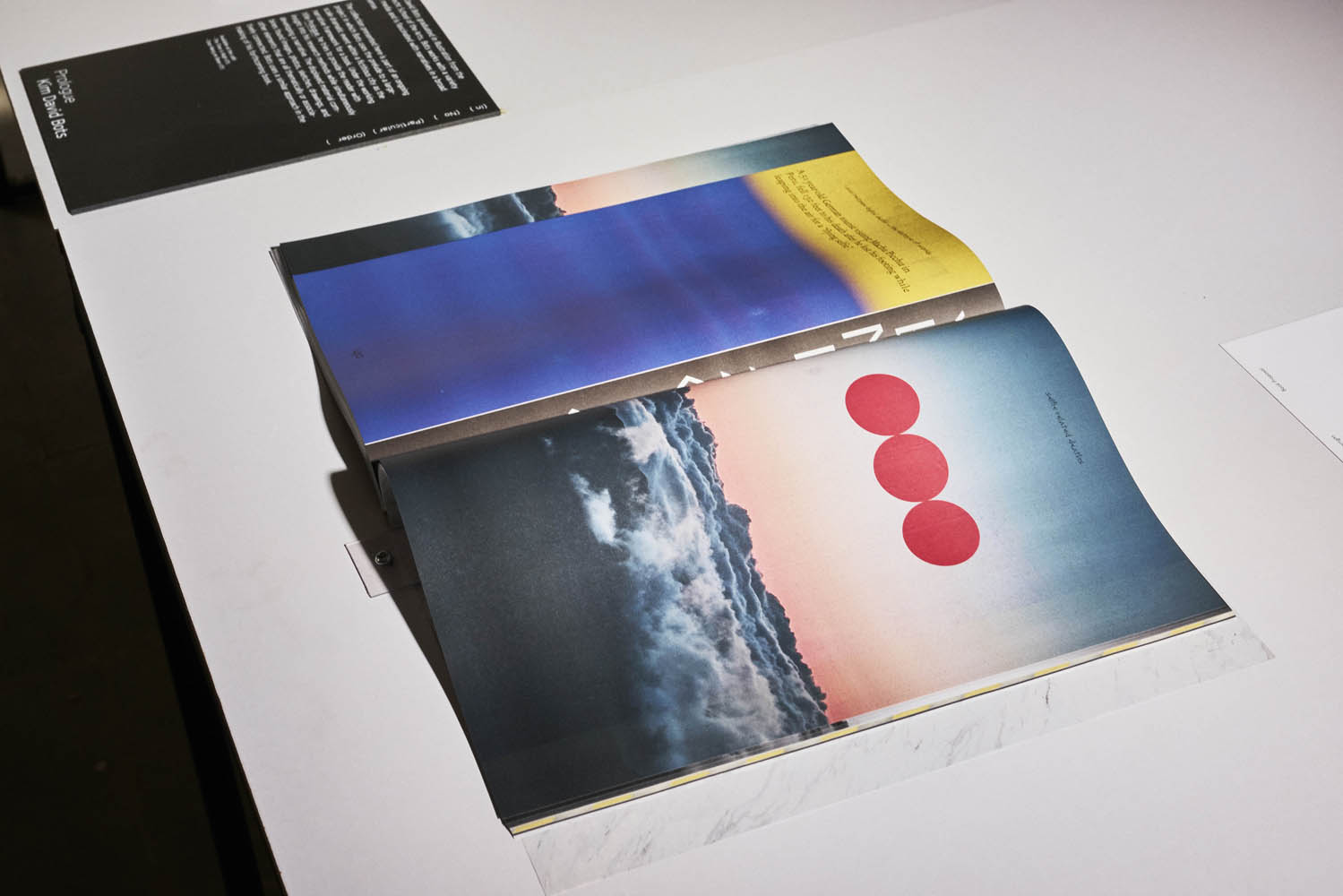

group of eight graphic designers who operate as one studio. Each member has their expertise and role, from analogue printing techniques, such as risoprint and screen

printing, to digital illustration techniques or running the Knetterijs webshop. They used their development year for the joint production of three ‘magazines’

in which new techniques such as graphic audio tracks and an interactive e-zine were explored. They replace individual ego with ‘we go’.

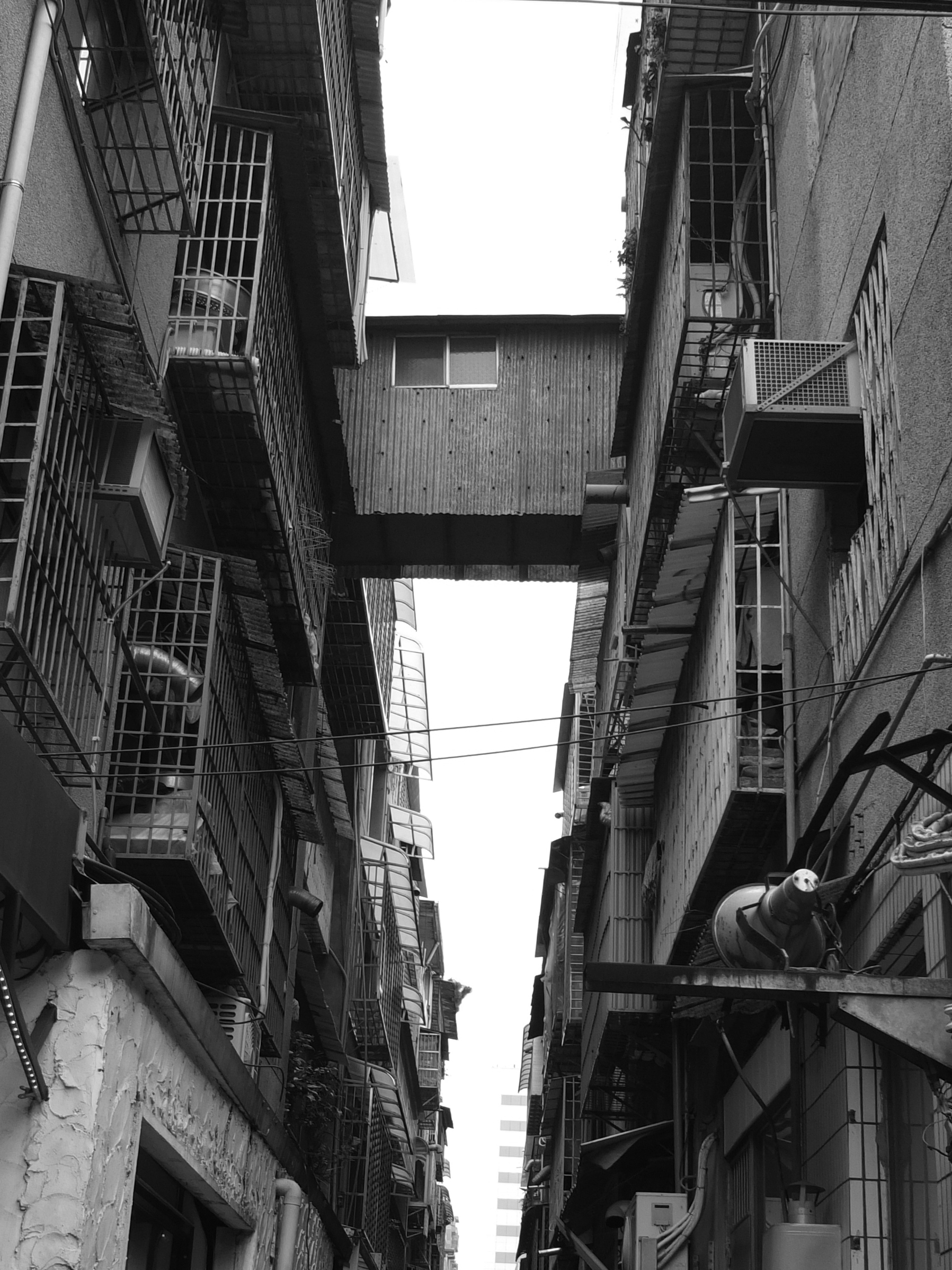

Saïd Kinos, HIDEOUT, Uruma hotel in Okinawa, Japan. Photo Masafumi Kashi

STORYTELLING AND STREET ART

This transformation of the design disciplines is now at the heart of the Talent Development Scheme. Since 2019, scout nights have offered creative talent that has

not trained on the usual courses – such as those at the Design Academy Eindhoven or TU Delft – an opportunity to pitch their work to a selection committee.

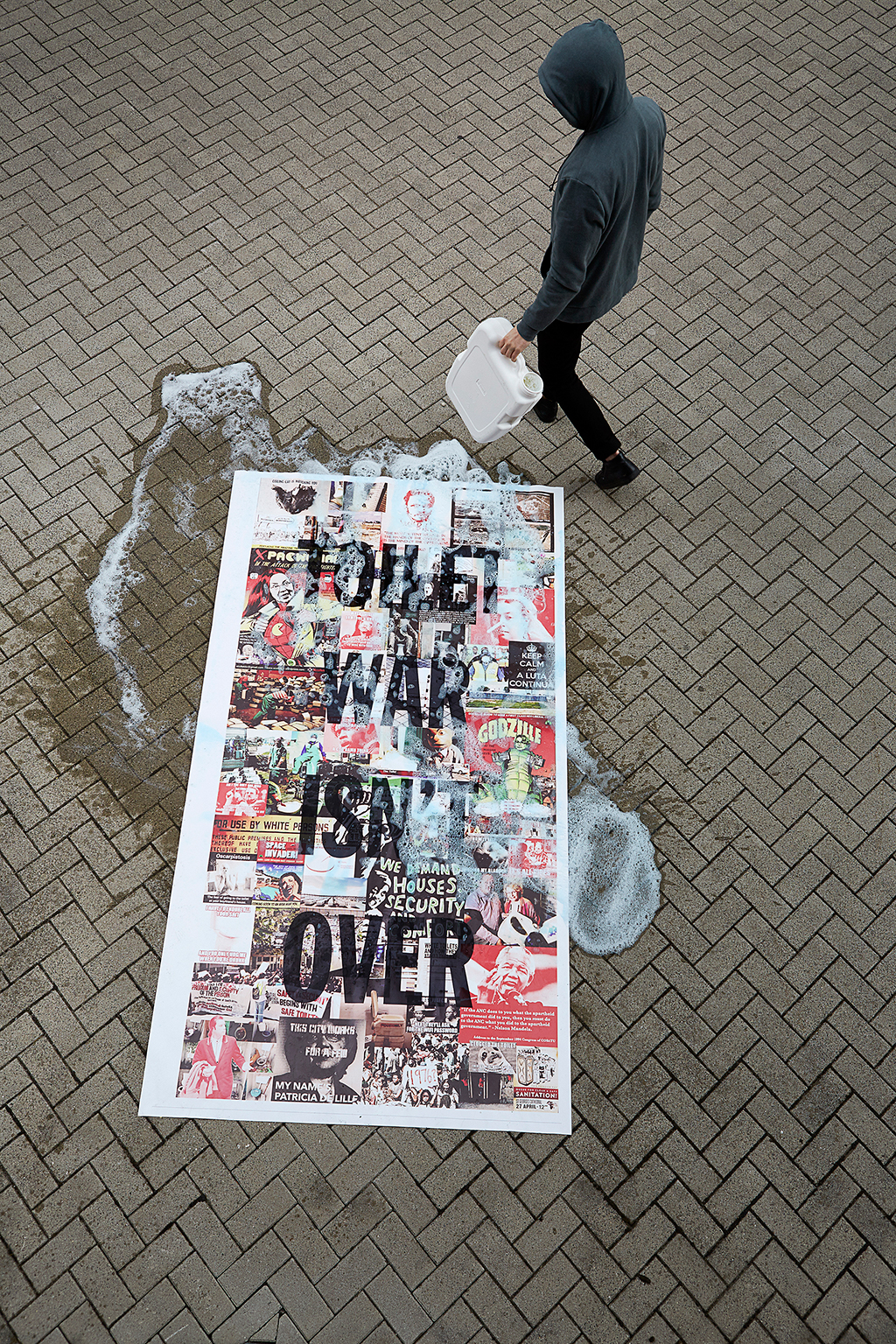

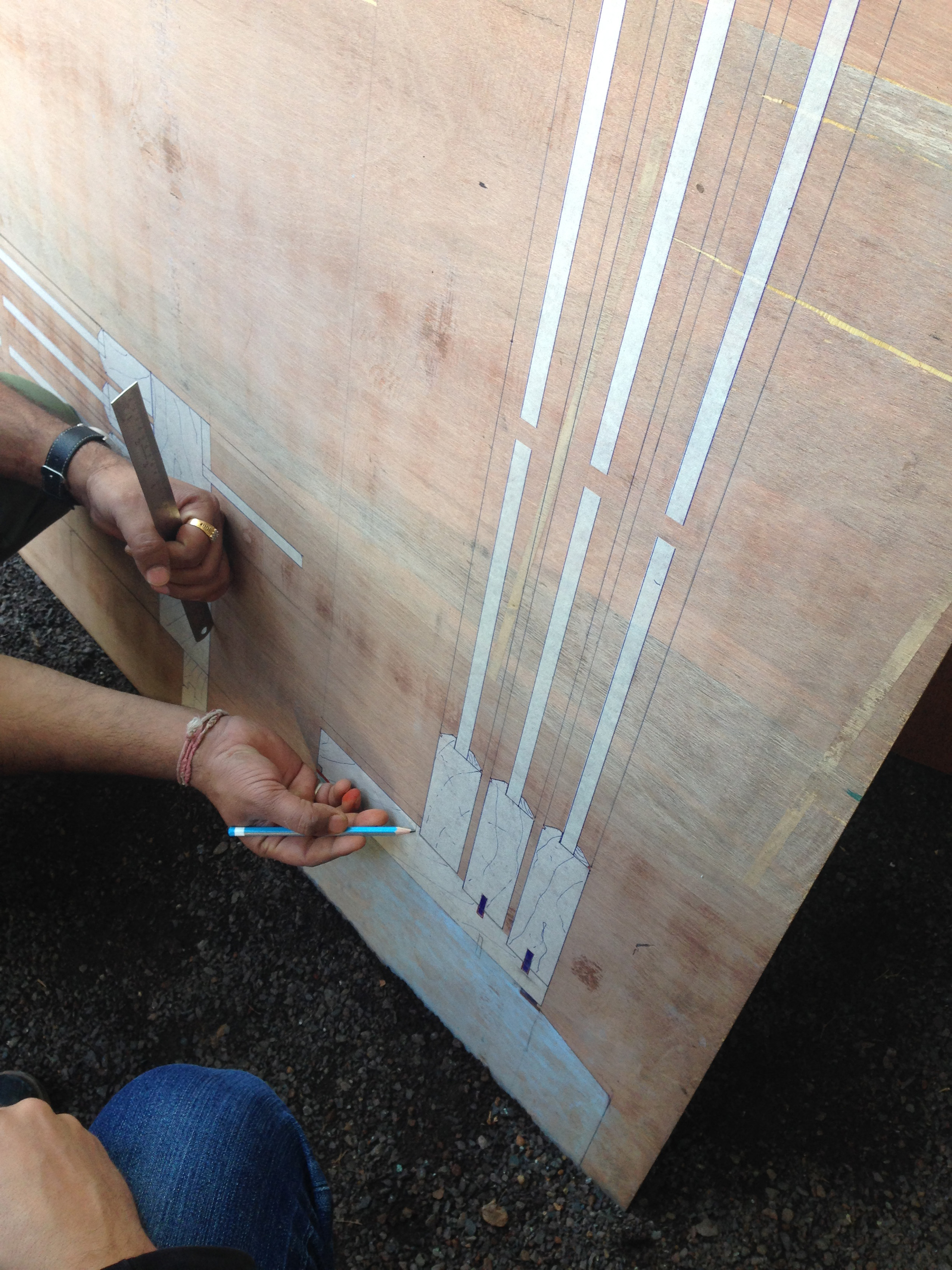

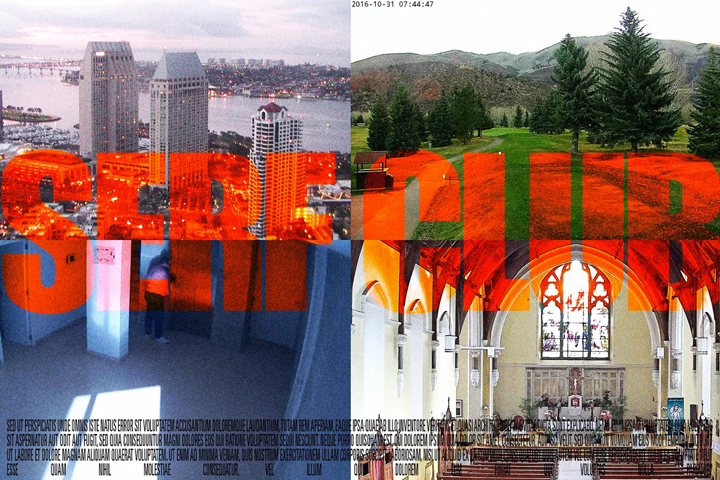

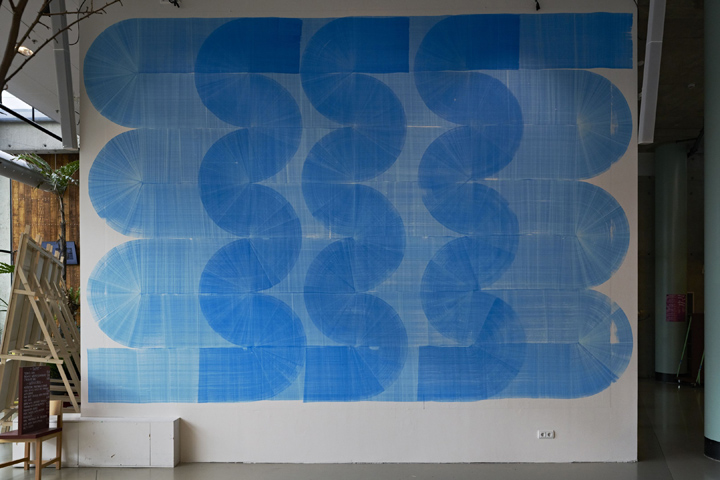

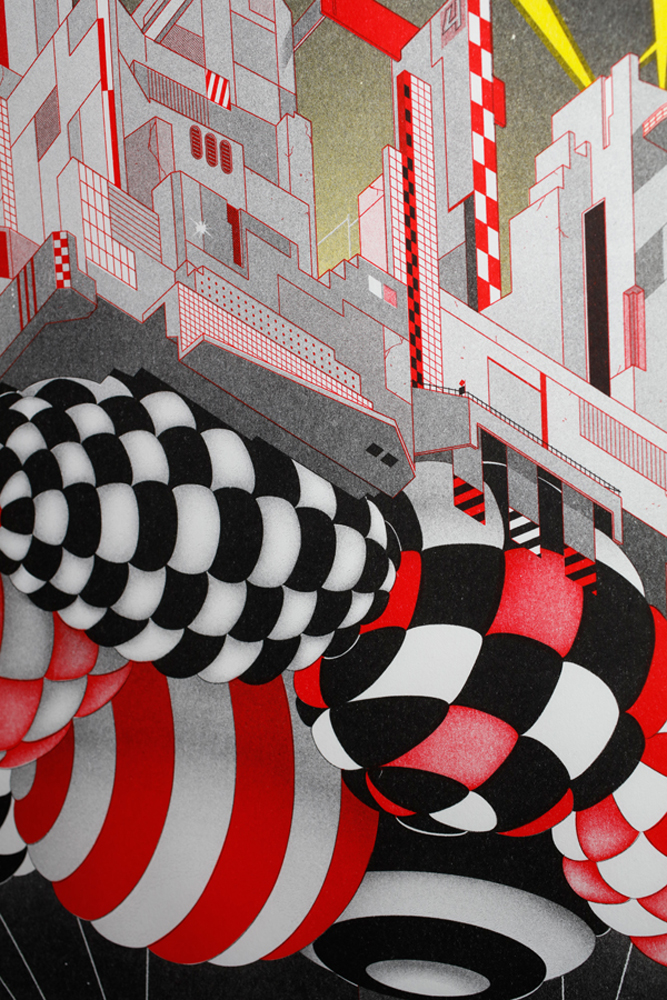

Professionals in art direction, storytelling or city making are given the opportunity to consolidate their practice. Street artist Saïd Kinos (2020 cohort) already had success with his colourful, graphic murals featuring design techniques like collage and typography. Thanks to a talent development grant,

he can now transcend the street art category and expand his practice into being an artist whose canvas extends beyond that of the city. He has mastered digital

techniques, such as augmented reality, animation and projection mapping (projecting moving images onto buildings).

A PRACTICE OF EVOLUTION

The advancement of an individual or collective practice thus coincides with the development of the entire discipline. The fixed principles of traditional design

disciplines, such as fashion, design and architecture, are explored and enriched through new tools, techniques, materials and platforms. By now, everything is mixed

up: street, museum and website; cartography and aerosol; witchcraft and 3D printers. These talented designers respond to social developments and leave their mark

on them, thereby shaping tomorrow's society, which is the ultimate proof of the necessity of talent development.

Text: Jeroen Junte

Longread Talent #2

Me and the world

Post-crisis design generation seeks (and finds) its place in vulnerable future

Over the past seven years, the Stimulation Creative Industries Fund NL has supported over 250 young designers with the Talent Development grant. In three longreads, we look for the shared mentality of this design generation, which has been shaped by the great challenges of our time. In doing so, they examine how they deal with themes such as technology, climate, privacy, inclusiveness and health. In this second longread: design talent is nourished by a sense of urgency. ‘If we do not turn the tide, who will?’

15 September 2008. 12 December 2015. 17 March 2018. These may seem like random dates, but these moments have left their mark on the contemporary design field. On

15 September 2008, the Lehman Brothers investment bank in New York went bankrupt. The ensuing severe financial crisis exposed the disarray of the global economic

system. On 12 December 2015, 55 countries (now 197) concluded a far-reaching Climate Agreement recognising climate change as an indisputable fact. The industrial

depletion of existing raw materials and energy supplies is now ‘officially’ unsustainable. And on 17 March 2018, The New York Times reported

on large-scale political manipulation by the data company Cambridge Analytica. Fake news and privacy violations shattered the twentieth century’s democratic

ideal.

These events – and more, for that matter – highlight the world’s continuing crisis conditions. The more than 250 designers the Talent Development

Scheme of the Creative Industries Fund NL has supported since 2014 were trained during, and thus shaped by, these crises. They belong to the last design generation

with a clear memory of 9/11 – a generation motivated by a sense of urgency. They understand that if we don’t turn the tide, then who will? They are

also devoid of arrogance and well aware of the limitations of their expertise and the disciplines in which they work. Whether product design, fashion, digital design

or architecture, they do not harbour the illusion that they have that one all-encompassing solution.

Irene Stracuzzi, The legal status of ice

MAPPING THE MONEY FLOWS

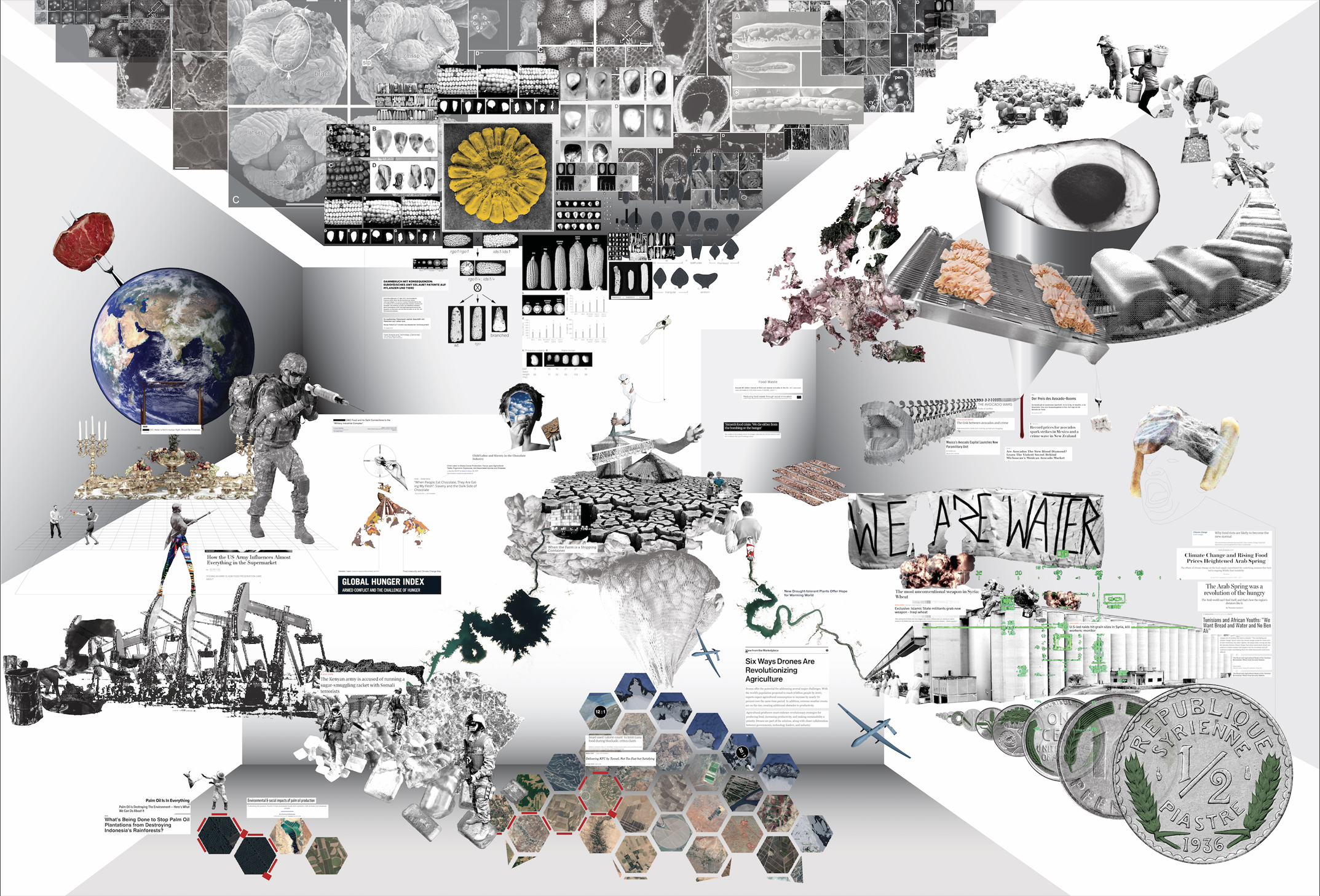

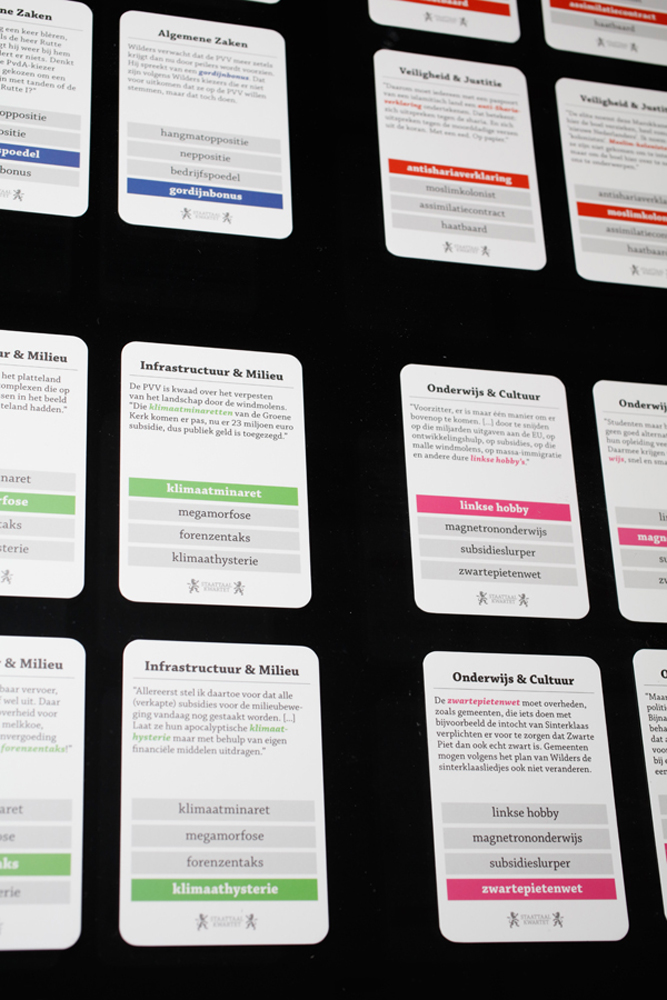

However, communication is a potent weapon, as graphic designer Femke Herregraven (2015 cohort) understands. She delved into and visualised the financial

constructions behind the neoliberal world economy. Herregraven focused on offshore structures and the disconnect between capital and physical locations. Through

a serious game, she playfully introduced you to international tax structures in faraway places. Her Taxodus draws from an extensive database that processes

various international tax treaties and data from companies and countries. Becoming rich has never been so fun and easy. She also investigated the colonial history

of Mauritius and this Indian Ocean island’s new role as a tax haven. Herregraven’s meticulous research and surprising designs reveal hidden value systems

and clarify their material and geographical consequences. To reform unbridled capitalism, one must first know its pitfalls.

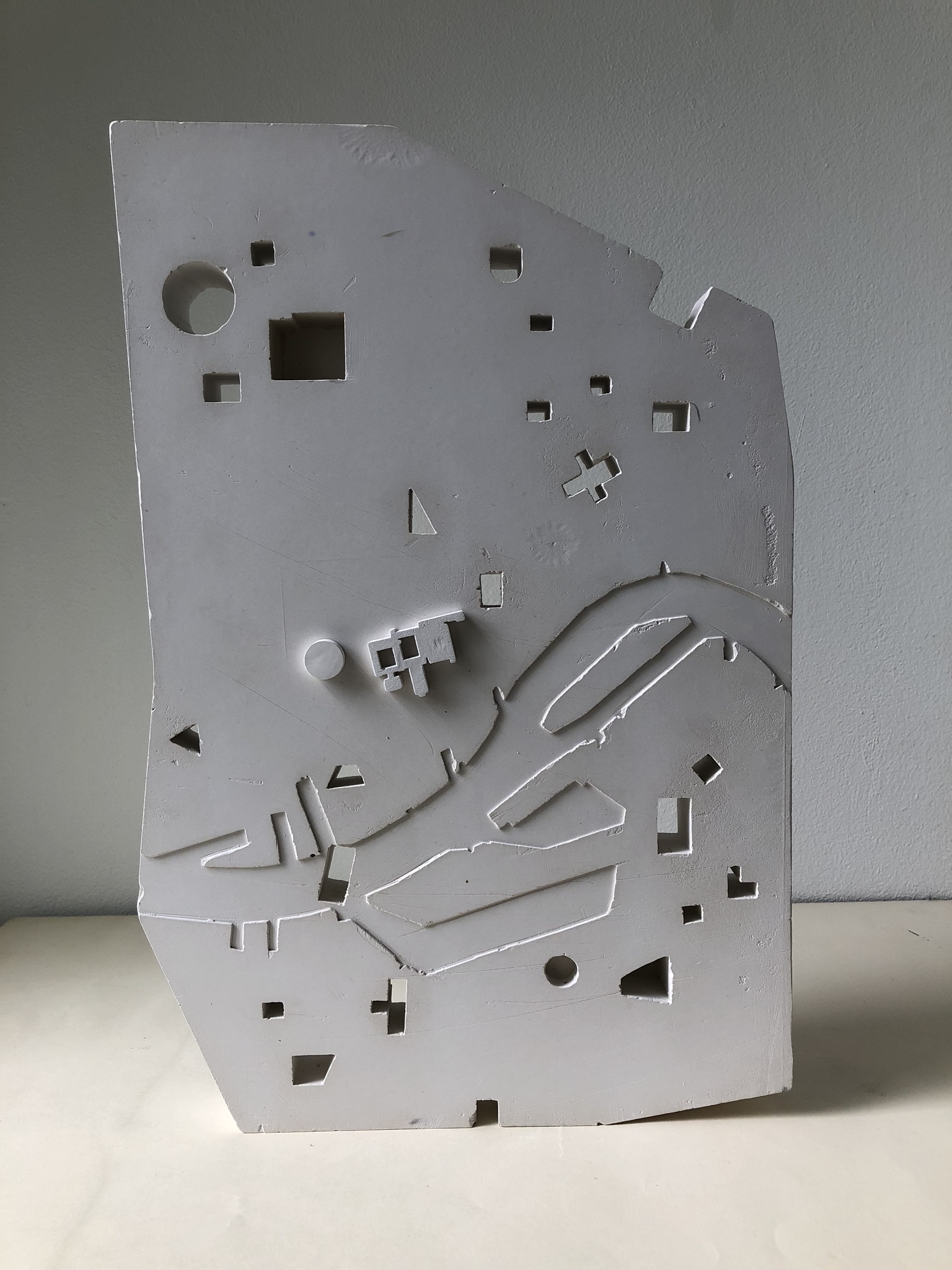

Knowledge is also power. Thus these designers are trying to determine their place in an increasingly vulnerable world. Vulnerable in a very literal sense because

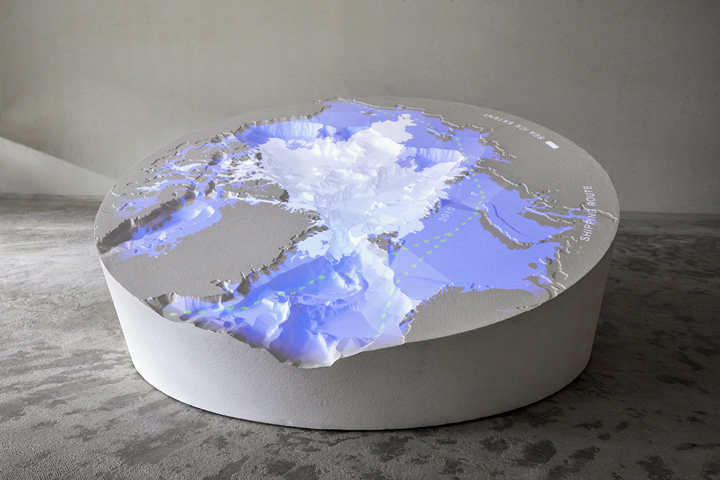

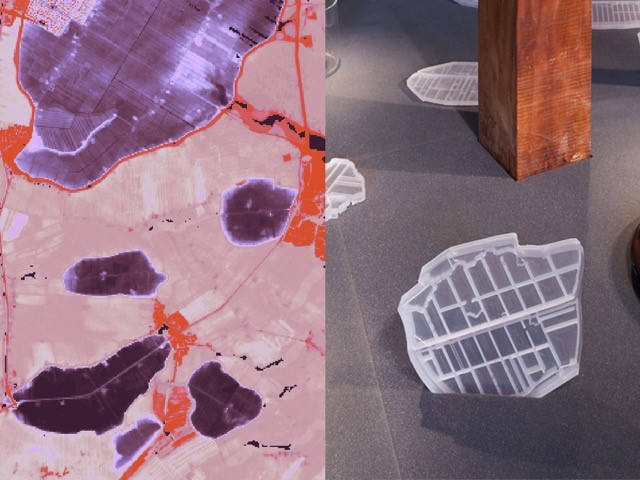

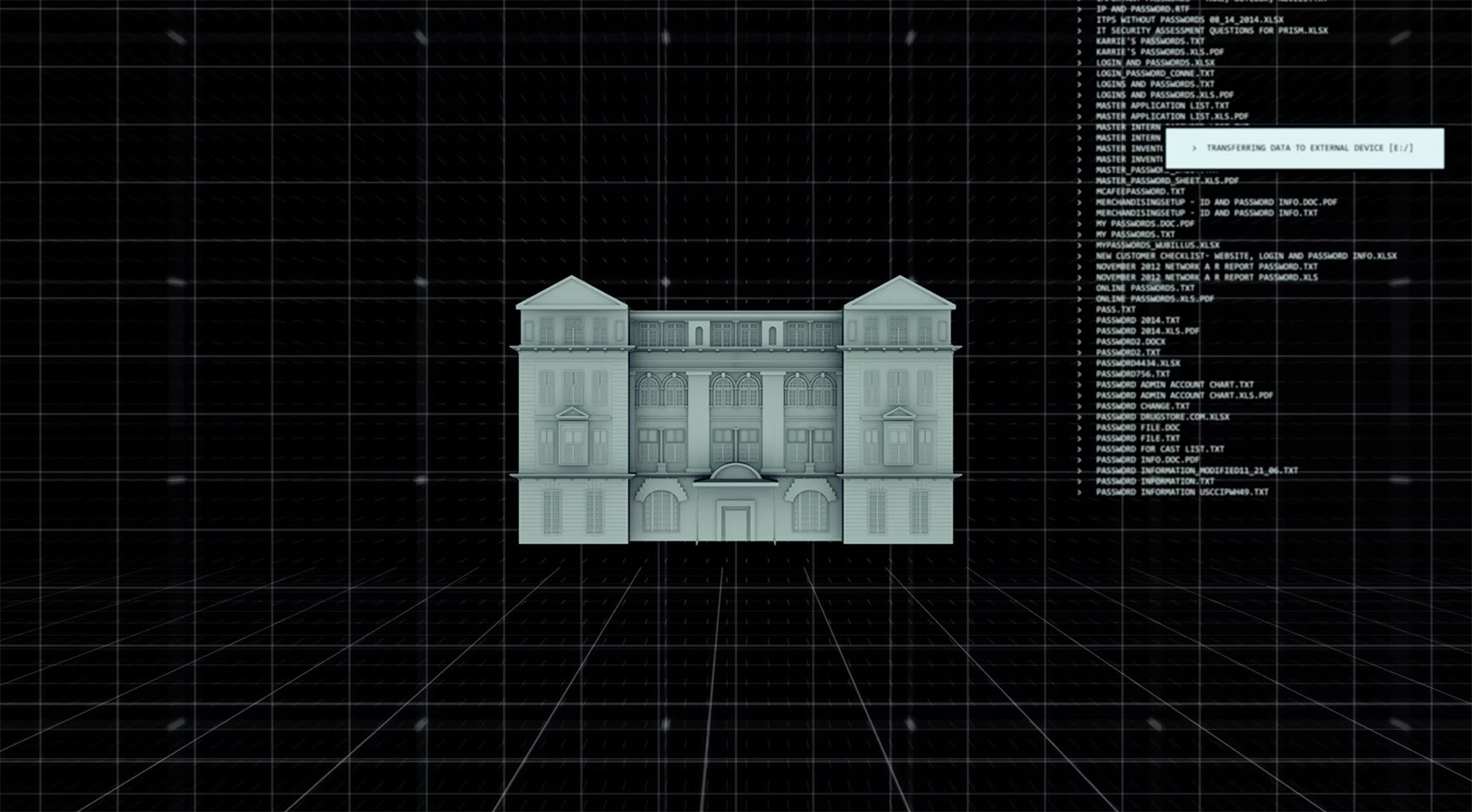

climate change is perceived as the most dangerous threat. As graphic designer Irene Stracuzzi (2019 cohort) demonstrates, geopolitical forces also

determine the playing field here. Her installation The Legal Status of Ice details how the five Arctic countries – Russia, Canada, Denmark, Norway

and the US – are laying claim to the North Pole. After all, immense oil and gas fields may lie beneath the melting icecaps. But shouldn’t the disappearing

ice, which has shrunk by half since the late 1970s, be the issue? Stracuzzi has mapped this contemporary imperialism in a giant 3D model of the North Pole, onto

which she maps the overlapping claims and other data. The legal status of ice concerns not only the North Pole but also the uranium mines in Angola and the new

space race in search of lunar minerals. It is about a system of exploitation and colonialism. The influential curator Paola Antonelli selected Stracuzzi’s

work for the Broken Nature exhibition at the 2019 Triennale di Milano. No one can now claim we didn’t know.

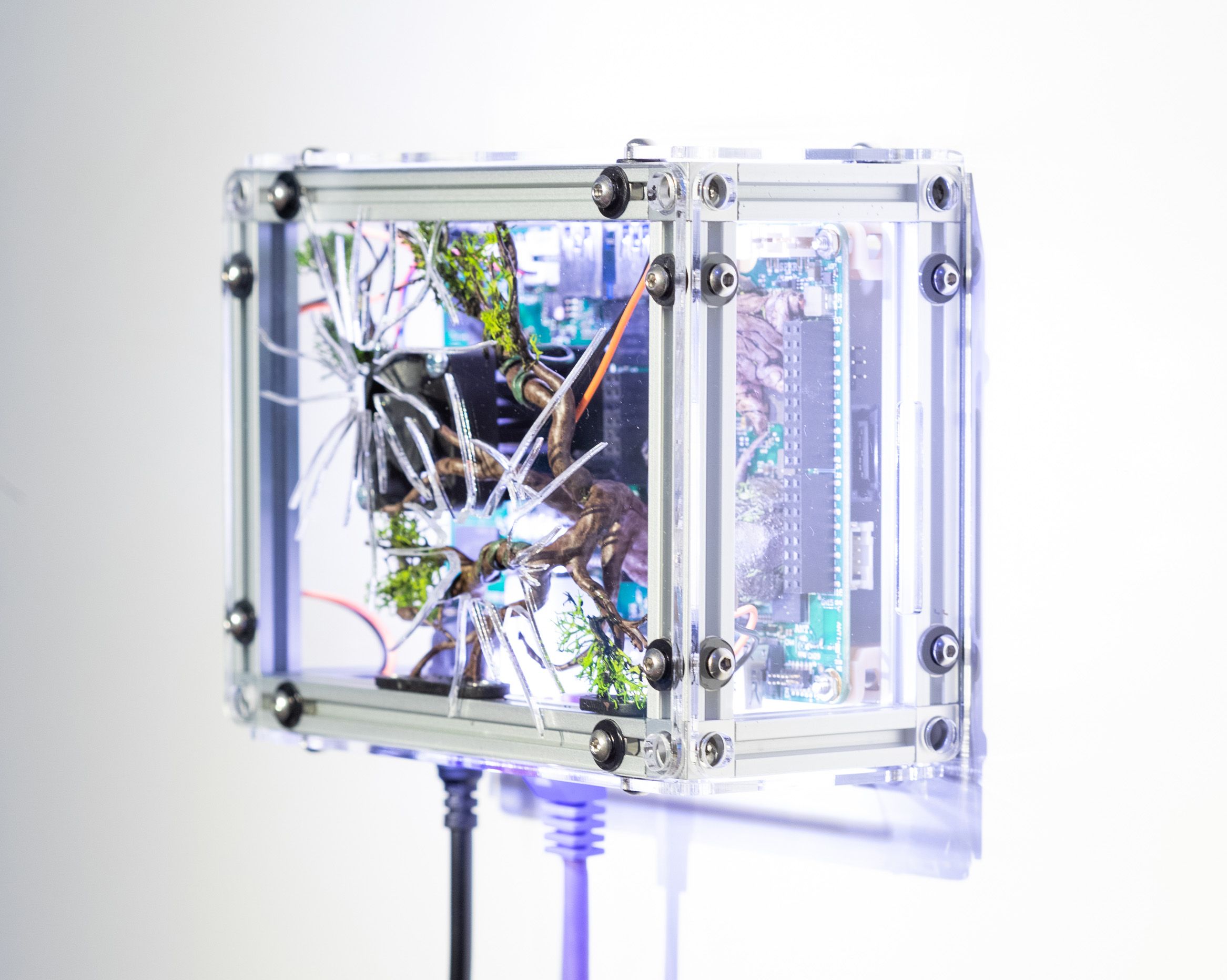

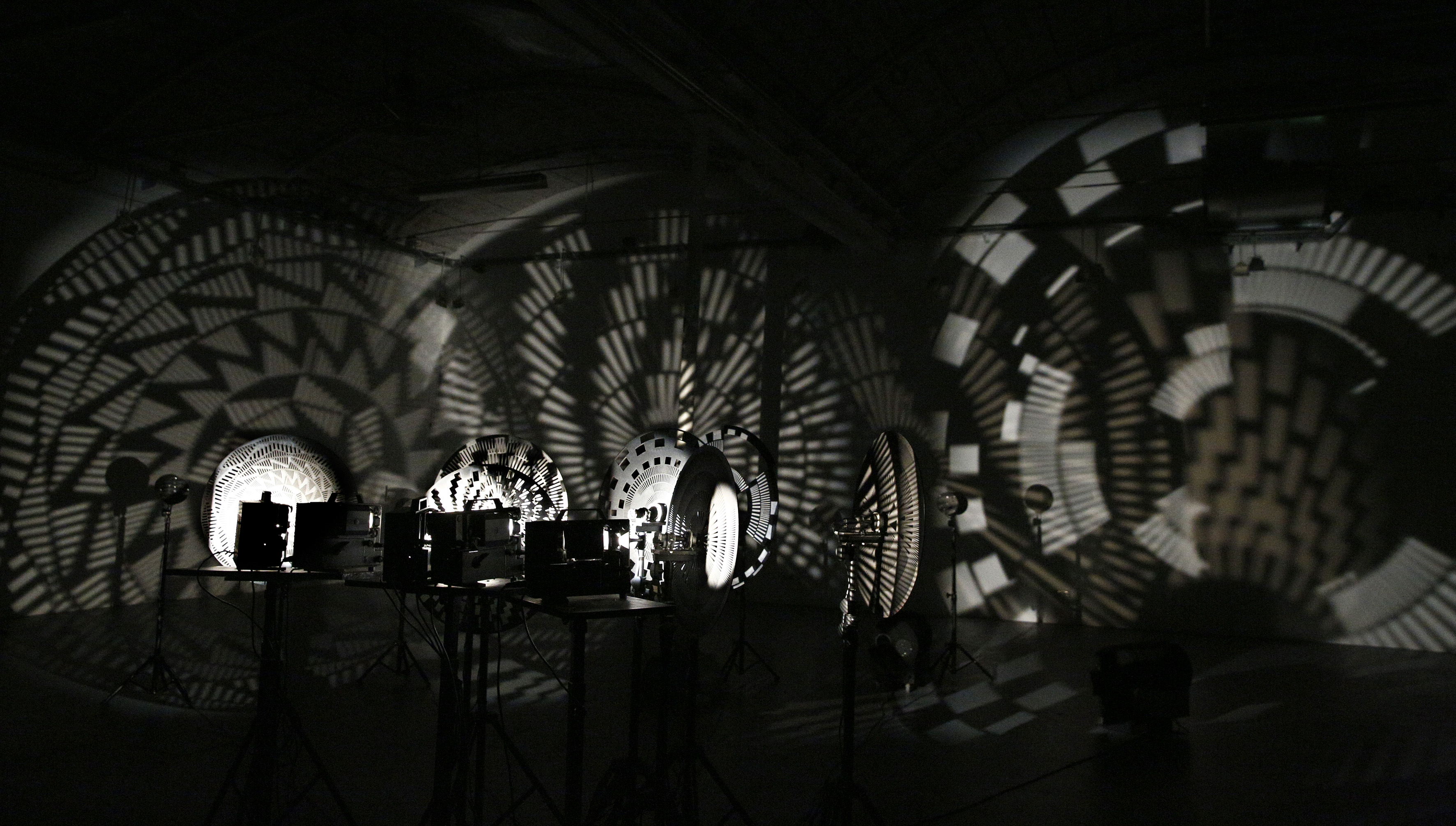

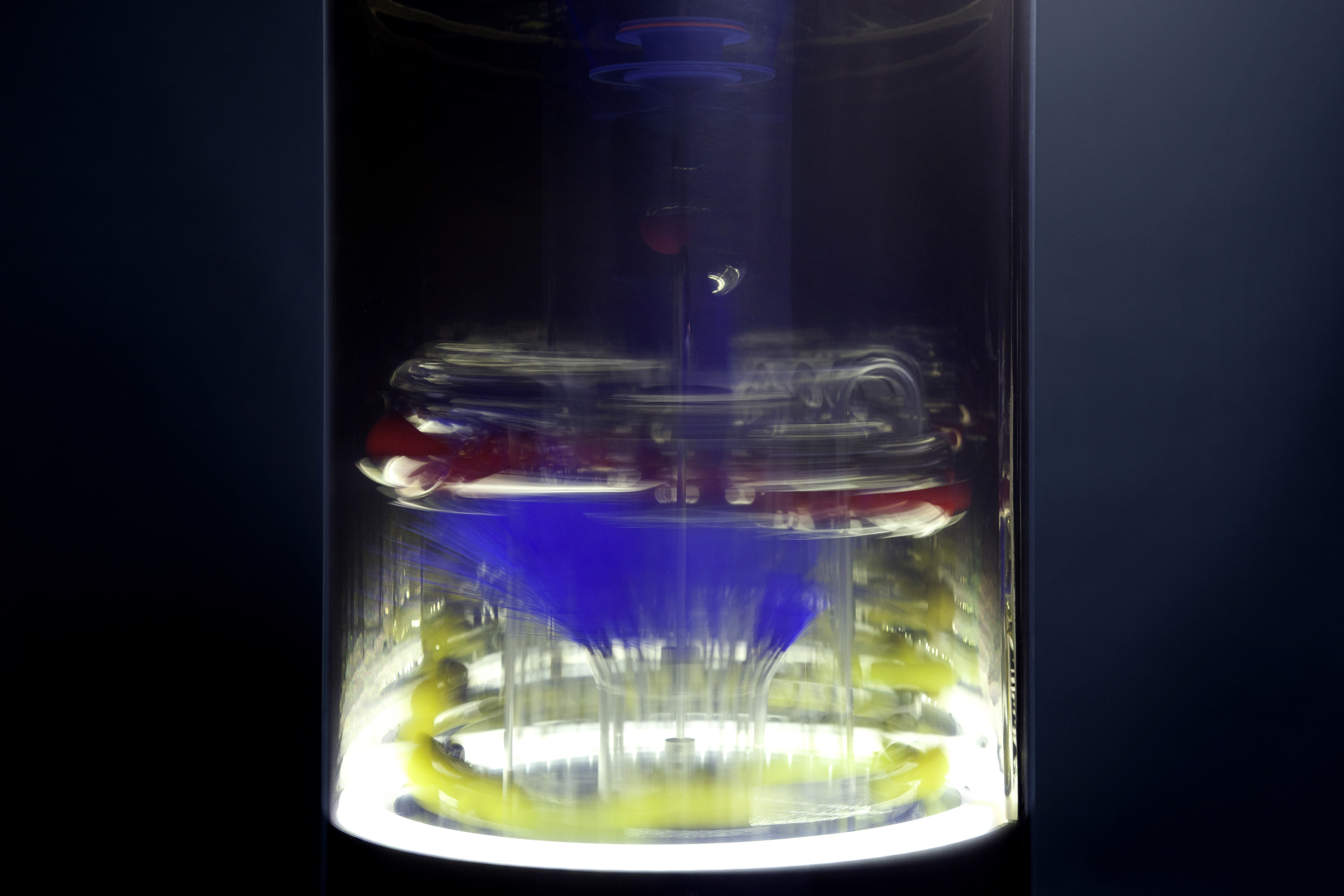

LIVING LAMPS

The realisation that the complexity of the climate crisis is too great to confront alone is profound. Designers eagerly collaborate with other disciplines. For example,

Marco Federico Cagnoni (2020 cohort) is researching latex-producing edible plants with Utrecht University. Corn and potatoes, among other plant

varieties, are still grown as raw materials for bioplastics, but the production process discards the nutrients. Cagnoni is studying food crops whose residual material

is also processed into fully-fledged bioplastics.

Designers seek a symbiosis with nature from an awareness that we can no longer exploit Earth with impunity. The roadmap is diverse, and nature is protected, imitated,

repaired or improved. Let us not forget, we are in the Anthropocene: the era in which human activity influences all life on Earth. But if humankind can destroy

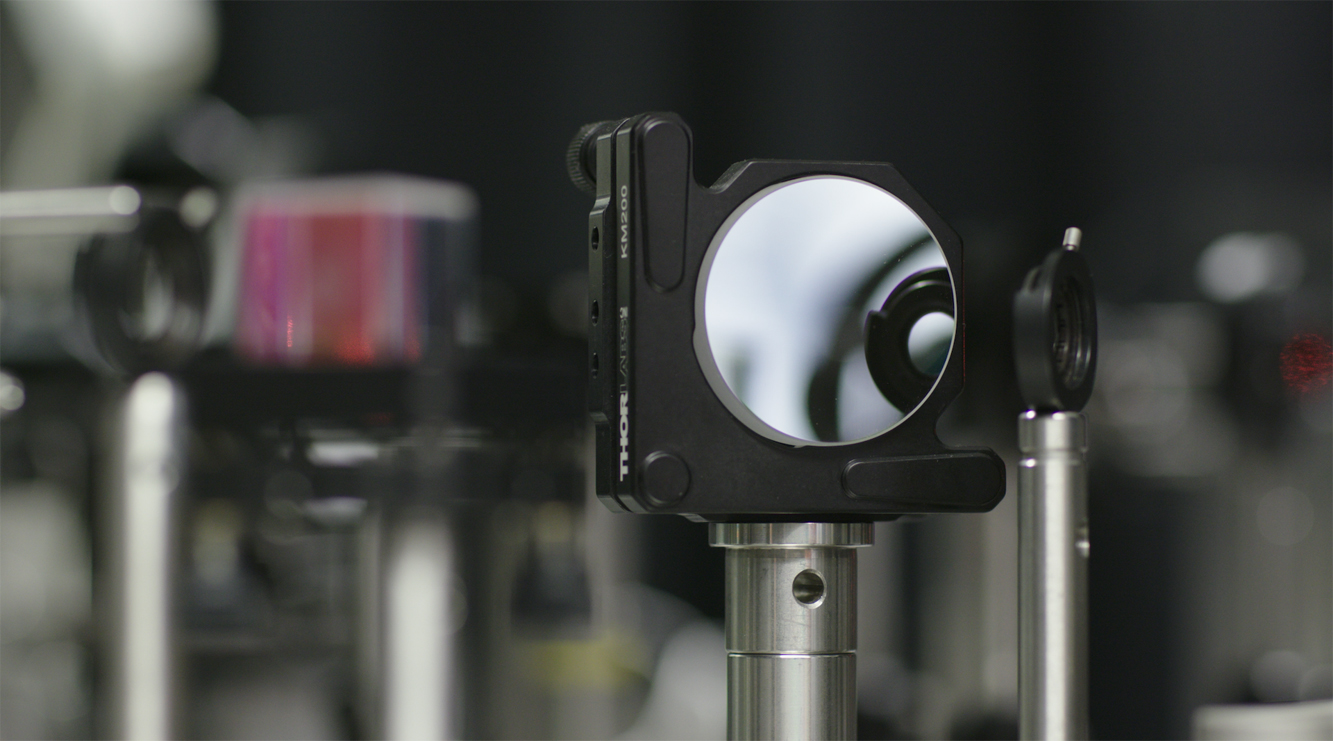

nature, then humanity can also recreate it. Biodesigner Teresa van Dongen (2016 cohort) collaborated with microbiologists from TU Delft and Ghent

University to develop the Ambio lamp based on luminescent bacteria. The lamp features a long, liquid-filled tube in which marine bacteria live. When the

tube moves, it activates the bacteria to give off light. The better the bacteria are cared for, the more and longer they give light. As well as being a sustainable

alternative, her Ambio lamp also functions as a powerful means of communication. So working together with nature is possible; we have simply forgotten

how to do it.

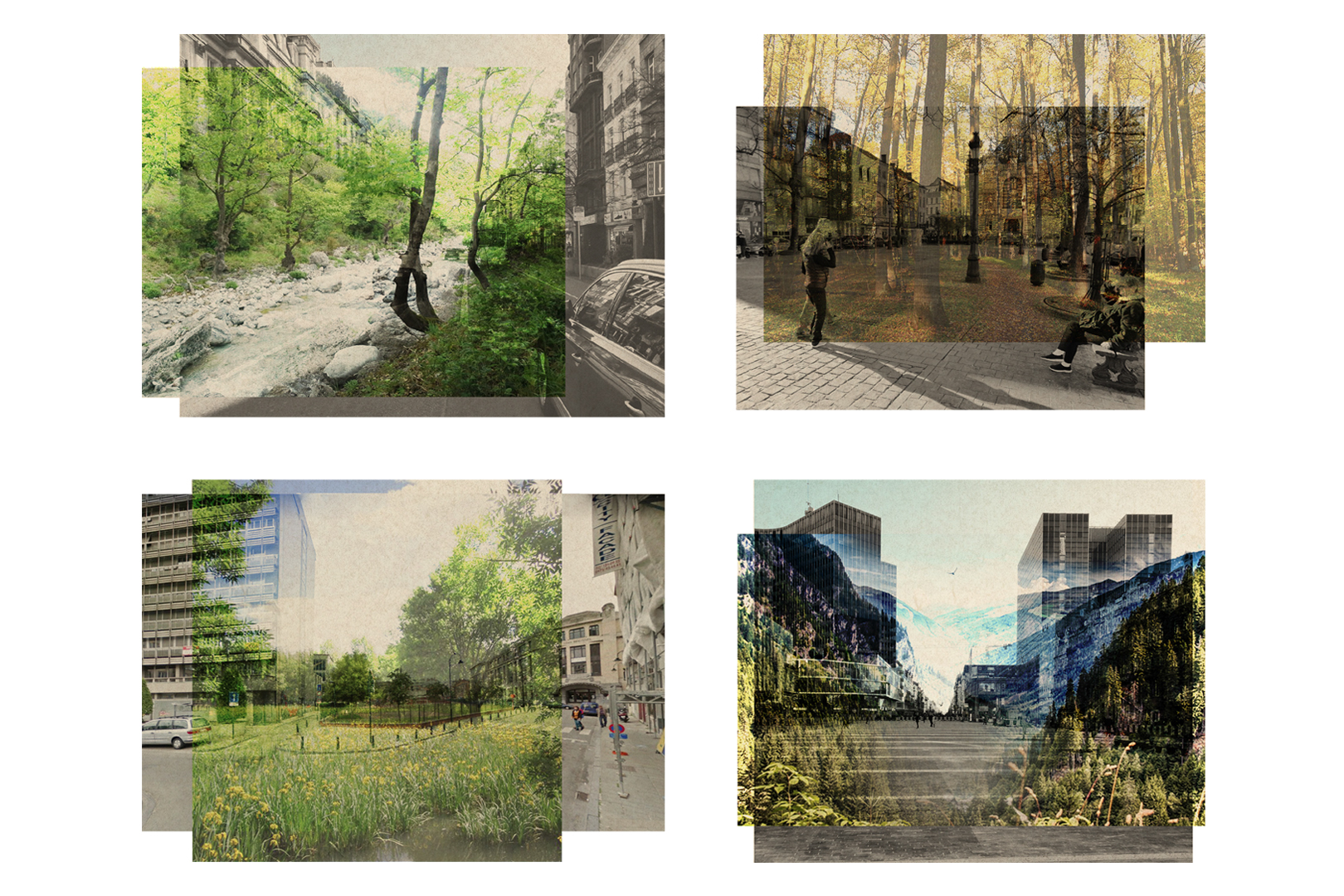

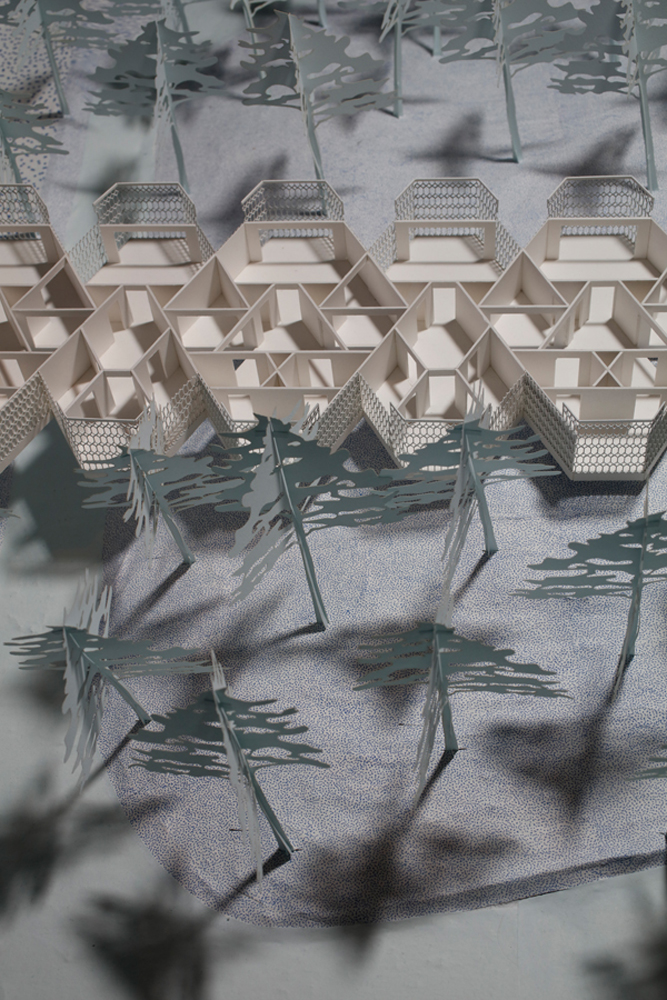

This situation explains why designers are looking for ways to restore our relationship with nature. Architect Anna Fink (2020 cohort) proposed a

country house consisting of rooms scattered in woods, meadows and a village. Residents must maintain their Landscape as House by felling, planting, mowing,

building and repairing. The essence of this fragmented ‘house’ is a daily rhythm of movement from room to room and an awareness of the environment,

time and space. Routines and rituals are rooted in the weather’s changes. Seasons become a domestic experience. Fink drew on the age-old, semi-nomadic lifestyle

of her ancestors in the valley of the Bregenzerwald in the northern Alps. Here, the hyperlocal offers a solution for global issues.

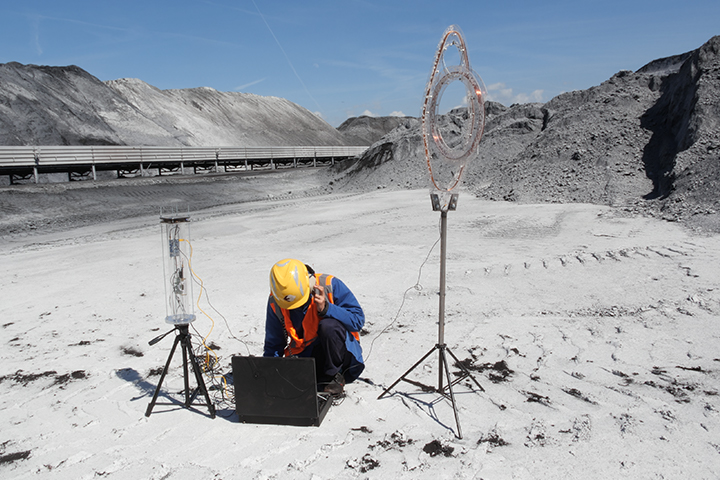

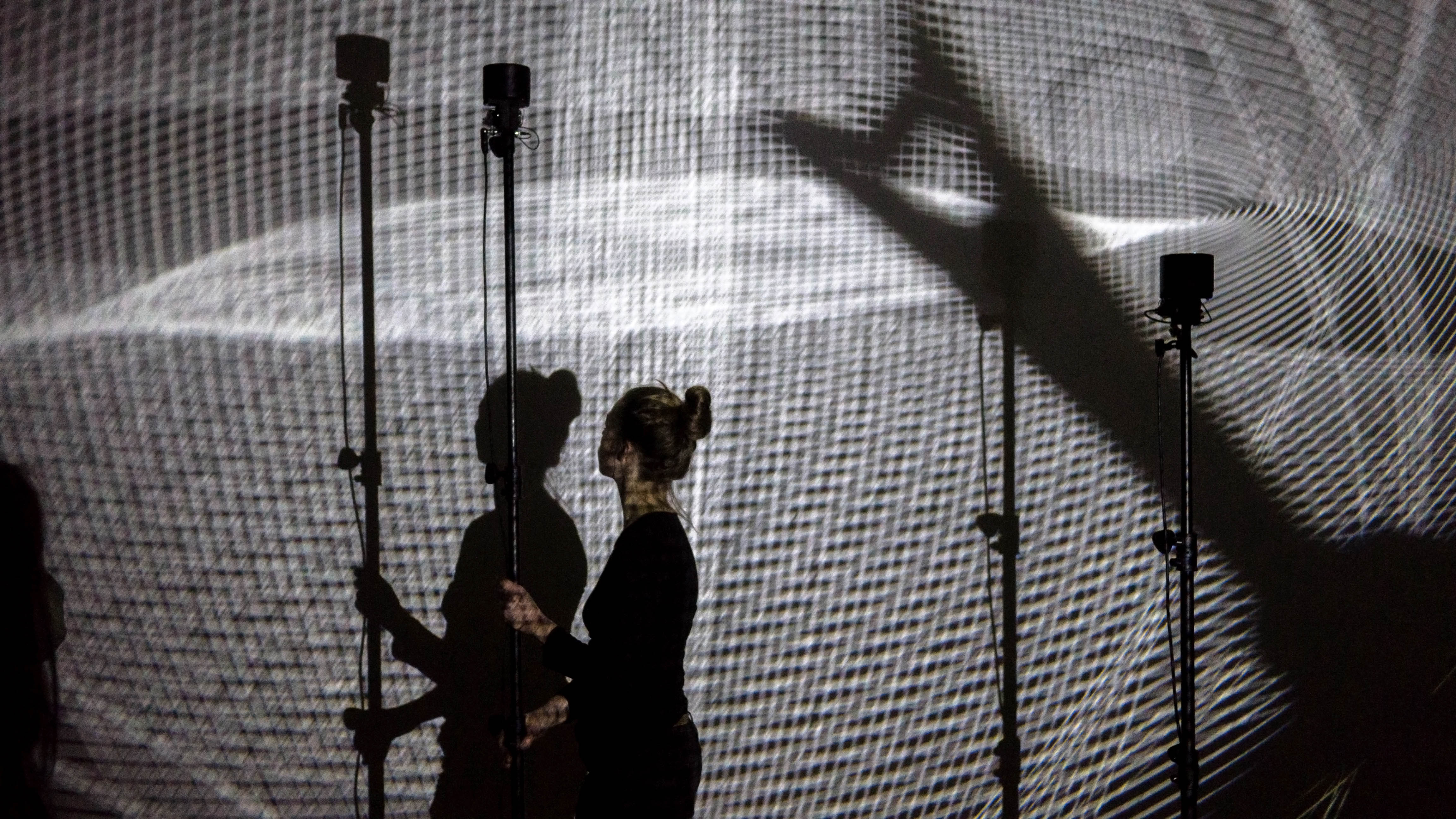

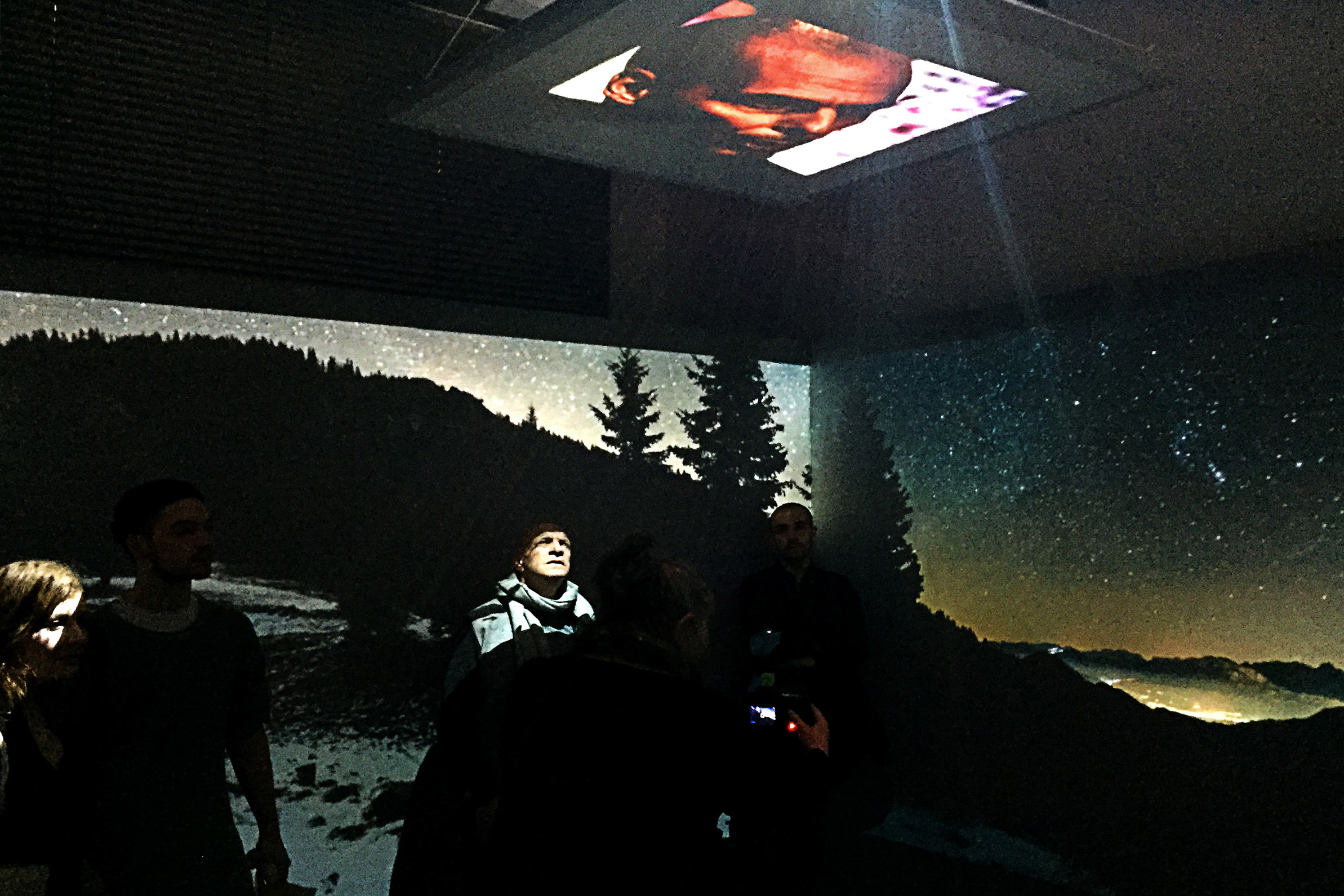

Sissel Marie Tonn i.c.w. Jonathan Reus, Sensory Cartographies

RAW SATELLITE DATA

However, some designers rely on technology to experience nature. Indeed, why should we long for something that no longer exists? The Anthropocene has already begun.

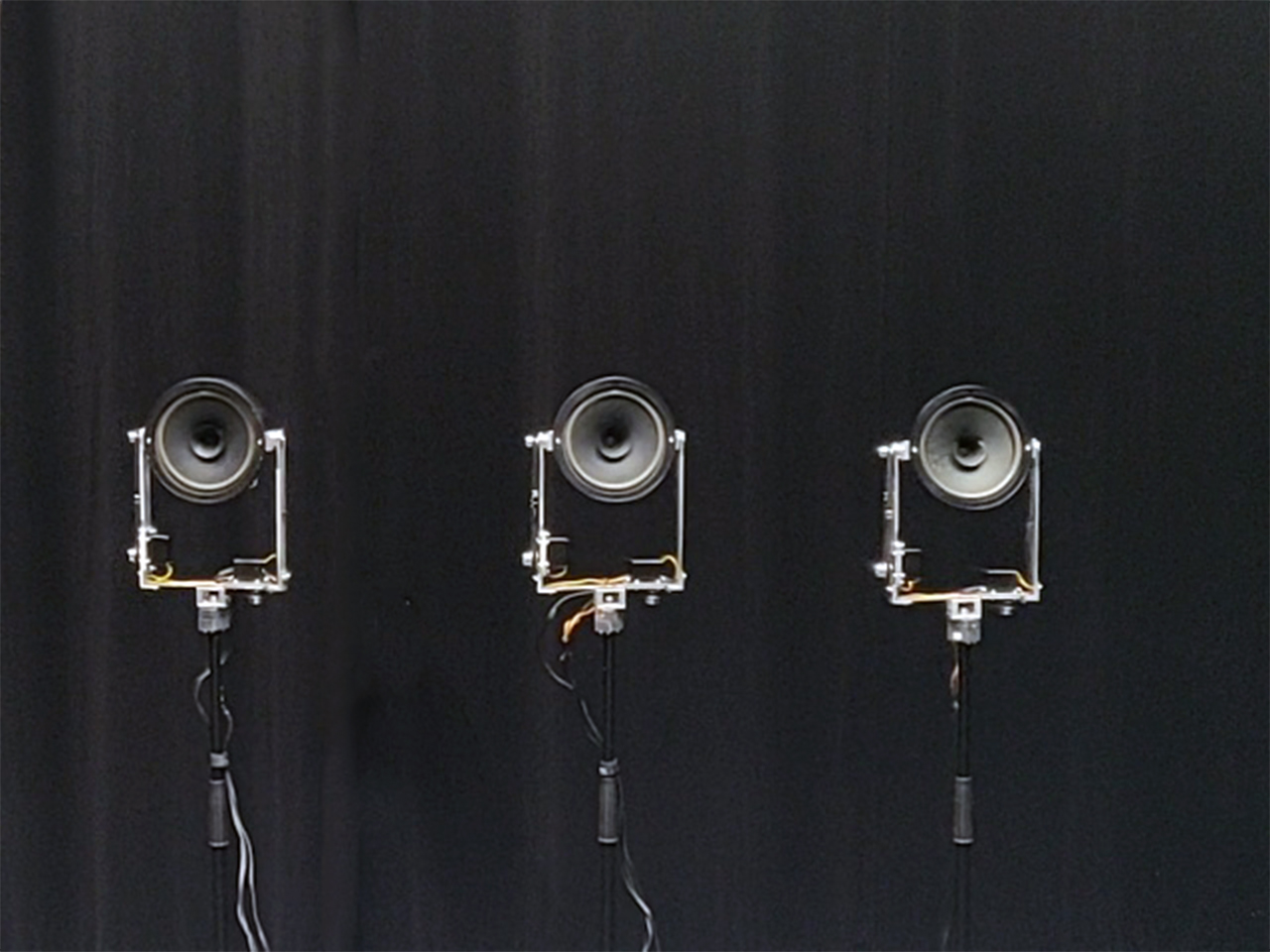

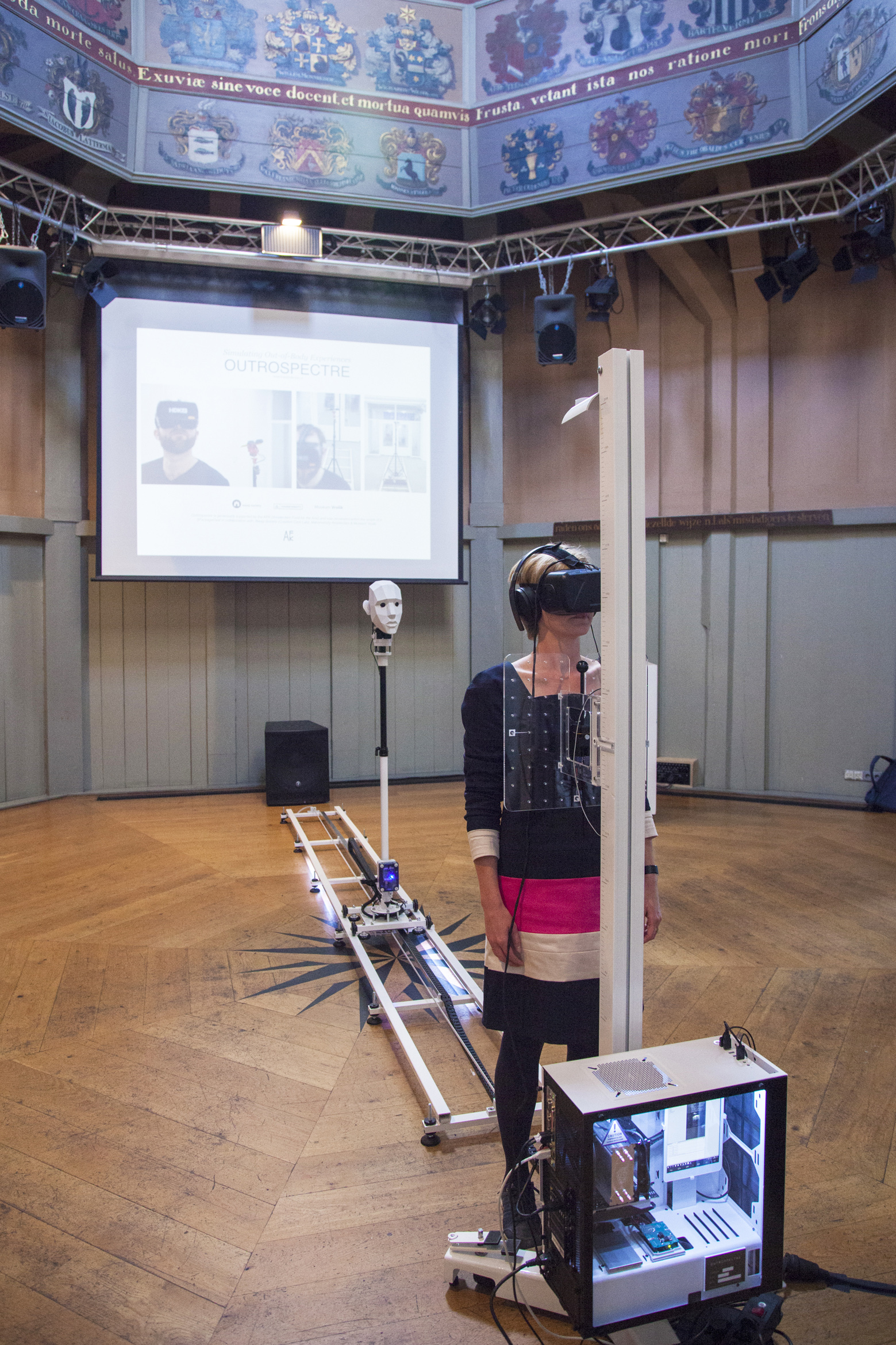

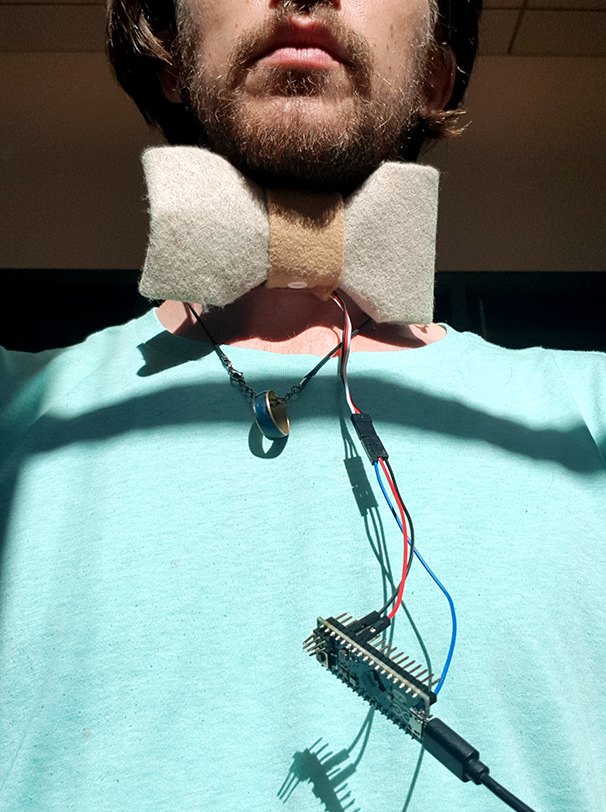

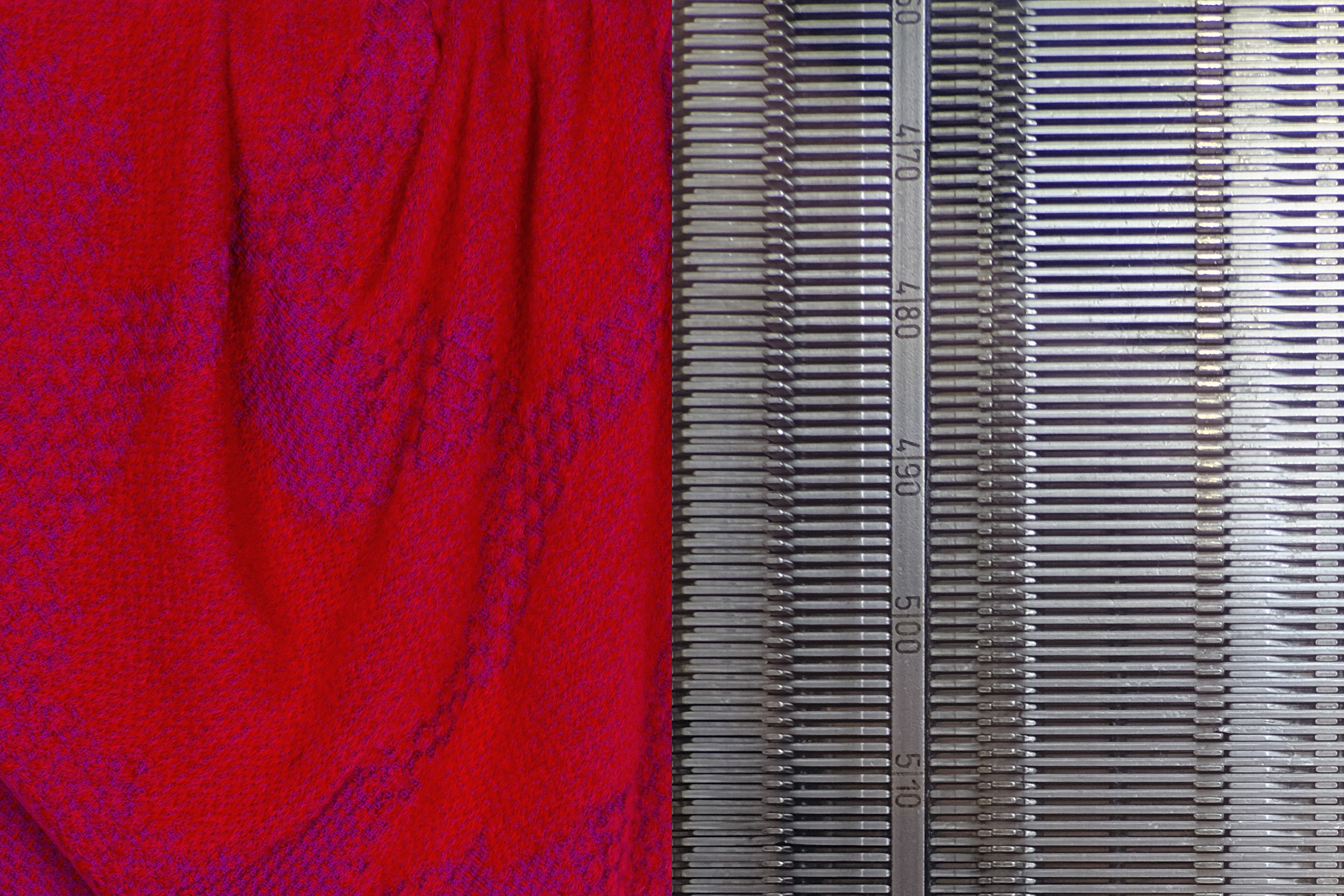

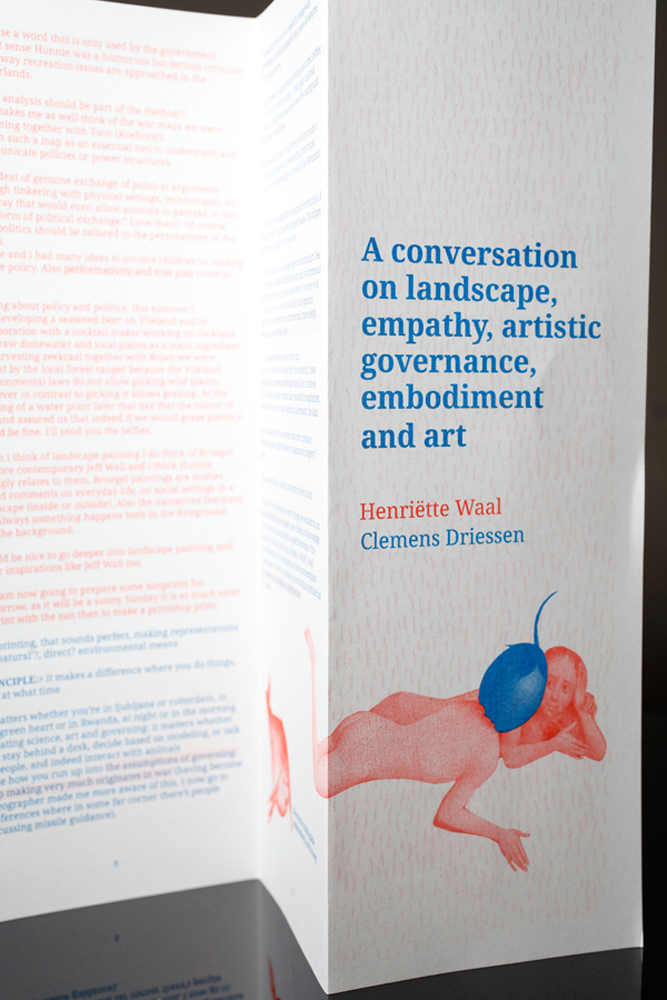

Sissel Marie Ton (2020 cohort) uses scientific data such as seismographic measurements. She combines this complex and abstract data with empathic

conversations with Groningen residents about their earthquake experiences, which are common to this region because of gas field drilling. This layered information

about both the human and geographical aspects of seismic activity was – literally – woven into a wearable vest in collaboration with two fashion designers.

Together with sound artist Jonathan Reus (2018 cohort), she also realised an interactive composition of sonic vibrations to translate the intense

experience of an earthquake to a broad audience. Ton’s installations connect natural processes with technology to make humankind’s impact on Earth visible

and tangible. It is worth remembering that the earthquakes in Groningen were set in motion by humans.

New technologies, such as life science and biohacking, are reshaping our understanding of the natural world. It is no coincidence that these designers are about

as old as Dolly the sheep, which in 1996 was the world’s first successfully cloned mammal. In his Tiger Penis Project, Taiwanese-Dutch designer Kuang-Yi Ku (2020 cohort) extended this genetic replication to healthcare. Many traditional Asian medicines regard the tiger penis as a medicine beneficial for male fertility.

As a result, the tiger, already facing extinction, is under even more threat. Ku – who previously studied dentistry – proposed using stem cells to cultivate

a tiger penis in the laboratory. This immediately raised all kinds of new dilemmas. Is the tiger penis that is laboratory-grown rather than from a wild tiger still

suitable as a traditional Chinese medicine? In short, what are the limits of nature by design?

Kuang-Yi Ku, Tiger Penis Project

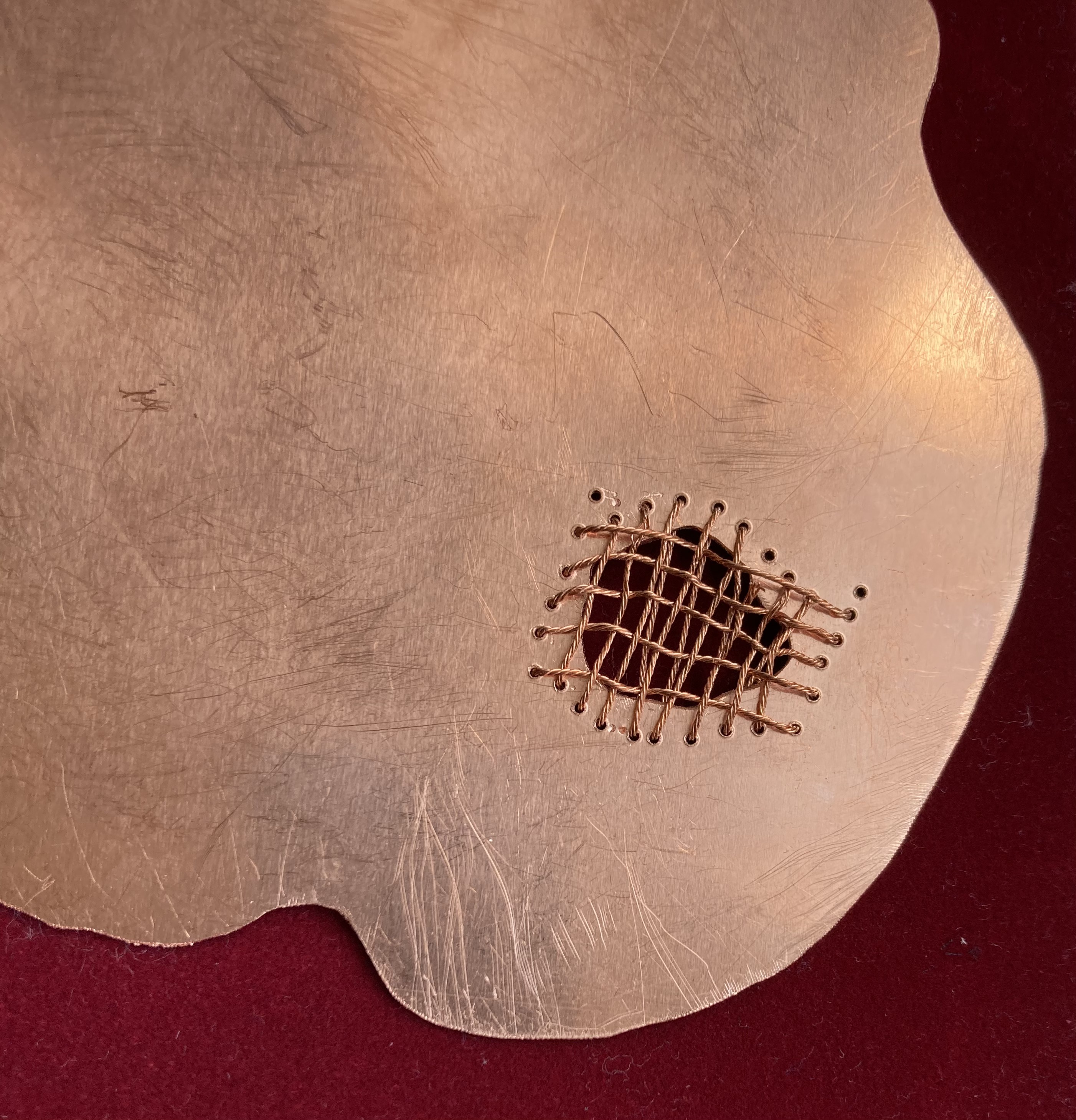

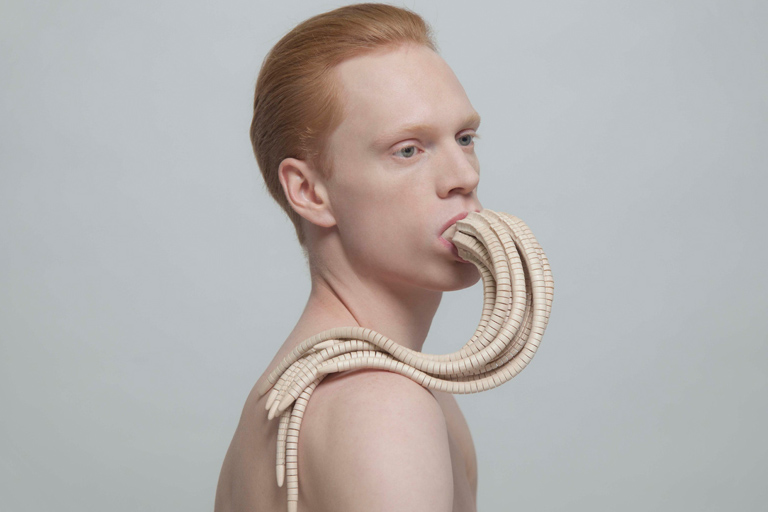

This fusion of biology and technology will eventually lead to a new kind of being: the posthuman. Jewellery designer Frank Verkade (2017 cohort)

developed a scenario for this engineered body with his Paradise project. However, instead of technology, Verkade gives plants and animals a prominent role

in adapting the human body to modern times. The origin of jewellery is, in fact, to be found in prehistoric peoples who used animal forms and natural materials

to harness the mythical forces of nature. By harking back to the ancient, Verkade connects the modern human to its environment.

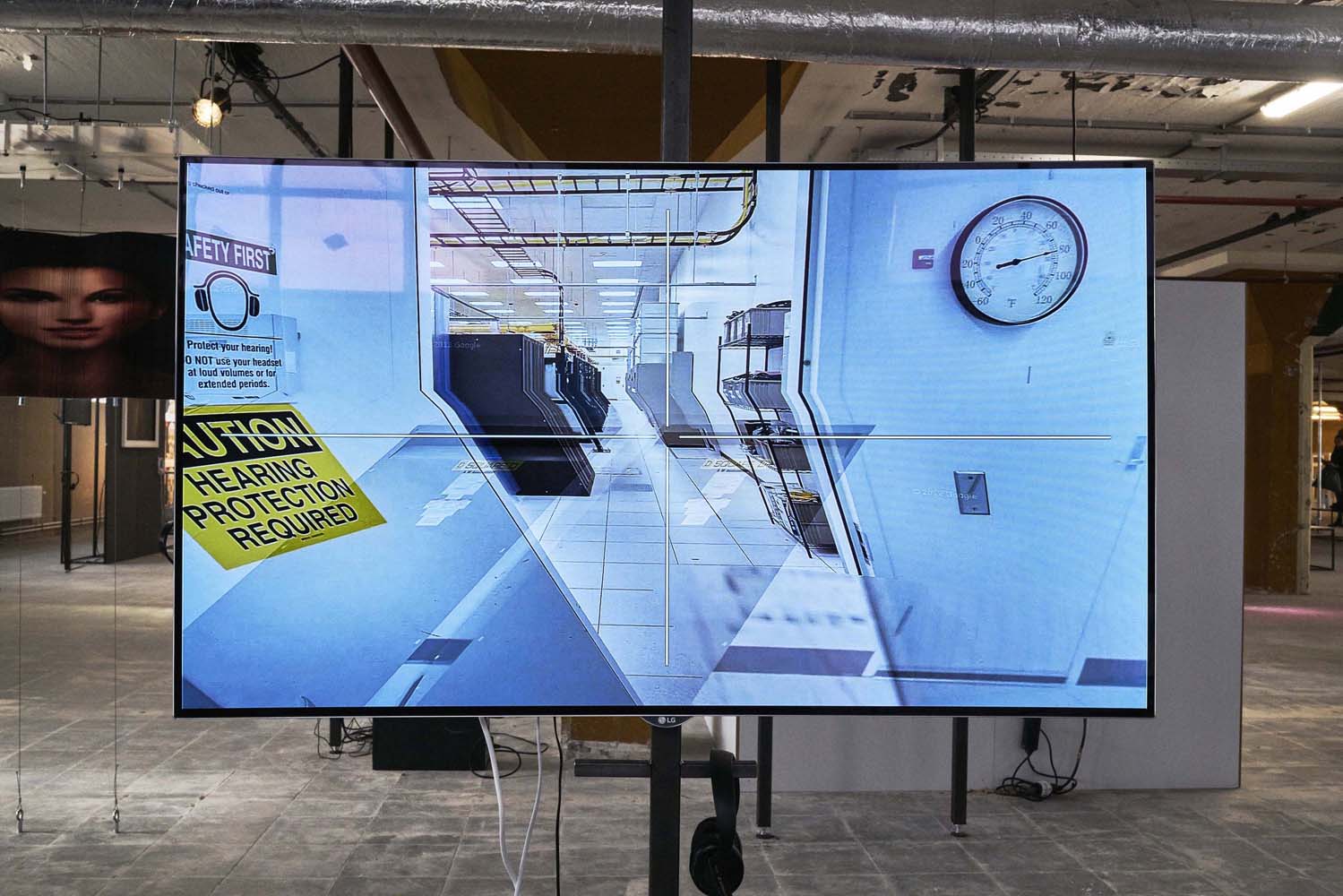

HACKING TECHNOLOGY

If technology becomes such a determining factor for humankind’s future, then surely we cannot entrust the future of our technology to a small group of wealthy,

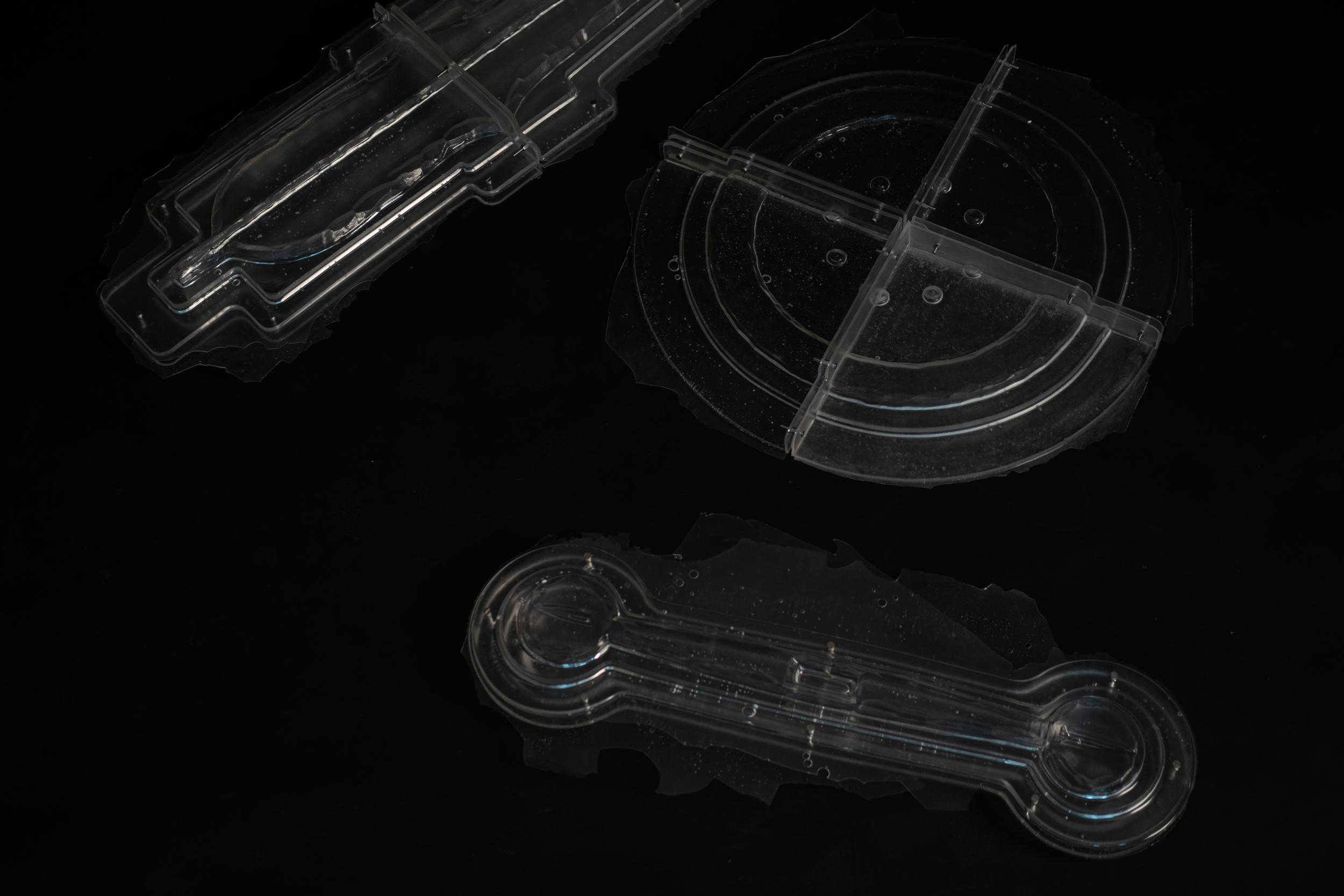

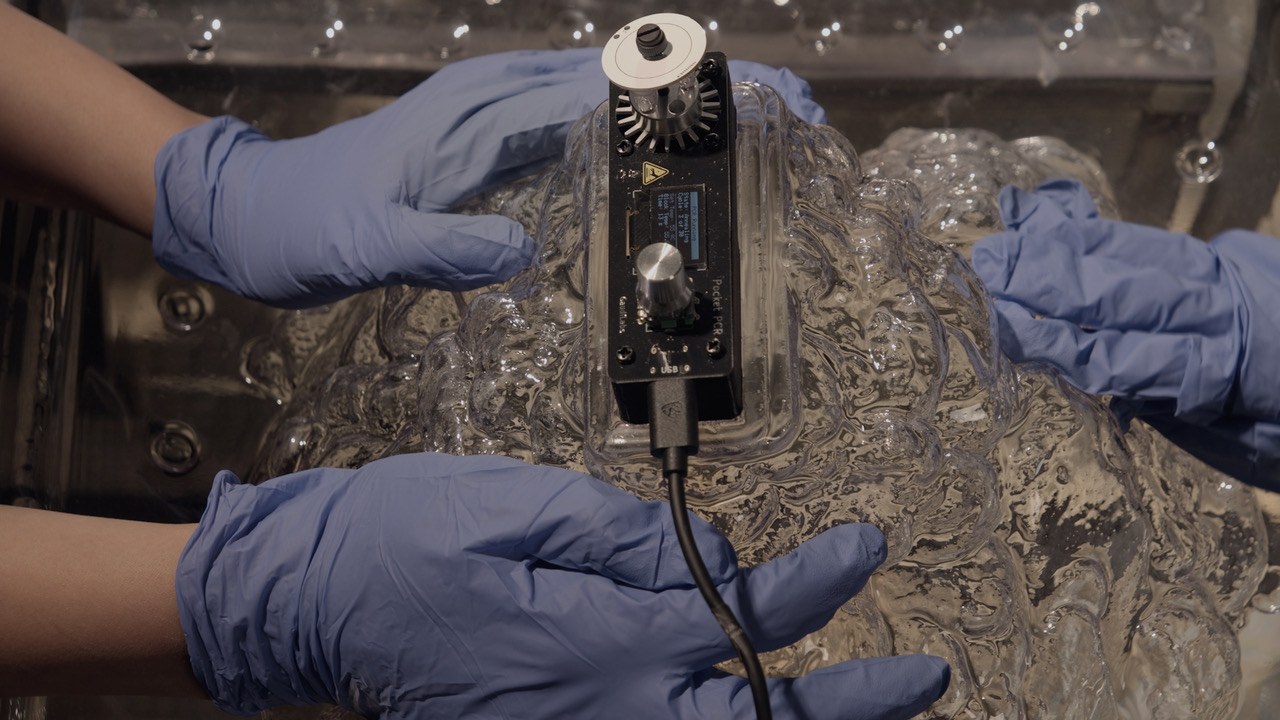

middle-aged white men from Silicon Valley and the European Parliament? According to speculative designer Frank Kolkman (2018 cohort), the discussion

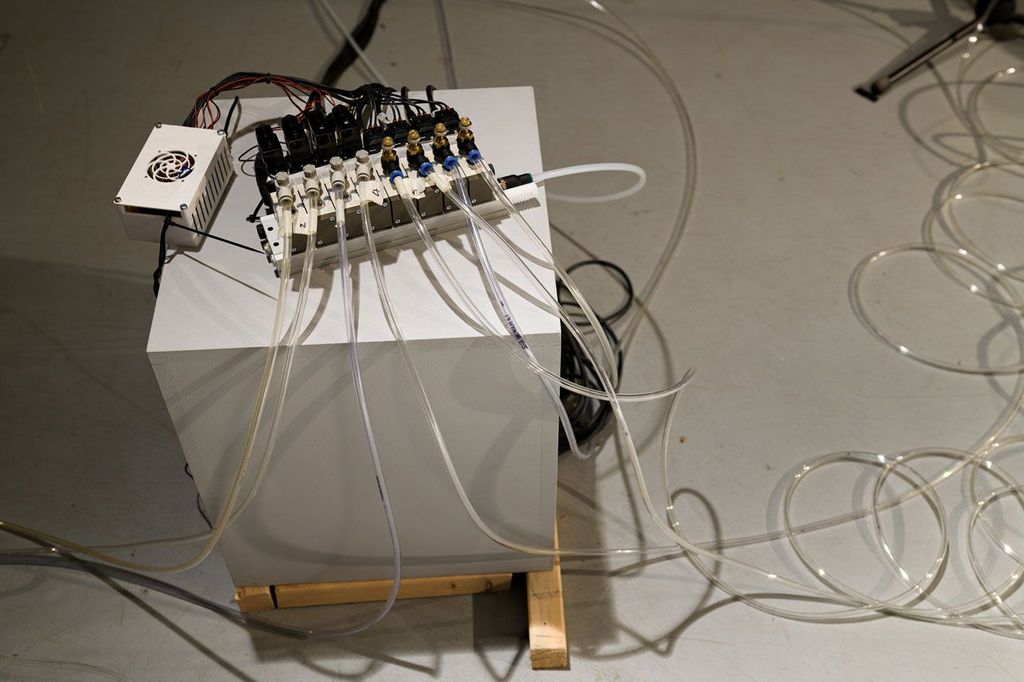

about technology’s quotidian role must therefore be part of our daily life. OpenSurgery is a study into a do-it-yourself surgical robot. These are

already being built using 3D printers and laser cutters by people in the US who cannot afford a doctor. The self-proclaimed design hacker exposes technology’s

social, ethical and political implications. But what do we think of this, and is this something we even want? After all, turning back technology is almost impossible.

Frank Kolkman, Opensurgery

Such ambivalent attitudes towards technology are a common thread in the new design mentality. With the tablet at hand and a laptop at school, this design generation

grew up as digital natives. Technology plays a prominent role in their lives. However, they also know the risks: robotics, big data and artificial intelligence

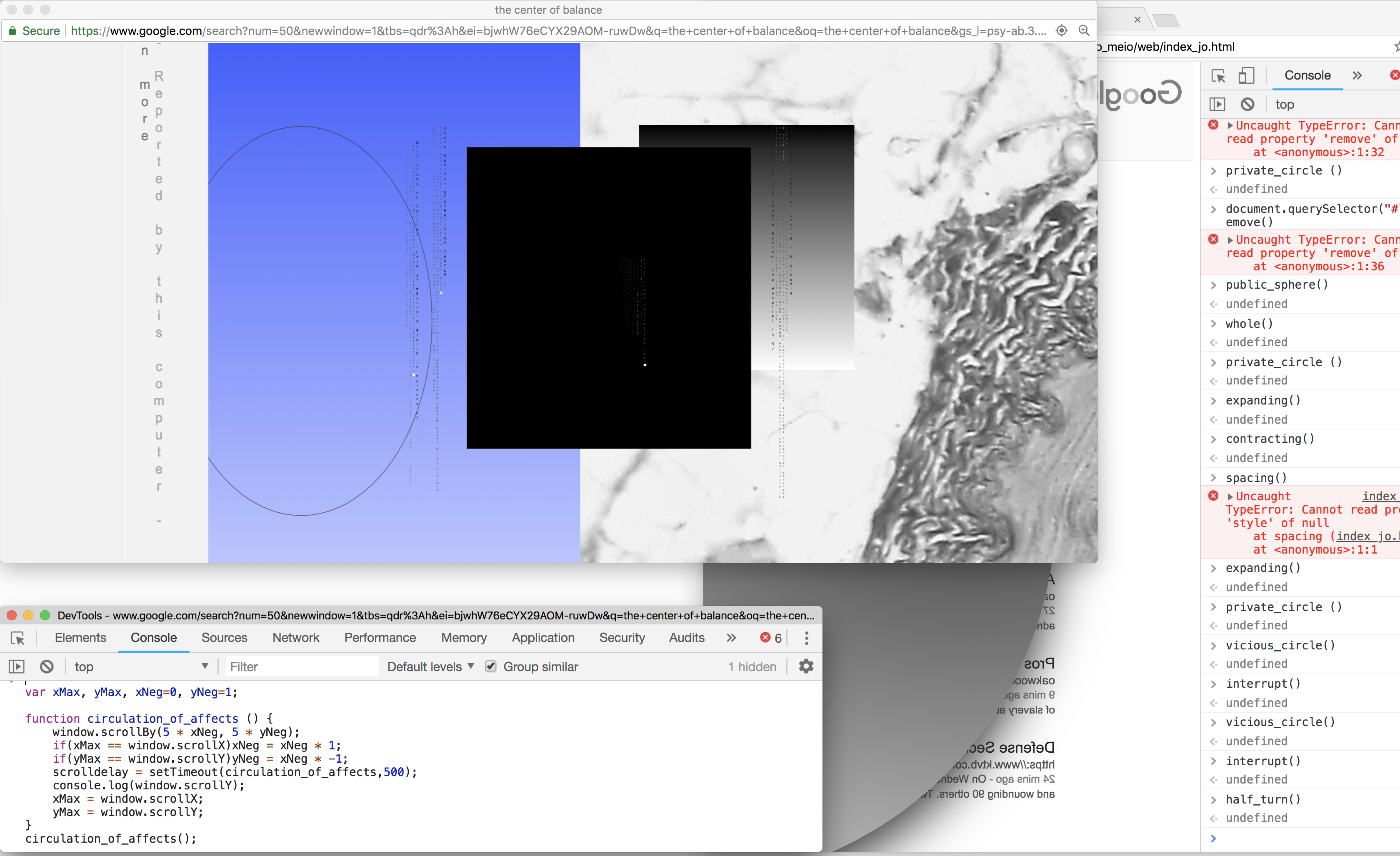

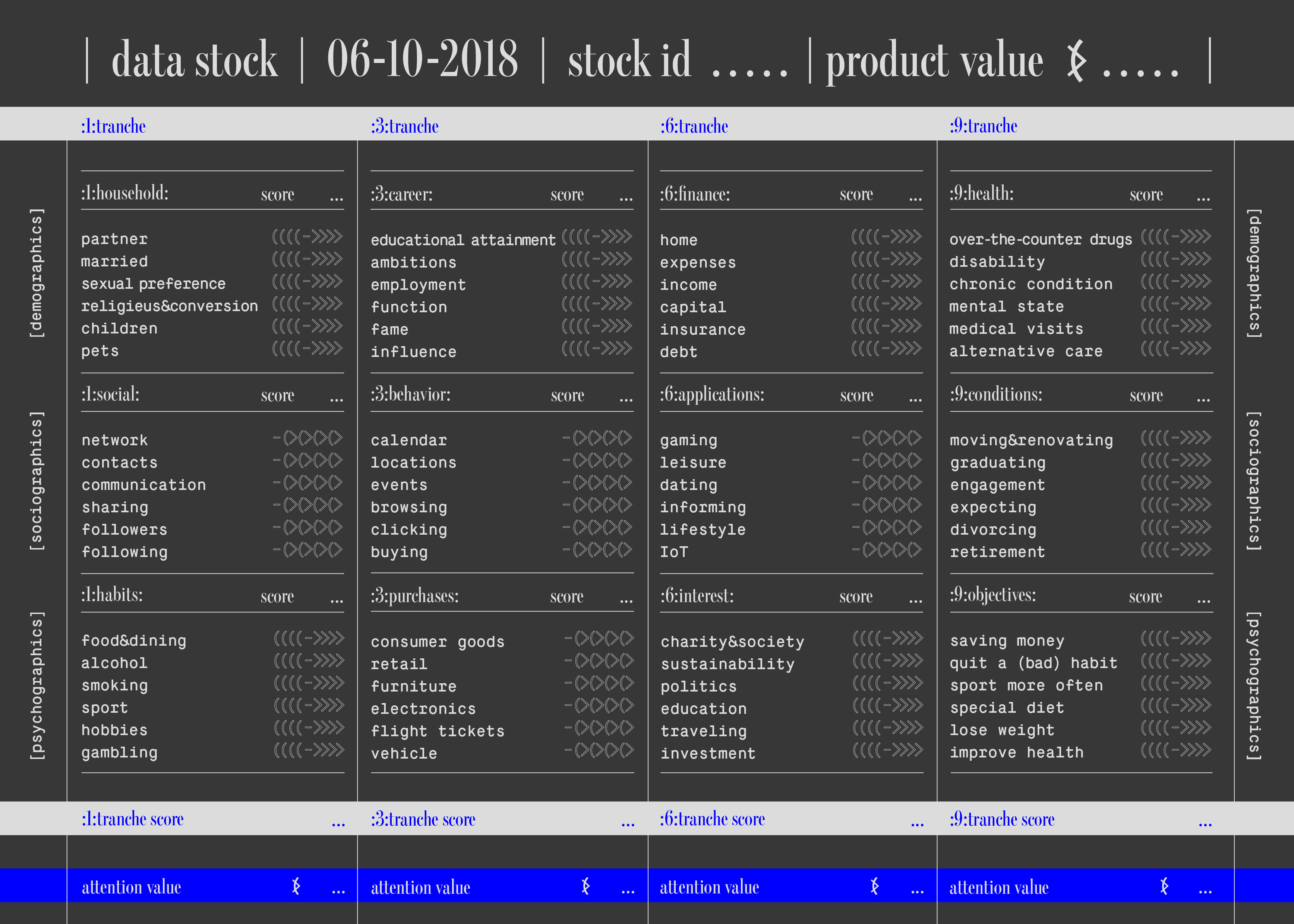

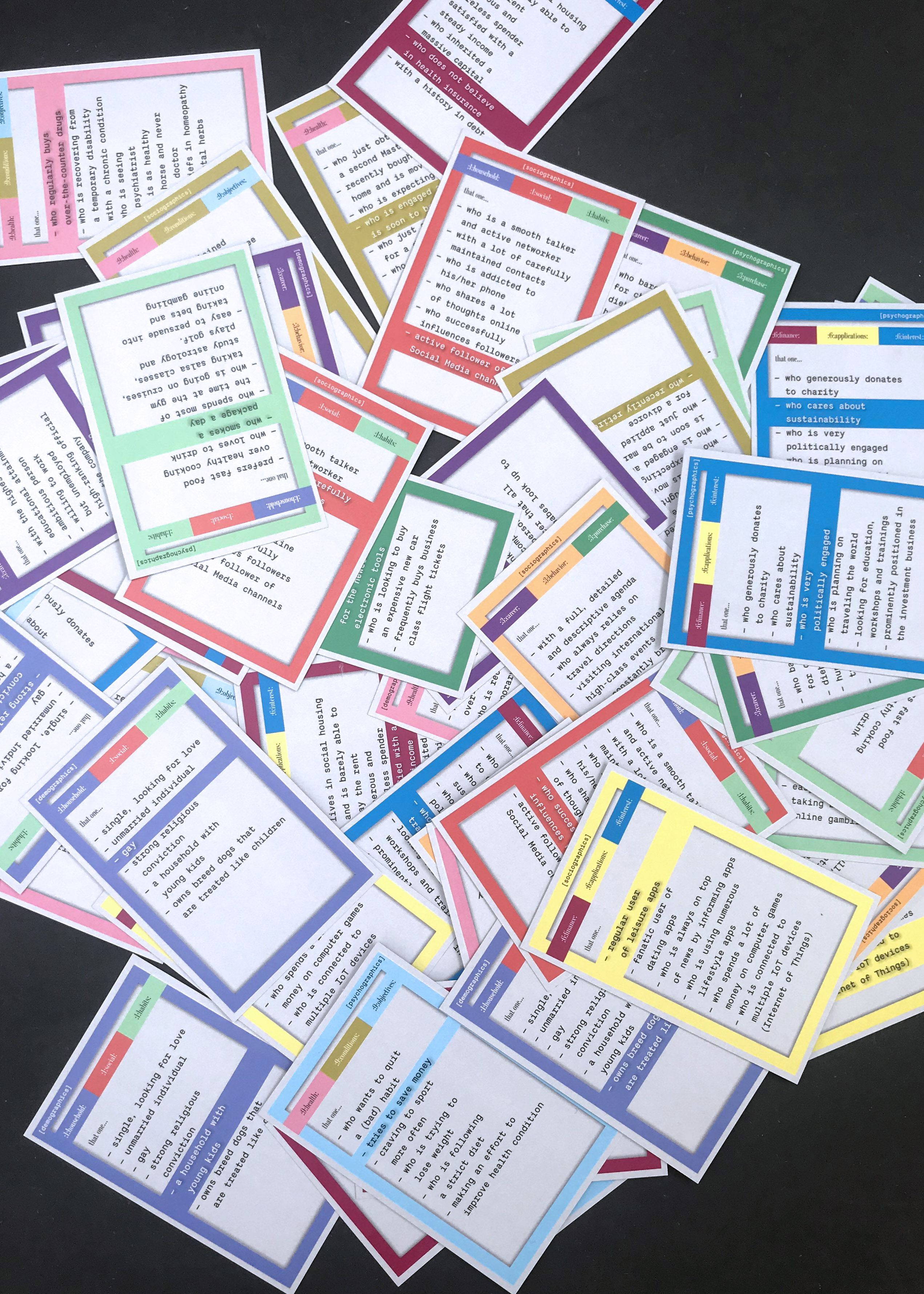

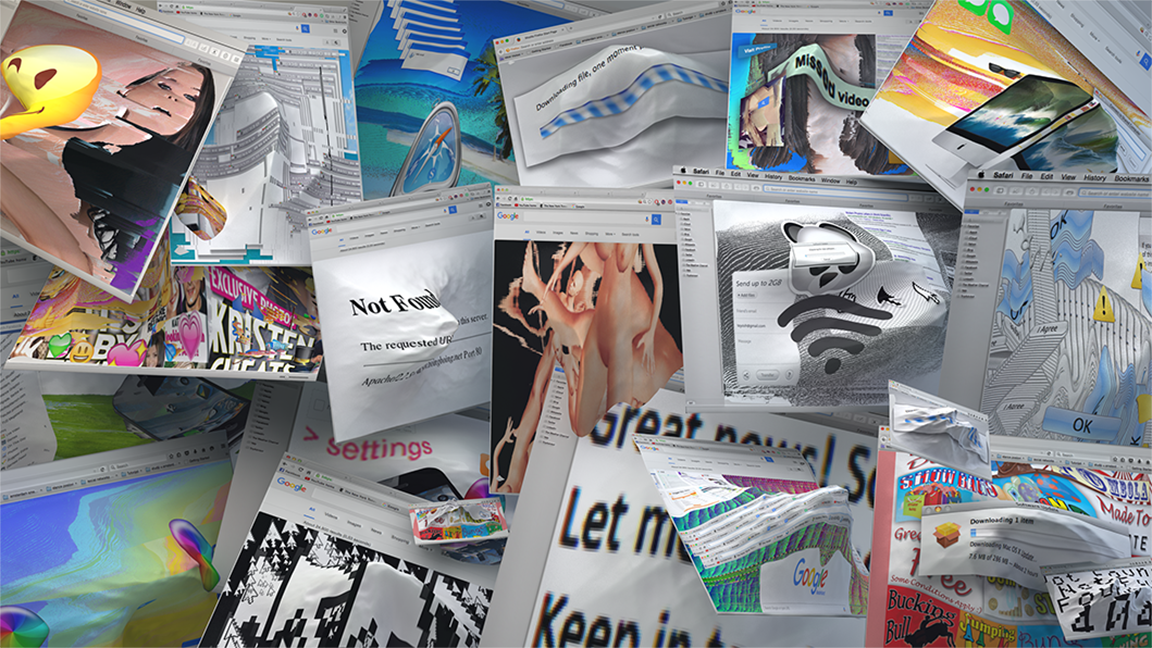

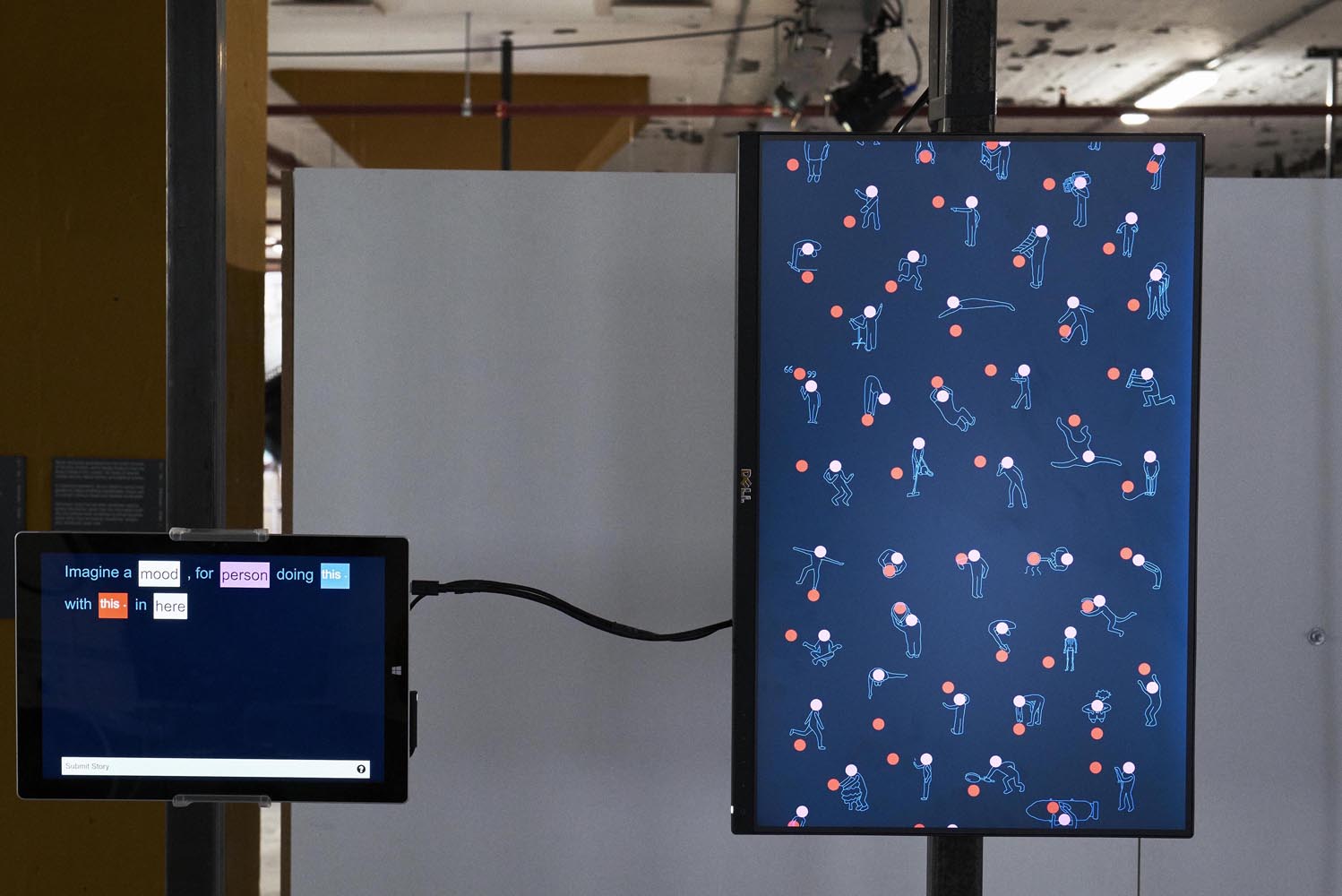

raise novel ethical dilemmas about privacy and employment. According to data designer Julia Janssen (2018 cohort), multiple times a day, we carelessly

dismiss warnings that state ‘I agree with the terms’ or ‘click here to continue’. But what do we actually permit? Who collects what data,

and above all, why? And what is the value of such information flows? Janssen’s project, 0.0146 Seconds (the time it takes to click on the ‘accept

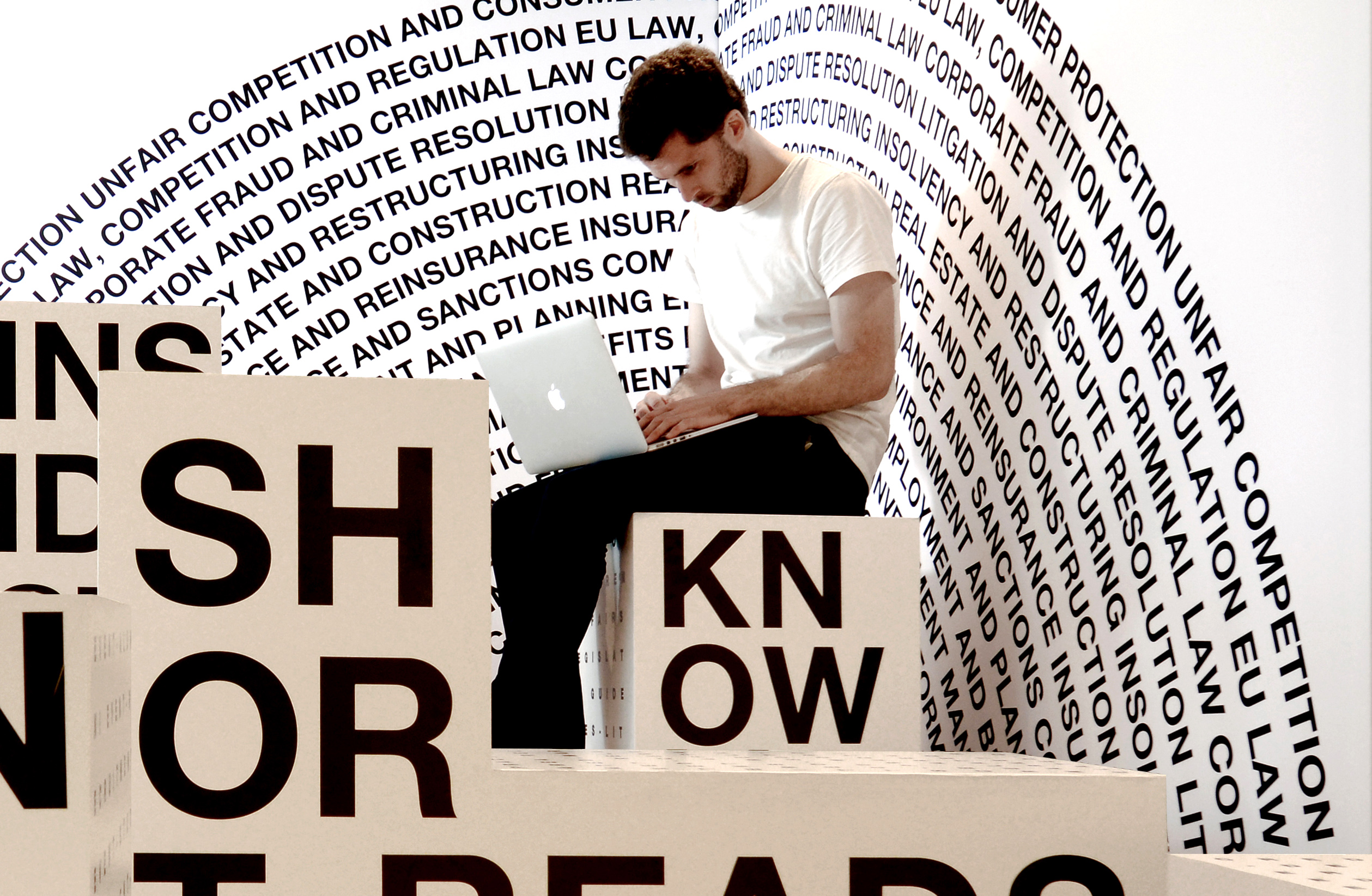

all’ button), informs us of the invisible economy behind the internet. She published all 835 privacy rules of the website for British tabloid the Daily Mail in a hefty tome. At events like the Dutch Design Week, the public reads this book aloud as a public indictment.

PROSECUTION AND DEFENSE

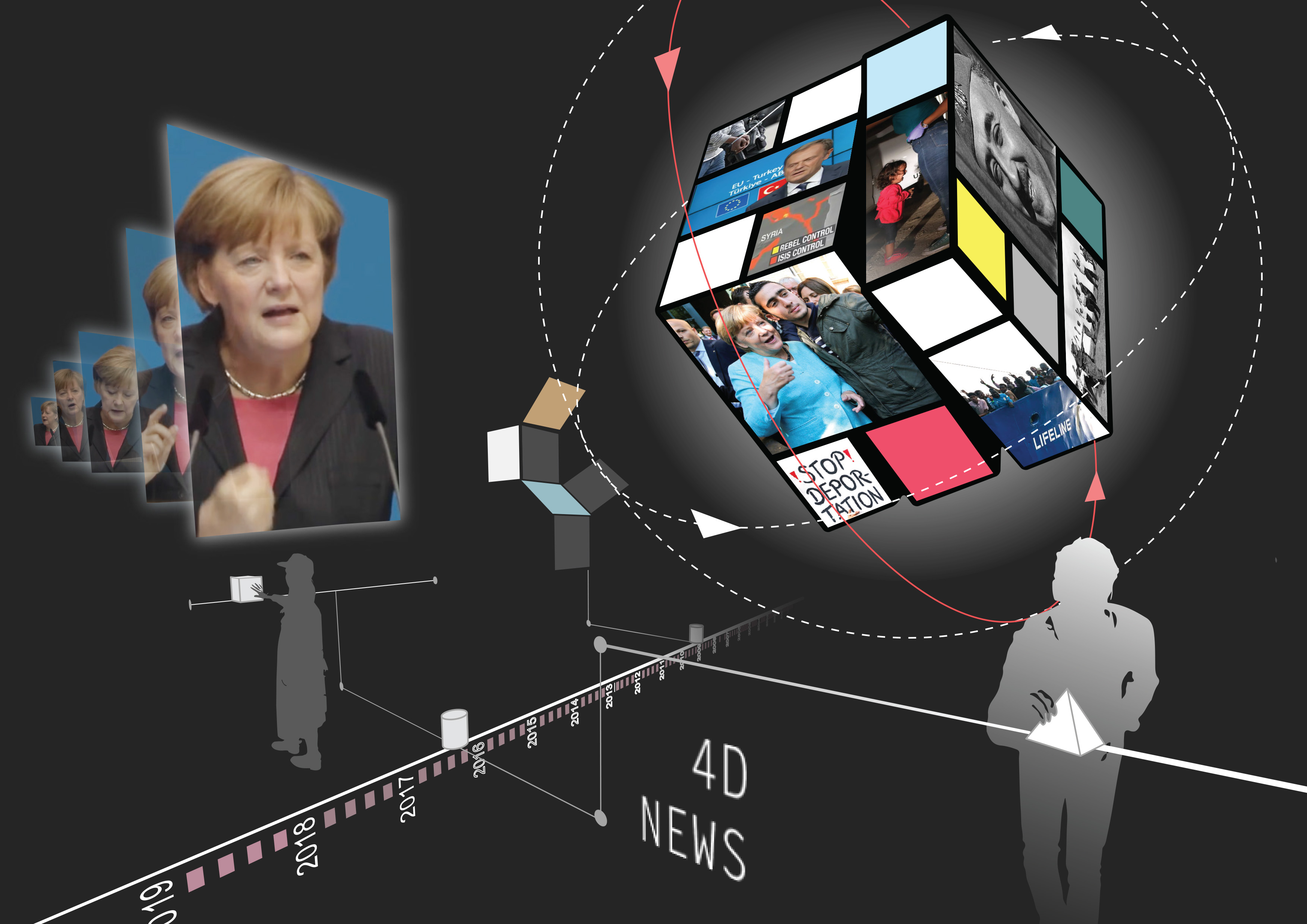

The new digital reality in which nothing is as it appears and fake news lurks everywhere pushes designers into the role of seeking the truth. To prevent complex

global issues, such as globalisation or climate change, from becoming bogged down in an abstract discussion, the design duo Cream on Chrome (Martina

Huynh and Jonas Althaus, 2020 cohort) used a fictitious lawsuit, without a trace of irony, to indict everyday objects. A sneaker is arrested and prosecuted for

climate change, and a face mask is put on trial for not being present in time to prevent contamination. Cream on Chrome uses this debate between prosecutor and

defence to question the mutual recriminations and the search for a scapegoat. In reality, are we not the ones who are actually on trial?

Cream on Chrome, Proxies on Trial

DESIGNING FOR URGENCY

Designers thus assume the role of the canary in the coal mine, warning us about the consequences of 15 September 2008, 12 December 2015 and 17 March 2018. The Talent

Development Scheme enables them to do this without the hindrance of a lack of time and money – and perhaps even more importantly, without the pressure of

quantifiable returns. Only free experimentation allows for unexpected insights. Who would have thought that Kuang-Yi Ku’s Tiger Penis Project could

have prevented a global pandemic if also applied to bats and pangolins? Or that the Daily Mail is no longer recognised by Wikipedia as a reliable news

source, as Julia Jansen already indicated?

Instead of conforming to the powers that be, designers take on the opportunity to transform the world; instead of imminent irreversibility, potential improvement

is nurtured. The world is explained and improved with speculative and practical, but always inventive, designs. This makes the Talent Development Scheme a valuable

resource for individual designers and society as a whole.

Text: Jeroen Junte

Longread Talent #3

Me and the other

Empathetic design talent focuses on people, not themselves (or things)

In the past seven years, the Creative Industries Fund NL has supported over 250 young designers with the Talent Development grant. In three longreads, we look for the shared mentality of this design generation, which has been shaped by the great challenges of our time. They examine how they deal with themes such as technology, climate, privacy, inclusiveness and health. In this third and final longread, the focus is no longer on personal success and individual expression but on ‘the other’.

The refugee crisis dominated 2015. Although people from Africa and Central Asia have been cast adrift by war, poverty and oppression for years, that summer, hundreds

of refugees on often makeshift boats and dinghies drowned in the Mediterranean. The impotence, anger, frustration, despair and sadness were aptly depicted in the

photo of the drowned three-year-old Syrian toddler Alan Kurdi’s body washed ashore on the Turkish coast. Where the financial crisis of 2008 was almost invisible

– indeed, even the bankers were at a loss – it was no longer possible to look away, not only in the media but also on the streets. The misery of the

other has become pervasive and omnipresent.

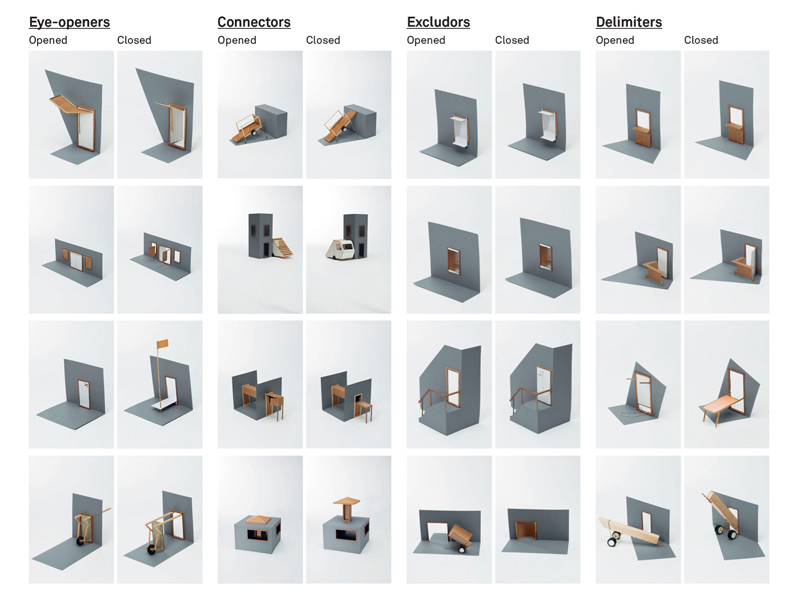

Asylum seeker centres in the Netherlands were full to overflowing. Designer Manon van Hoeckel (2018 cohort) saw the refugees in her neighbourhood

during her studies at the Design Academy Eindhoven. Realising she had never spoken to an asylum seeker, Van Hoeckel visited a squatted building that housed people

who had been rejected asylum. She saw these people were neither scammers nor pitiful, but rather powerful people who want to participate in and contribute to society

– precisely what this group was prohibited from doing. Out of concern and determination, Van Hoeckel devised a travelling embassy for undocumented asylum

seekers and migrants in limbo: unwanted in the Netherlands and their country of origin. The refugees, or ‘ambassadors’, could invite local residents,

passers-by and officials here for a conversation. The In Limbo Embassy facilitated meetings between local residents and a vulnerable group of newcomers.

EMPATHIC ENGAGEMENT

In many ways, Van Hoeckel’s attitude is typical of a generation that has benefitted from the Talent Development Scheme of the Creative Industries Fund NL for

the past seven years. Design is no longer about stuff but about people. This empathic enthusiasm now permeates all design disciplines. Personal success and individual

expression are no longer paramount. The designer, researcher and maker are categorically focused on the other. The 2015 refugee crisis has acted as both a particle

accelerator and a broadening of the profession because such humanitarian crises require unorthodox and radical proposals and ideas.

Urban planner Lena Knappers (2019 cohort) studied the spatial living conditions of asylum seekers, labour migrants and international students. As

part of her research at TU Delft, Rethinking the Absorption Capacity of Urban Space, she developed strategies to integrate migrants into the host society sustainably.

Too often, housing is temporary and informal, such as ad hoc container housing in the suburbs or vacant army barracks. Knappers researched alternative and more

inclusive forms of reception, focusing on the interpretation of public space. Ultimately, she has an even greater goal: an inclusive city in which all forms of inequality in public space are investigated and remedied.

The extent to which immigration has become part of the creative disciplines’ everyday reality is evident in the practice of Andrius Arutiunian (2021 cohort). After completing a master’s in Composition at the Royal Conservatory in The Hague, he focused on the tension between migration and new technologies.

In his development year, he studied the impact of displacement and dissent on society and how this impact can manifest itself in soundscapes. What does the integration

of newcomers to the Netherlands sound like? A common factor is the concept of gharib, which means ‘strange’ or ‘mysterious’ in

Arabic, Persian and Armenian. Arutiunian does not want to create specific encounters between people or pursue new forms of living. The cultural influence of migration

only serves to enrich his professional practice.

SINGLE FATHERS

Inclusivity and cultural diversity are now dominant societal issues. For example, the Black Lives Matter movement in the United States has fuelled intense debate

about institutional racism. The other is no longer a stranger to our borders and is our neighbour or colleague. Despite this, society threatens to become polarised,

marginalising demographic groups as a result. Designers actively engage in this discourse and apply design as an emancipating force for an all-inclusive society,

open and accessible to everyone, regardless of background.

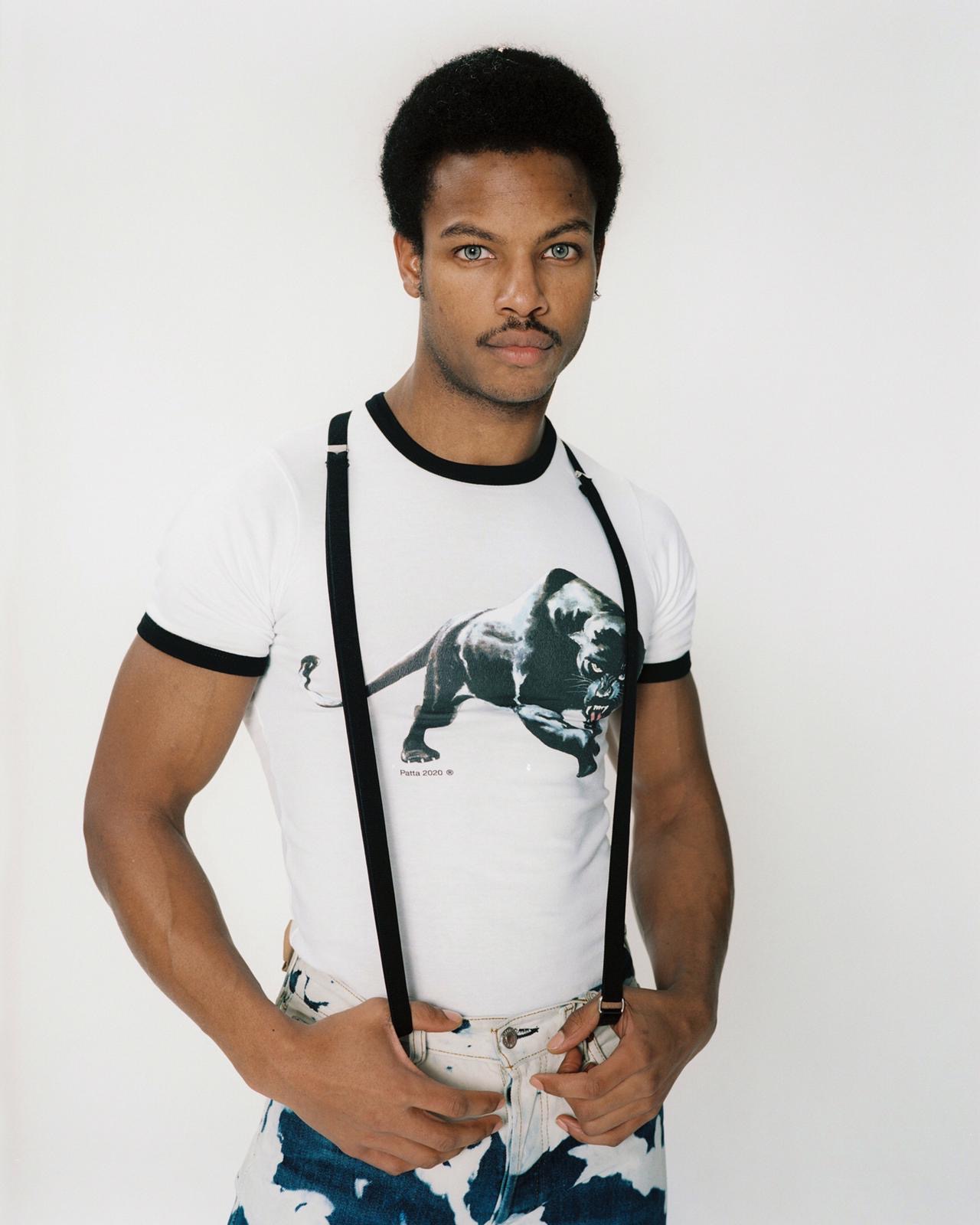

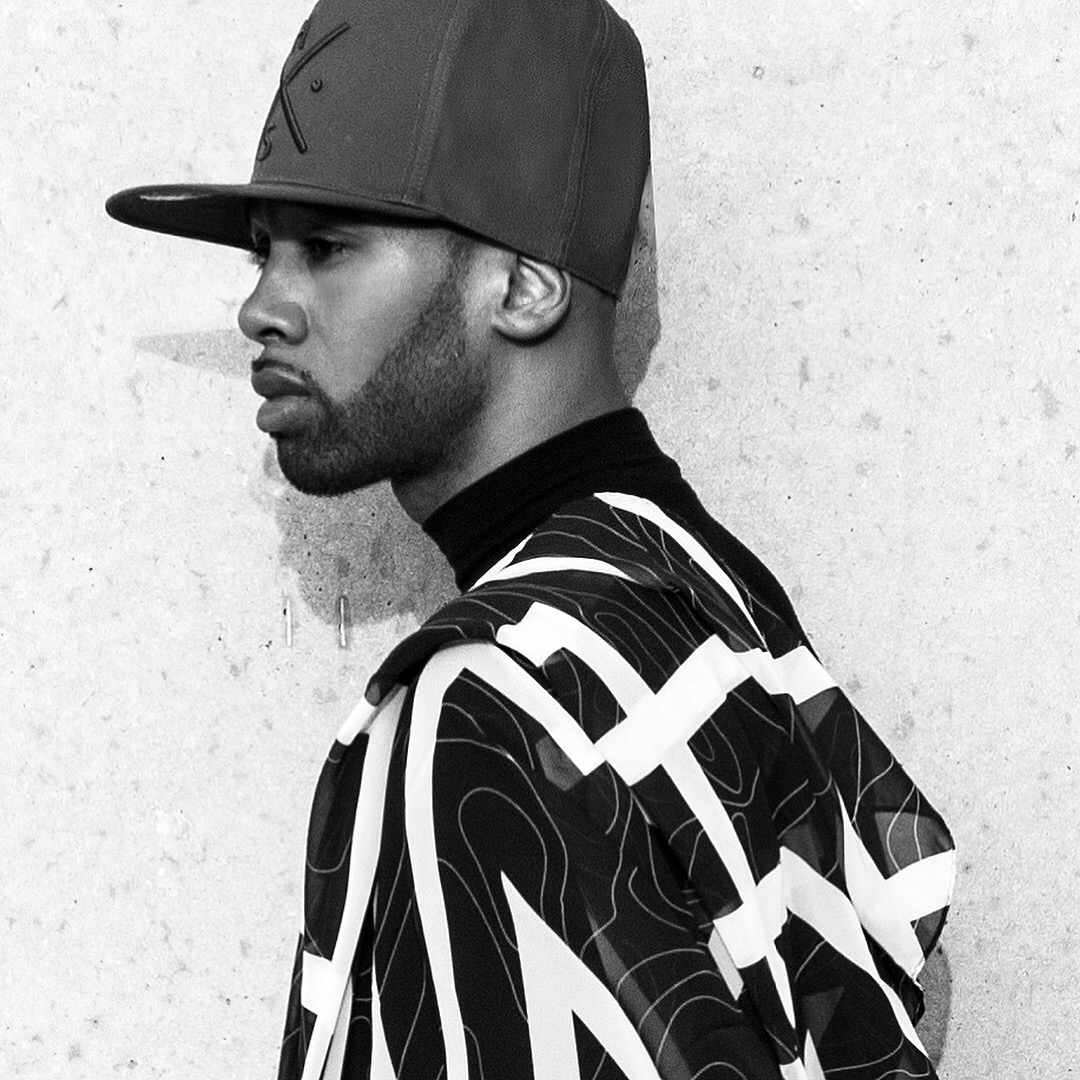

Giorgio Toppin, KABRA (XHOSA), Foto: Onitcha Toppin

The emancipation of disadvantaged groups starts with exploring and understanding a shared identity. Only by understanding one’s origins, culture and traditions

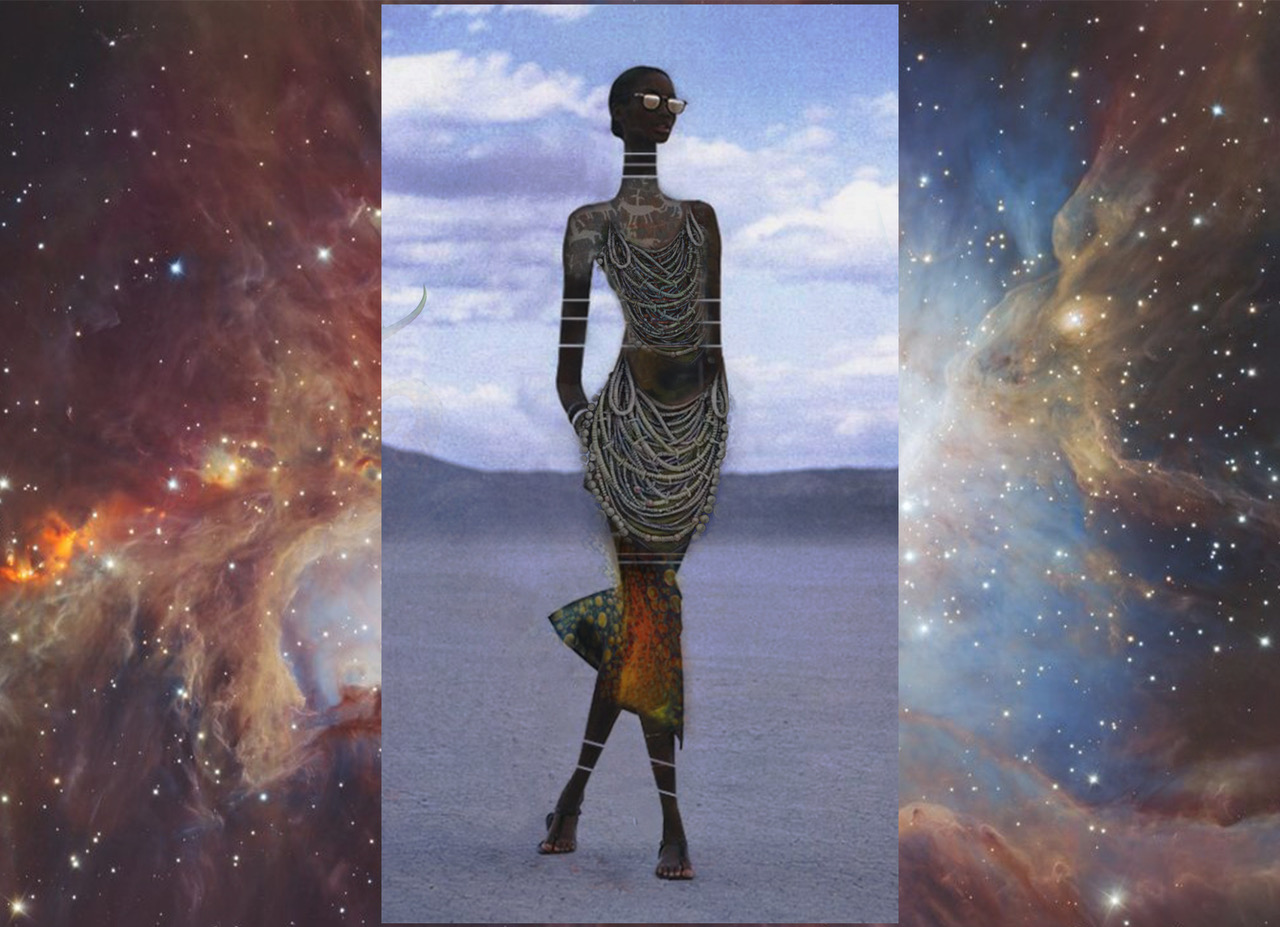

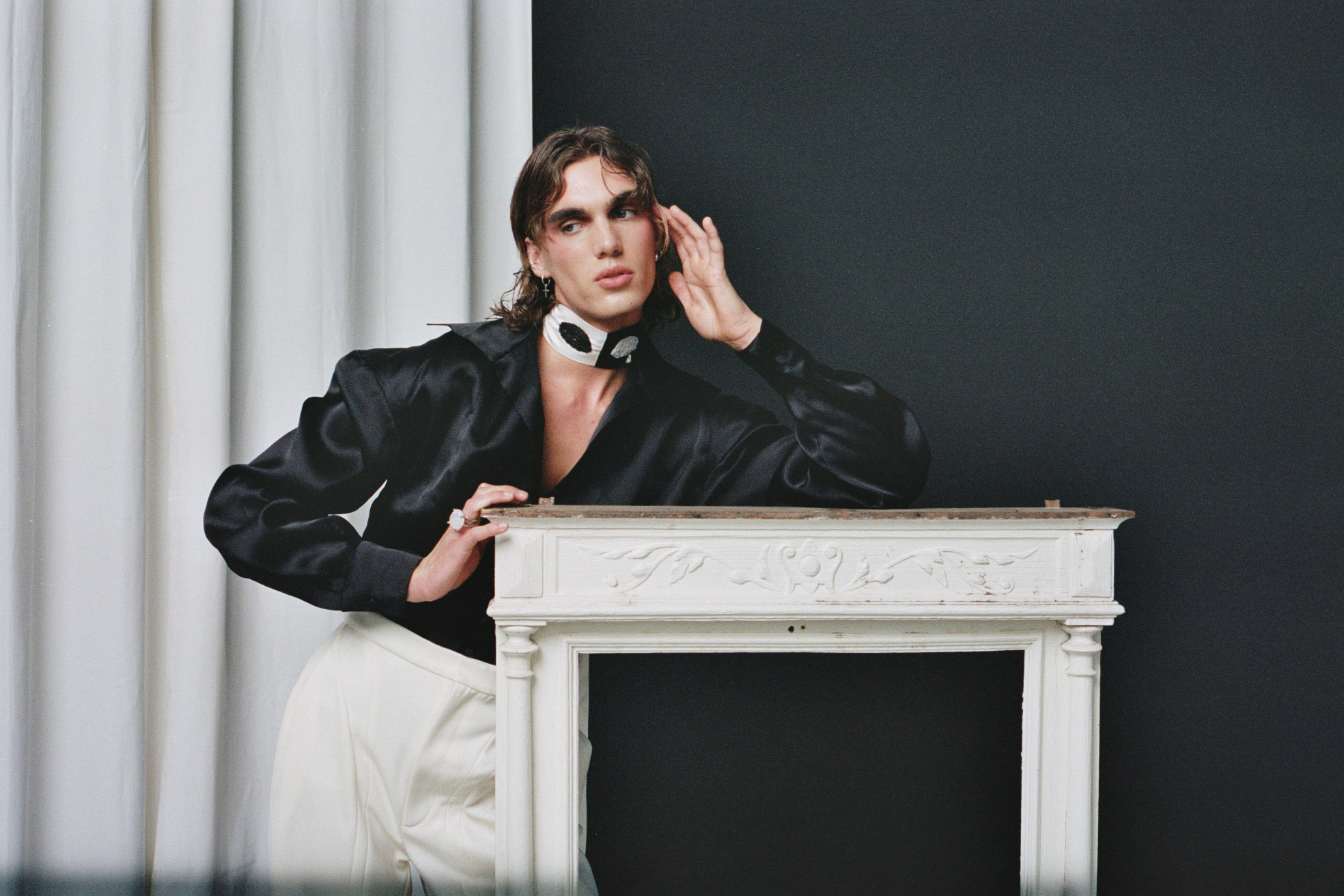

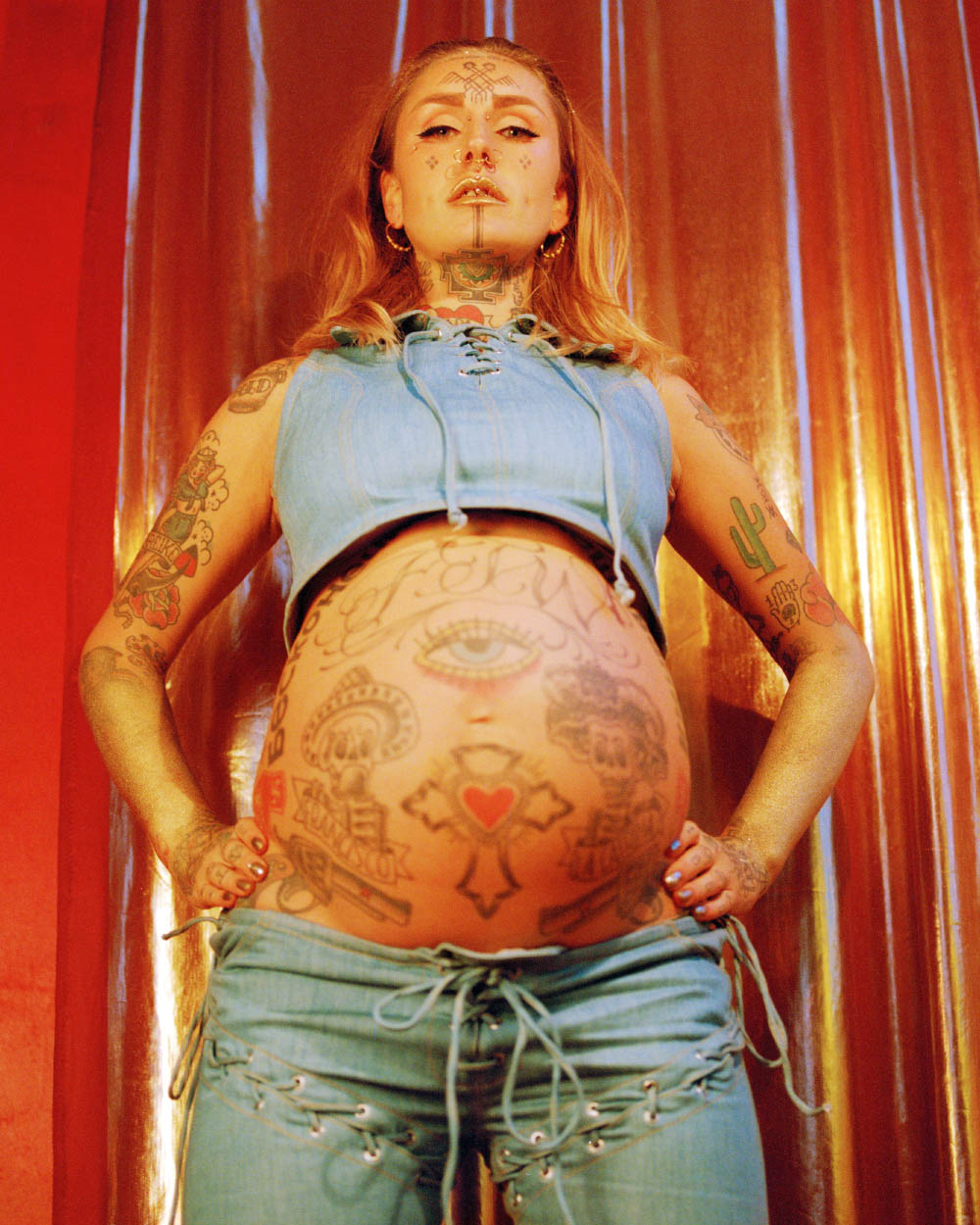

can one finally obtain a fully-fledged place in society. Giorgio Toppin (2020 cohort) is a proud Bijlmer-Amsterdammer and a Black man with a Surinamese

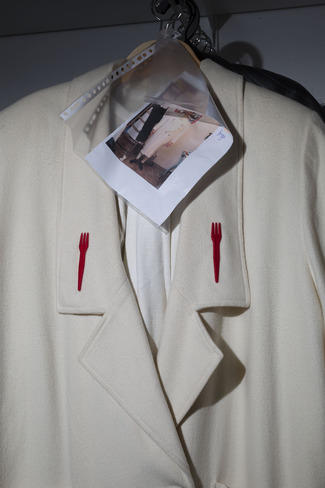

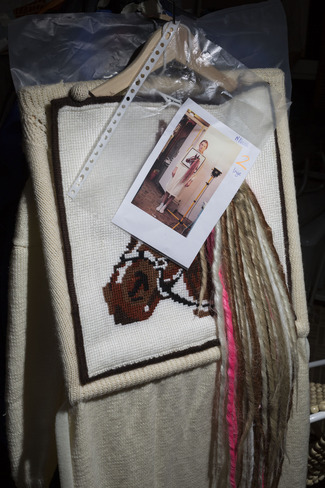

background. His Xhosa fashion label mixes these worlds into new stories, translating them into men’s clothing that fits within the contemporary Western context.

For the Surinamese diaspora narratives that inform his collections, he travelled to his native country to research and document local craftsmanship and traditional

production techniques. He then manufactured sweaters using indigenous knotting techniques and interpreted a winter coat using hand-embroidered traditional prints

from the Saramacca district. Conversely, he reimagined the Creole ‘kotomisi’, which is difficult to wear, with a comfortable and contemporary cut. Toppin’s

bicultural fashion strengthened the cultural identity of Surinamese people and thereby increased the understanding and appreciation for their origin among other

population groups. After all, Toppin insists his clothes must first and foremost be ‘cool to wear’.

Of course, creative disciplines have always been good at strengthening an identity. Fashion, functional objects, interiors and photographic images are simply excellent

means for showing who you are and especially who you want to be. In recent years, however, identity no longer signifies a non-committal lifestyle but can also be

a stigma that determines one’s social position. Identity is not always a choice, yet it has considerable influence on daily life – something to which

Surinamese, Turkish, Moroccan and Antillean Dutch people, up to the fourth generation, can testify. Any designer that examines fixed identities must be acutely

aware of cultural and emotional sensitivities. The designer who simply explains what is right and wrong lags behind the inclusive facts.

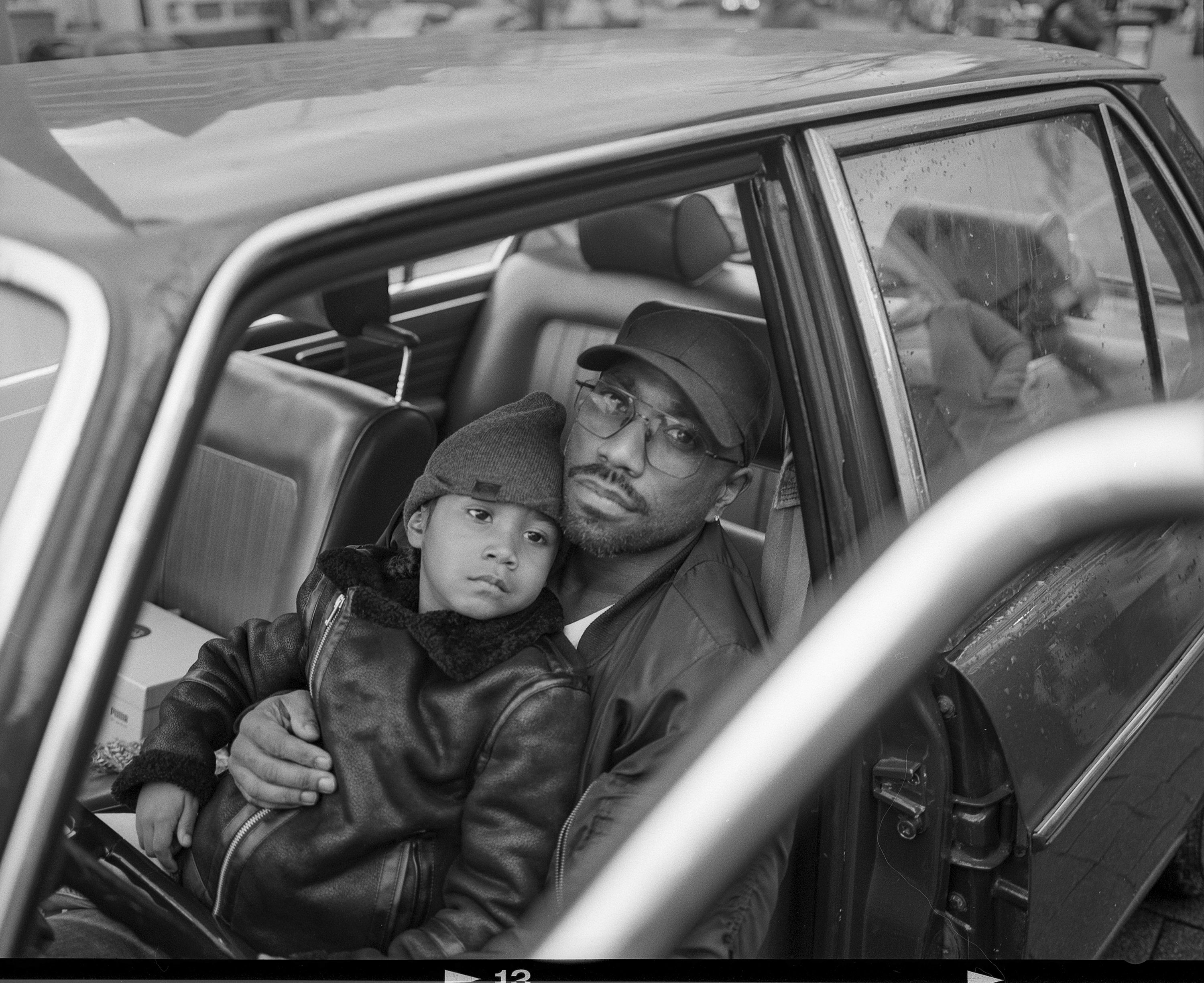

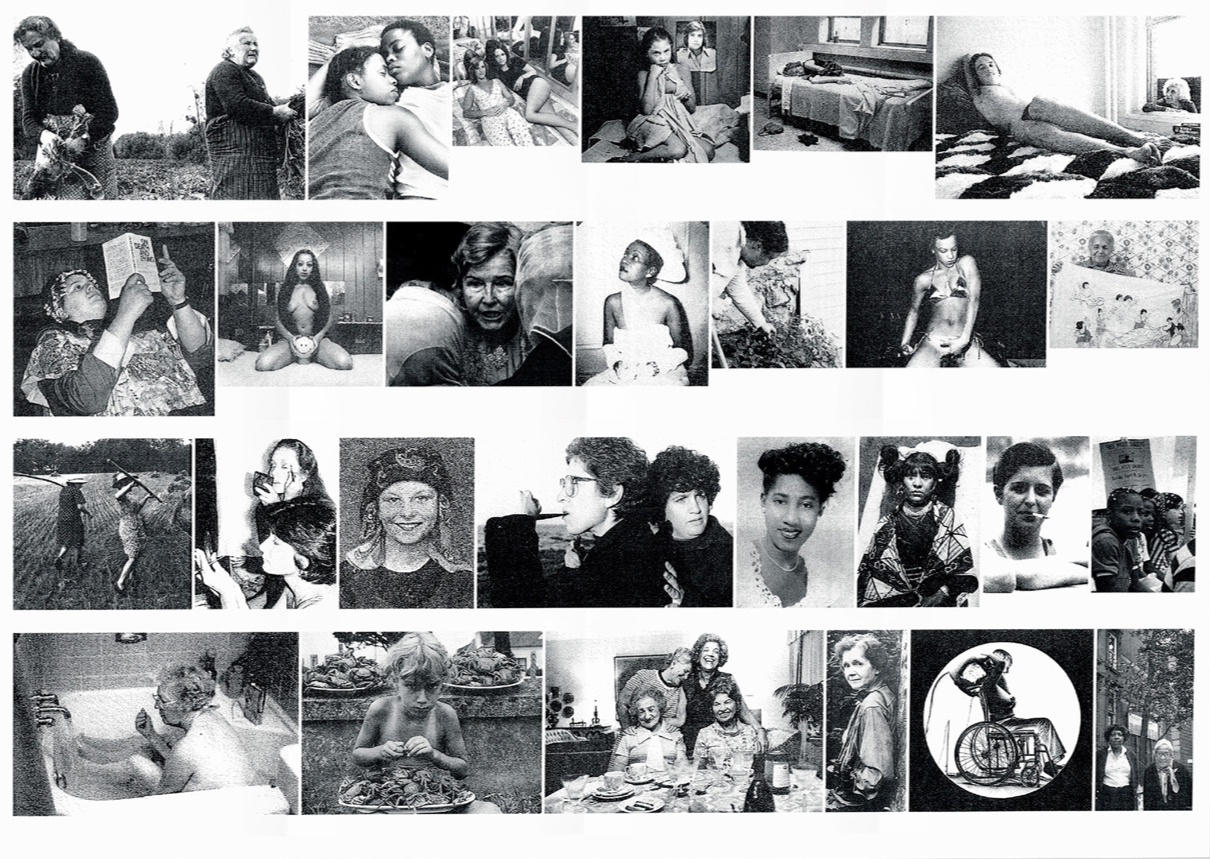

Marwan Magroun, The Life of Fathers, Adison & Ayani

Consequently, designers increasingly work from a position of personal involvement or agency (ownership). Photographer and storyteller Marwan Magroun (2020 cohort) captured the world of single fathers with a migrant background in his documentary project The Life Of Fathers. Magroun, who grew up without

a father figure for most of his childhood, sought answers to and stories of an often unnoticed but deeply felt fatherhood. He wanted to dispel the notion that fathers

from a migrant background are not involved in parenting. His photographic report and accompanying film (now broadcast on NPO3) has given a group of devoted but

underestimated fathers a voice and a face.

QUEERS AND EXTENDED FAMILIES

Diversity is embraced and propagated throughout society. Prevailing views on gender, sexuality and ethnicity are shifting. This also means plenty of playing and

experimentation with identity and how it can be designed. As a result, designers are no longer a conduit for industry or government but adopt an activist stance.

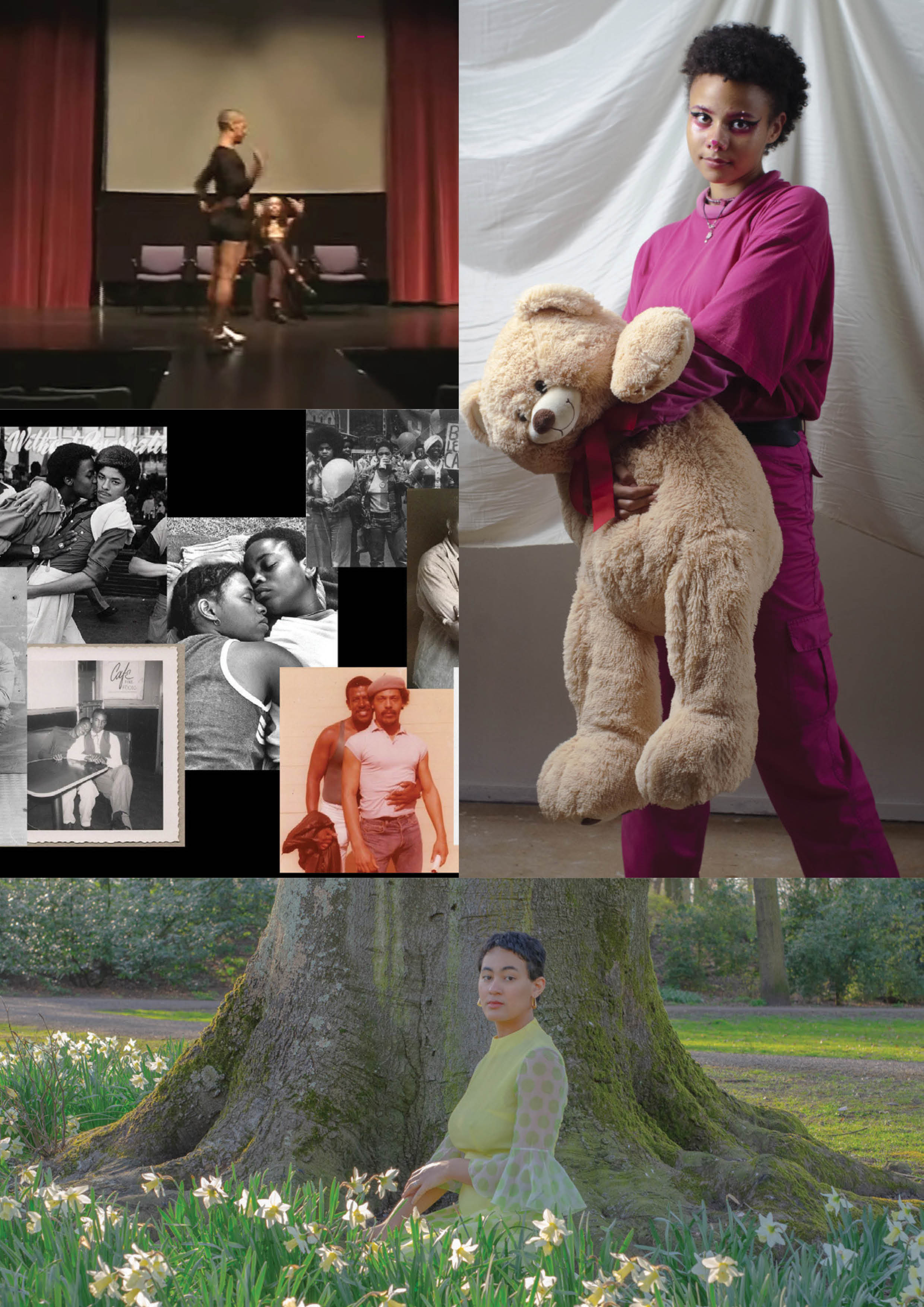

The guiding principle is social cohesion and no longer one’s ego. Renee Mes (2021 cohort) wanted to dismantle the stereotyping of the LGBTQ+

community and thereby increase acceptance. She focused specifically on how extended families are shaped within the various queer communities. This self-selected

family is often built as an alternative to the rejection or shame from the families in which queers were raised. But this new lifestyle struggles with legal, medical,

educational and other institutional disadvantages. Mes’s approach was that was make being seen the first step toward recognition.

For her research and film portraits, Mes, who is white cisgender, worked with the organisation Queer Trans People of Colour. Collaboration can also generate agency.

Besides, whose identity is being addressed? Or, to use the terminology of Black Lives Matter, ‘nothing about us without us’. It is logical – and

maybe even necessary – that inclusive design is realised according to these politically correct rules of agency and representation. Indeed, the countless

cultural sensitivities demand great care.

SELECTION AND SCOUTING

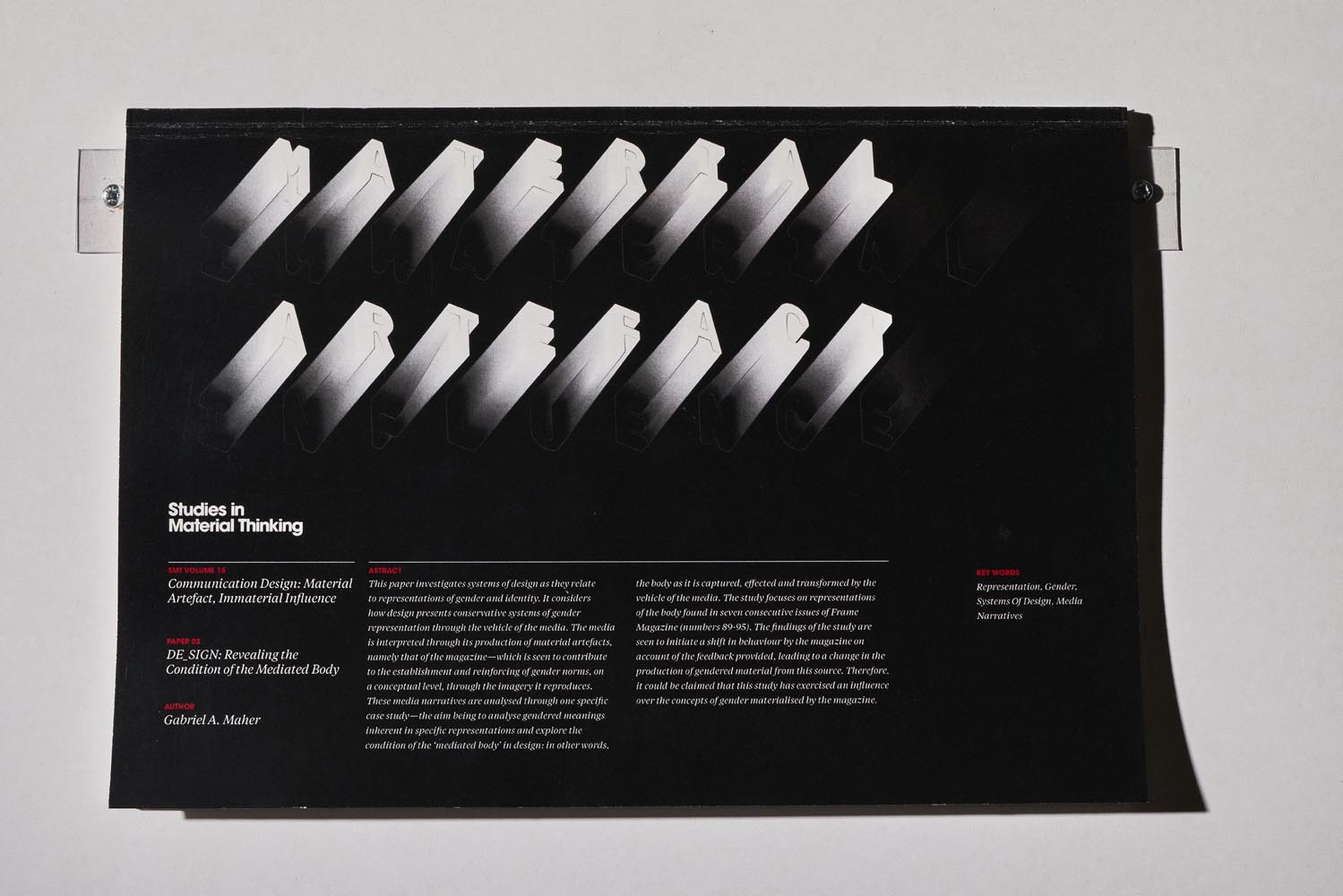

The creative industries are not exempt from equal opportunities. The design disciplines are not free from stereotypes. The Mediated Bodies research project

by Gabriel A. Maher (2016 cohort) meticulously maps the gender relationships in the international design magazine Frame. Eighty per cent

of the people in the magazine were male – from the designers interviewed to the models in the advertisements. Moreover, women were mainly portrayed in role-confirming

and sometimes even submissive positions, such as bending over or crouching down. Maher’s feminist practice seeks to ‘deconstruct’ the design discipline

to identify the existing power structure and prejudices. Only after an active process of self-reflection and criticism can design fulfil its potential as a discipline

that contributes to societal improvement.

However, attention to polyphony alone is insufficient. Representation should be proportional, especially in the creative disciplines. The Talent Development Scheme

actively contributes to this balance with new forms of selection. Scout nights are available for designers, researchers and makers who have developed professionally

in practice, without a formal design training. During these evenings, talented designers who work outside the established creative channels can pitch their work

to a jury. Many designers who use these scout nights belong to minority groups for whom going to an art academy or technical university is less established.

The self-taught Rotterdam photographer Khalid Amakran (2021 cohort) has developed from hobbyist to professional portrait photographer. After selection

during a scout night, he devoted a year to a project about the identity formation of young second and third-generation Moroccan Dutch people. Amakran’s 3ish project comprises a book and short documentary detailing this group’s struggles with loyalty issues, code-switching, institutional racism, jihadism, and Moroccan

Dutch males’ politicisation. Representing emerging talents from bicultural or non-binary backgrounds is imperative for the creative industries. Only visible

examples and recognisable role models can create a feeling of recognition and appreciation and guarantee the diversity necessary for the creative industries.

ARAB CALLIGRAPHY

The scout nights have selected nine talented practitioners for the 2020 and 2021 cohorts. This number will undoubtedly increase in the coming years. An added value

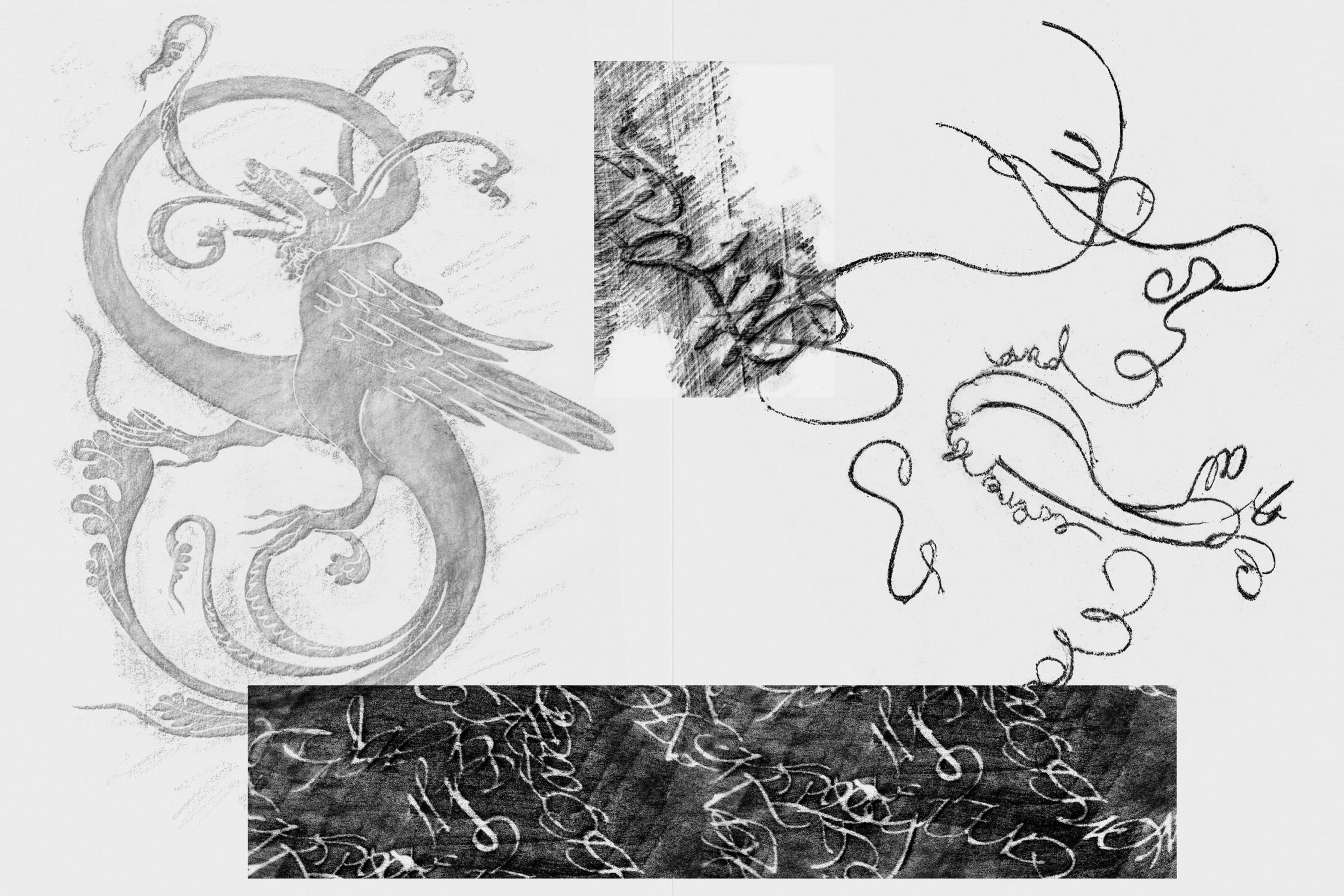

is that these designers are growing the diversity of content in their field through their singular professional practices. Another self-taught recipient is ILLM,

the alias of illustrator Qasim Arif (2021 cohort). He mixes the age-old craft of calligraphy with contemporary elements of hip-hop and street culture.

Traditional Arabic calligraphy is, by definition, two-dimensional because, according to Islamic regulations, the sculpting of living beings is reserved for Allah.

ILLM wants to convert this visual language into sculptures. He also draws inspiration from his own life. He grew up in a metropolis as a third-generation Moroccan

Dutch citizen, which informs his mix of calligraphy with pop-cultural icons like the Nike Air Max 1, a recognisable status symbol representing the dreams, wishes

and memories of many children from migrant backgrounds. ILLM merges street culture and age-old graphic craftsmanship into a completely new idiom.

DRIVERS OF INCLUSION

The Talent Development Scheme is a necessary social empowerment that naturally coincides with an activist attitude. A sincere and profound commitment to identity

and inclusivity guides designers, researchers and makers. Through a capacity for empathy and sensitivity – either innately or through collaboration with the

target group – they can catalyse transformative initiatives and constructive debate. This capacity unlocks the creative disciplines’ powerful potential:

the realisation of a diverse society in which all sections of society are equal. After all, looking at the other ultimately means looking at us all.

Text: Jeroen Junte

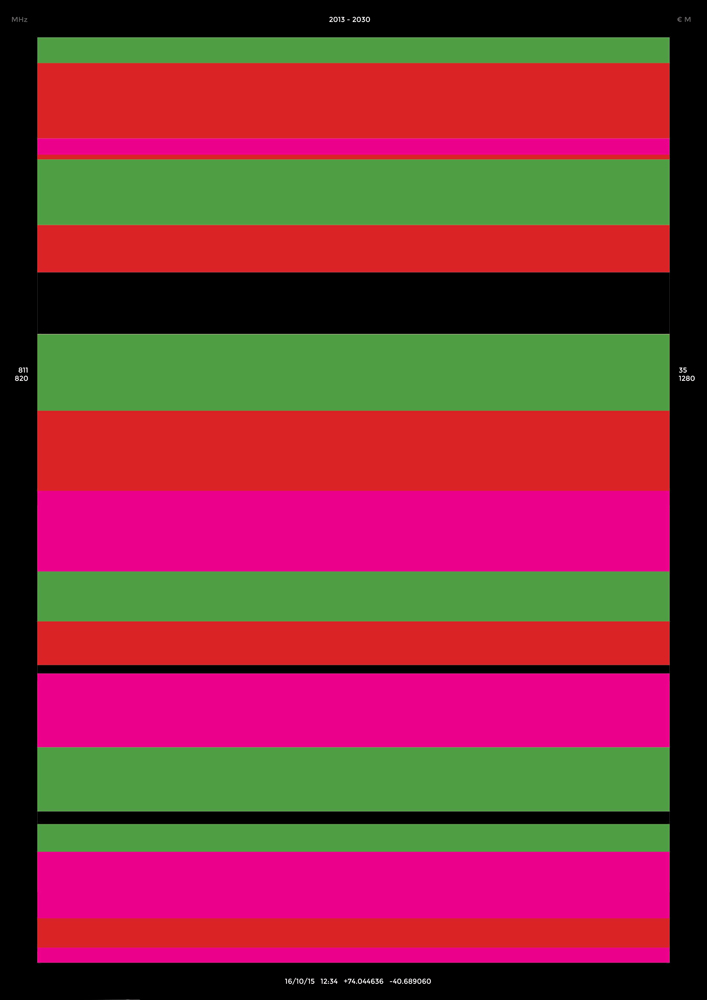

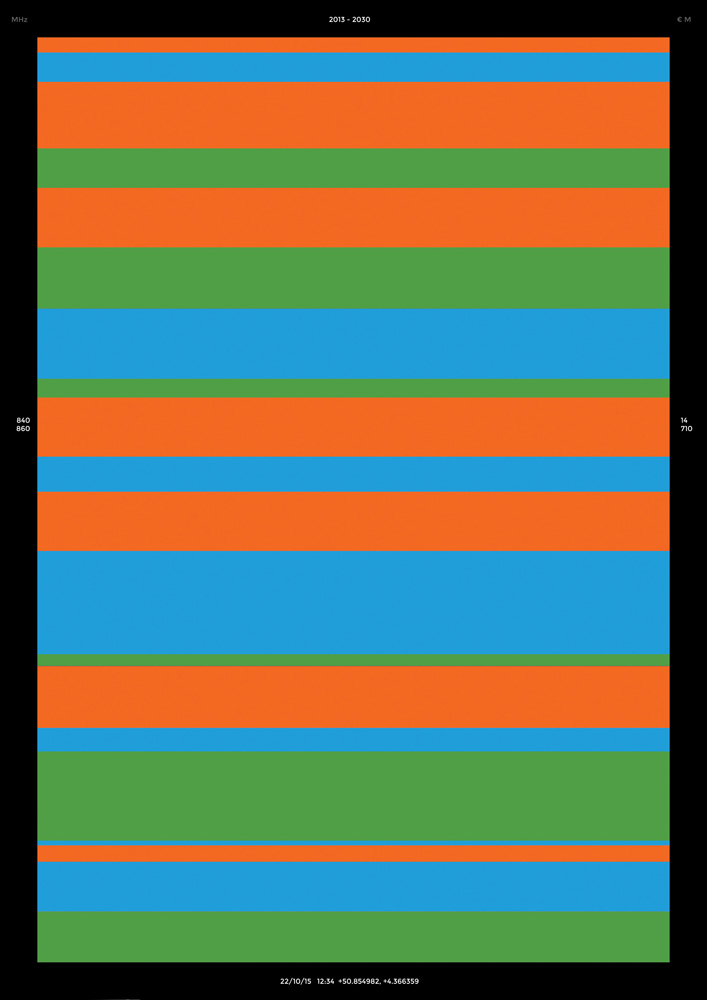

Diamons Investment & the New Oil

by Rosa te Velde

Around 1960, Dutch television broadcast its first talent show, a concept imported from America. ‘Nieuwe

Oogst’ (New Harvest) was initially made in the summer months on a small budget. It turned out that talent

shows were a cheap way of making entertaining television: participants seized the opportunity to become

famous by showcasing their tricks, jokes, creating entertainment and spectacle — in return for coffee and

travelling expenses.1

Talent shows have been around since time immemorial, but the concept of talent development

— the notion of the importance of financial support and investment to talent — is relatively new. Since the

rise of the information society and knowledge economy in the 1970s, the notion of ‘lifelong learning’ has

become ever more important. Knowledge has become an asset. Refresher courses, skill development and

flexibility are no longer optional, and passion is essential. You are now responsible for your own happiness and

success. You are expected to ‘own’ your personal growth process. In 1998, McKinsey & Company published

‘The War for Talent’. This study explored the importance of high performers for companies, and how to

recruit, develop and motivate talented people and retain them as employees. In the past few decades, talent

management has become an important element in companies’ efforts to maximise their competitiveness,

nurture new leaders or bring about personal growth. Sometimes, talent management is aimed at the company

as a whole, but it is more likely to focus on young, high-potential employees who either are already delivering

good performances or have shown themselves to be promising.2

It was social geographer Richard Florida who made the connection between talent and

creativity, in his book ‘The Rise of the Creative Class’ (2002). In this book, he drew the — irreversible — link

between economic growth, urban development and creativity. A hint of eccentricity, a bohemian lifestyle

and a degree of coolness are the determining factors for ‘creativity’ that provide space for value creation.

His theory led to a surge in innovation platforms, sizzling creative knowledge regions and lively creative hubs

and breeding grounds. The talent discourse became inextricably linked with the creative industry. The Global

Creativity Index, for instance, set up by Florida (in which the Netherlands was ranked 10th in 2015), is based

on the three ‘Ts’ of technology, talent and tolerance. The talent phenomenon really took off in the world of

tech start-ups, with innovation managers fighting for the most talented individuals in Silicon Valley. ‘Talent is

the new oil’.

The idea that talent can grow and develop under the right conditions is diametrically opposed

to the older, romantic concept of a God-given, mysterious ‘genius’. The modern view sees talent as not

innate (at least, not entirely so), which is why giving talent money and space to develop makes sense. Like the

Growing Diamond (groeibriljant), the Dutch diamond purchase scheme in which diamonds can become ‘ever

more valuable’.

What is the history of cultural policy and talent development in the Netherlands? Whereas

before the Second World War the state had left culture to the private sector, after the war it pursued an

active ‘policy of creating incentives and setting conditions’.3 The state kept to the principles of Thorbecke

and did not judge the art itself.4 But literary historian Bram Ieven argues that a change took place in the 1970s.

It was felt art needed to become more democratic, and to achieve that it needed to tie in more with the

market: “[…] from a social interpretation of art (art as participation), to a market-driven interpretation of the

social task of art (art as creative entrepreneurship).”5 The Visual Artists’ (Financial Assistance) Scheme (BKR)

and later the Artists’ Work and Income Act (WWIK) gave artists and designers long-term financial support if

they did not have enough money, provided they had a certificate from a recognised academy or could prove

they had a professional practice.6

It was Ronald Plasterk’s policy document on culture, ‘The Art of Life’ (2007), that first

stressed the importance of investing in talent, as so much talent was left ‘unexploited’.7 Plasterk called in

particular for more opportunities to be given to ‘outstanding highly talented creatives’, mainly so that the

Netherlands could remain an international player. Since then, ‘talent development’ has become a fixture in

cultural policy. Halbe Zijlstra also acknowledged the importance of talent in ‘More than Quality’ (2012), but he

gave a different reason: ‘As in science, it is important in culture to create space for new ideas and innovation

that are not being produced by the market because the activities in question are not directly profitable.’8

This enabled the support for talent to be easily justified from Zijlstra’s notoriously utilitarian perspective with

its focus on returns, even after the economic crisis. Jet Bussemaker also retained the emphasis on talent

development, and talent is set to remain on the agenda in the years ahead.9

The Creative Industries Fund NL first gave grants to a group of talented creatives in 2013. As

in the Mondrian Fund’s talent development programme, the policy plan for 2013–2016 opted for a single, joint

selection round each year. While the emphasis was on individual projects, it was noted that a joint assessment

would be more objective and professional and that this would facilitate the accompanying publicity.10

Who is considered a possible talented creative? To be eligible for a grant, you have to

satisfy a number of specific requirements: you have to be registered with the Chamber of Commerce, have

completed a design degree less than four years ago and be able to write a good application that persuades

the nine committee members from the sector that you have talent. Based on the application, they decide

how much potential, or promise, they see in your development, taking into account the timing of the grant for

your career. While there are many nuances in the application process, these factors make sure the concept

of ‘talent’ is clearly defined.

If you get through the tough selection process — on average ten to fifteen per cent of the

applications result in a grant — you enjoy the huge luxury of being able to determine your own agenda for

an entire year, of being able to act instead of react. It seems as if you have been given a safe haven, a short

break from your precarious livelihood. But can it actually end up reinforcing the system of insecurity? What

should be a time for seizing opportunities may also lead to self-exploitation, stress and paralysis. In practice,

the creative process is very haphazard. Will the talented creatives be able to live up to their promise?

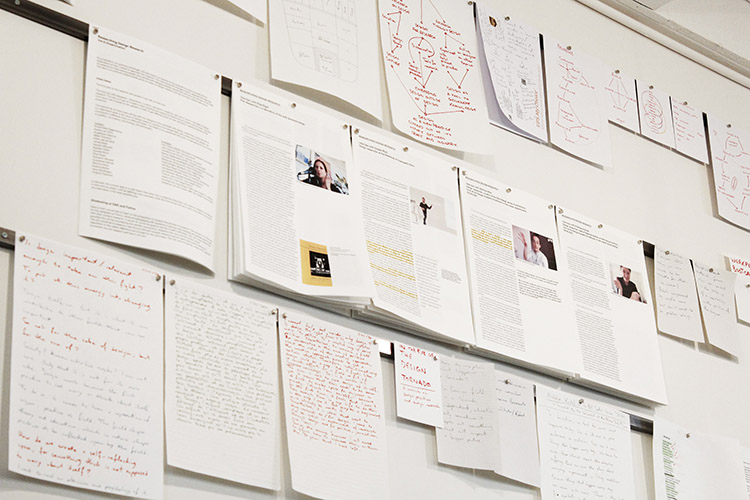

One of them went on a trip to China, another was able to do a residency in Austria, while yet

another gave up their part-time job. Many have carried out research in a variety of forms, from field studies

and experiments with materials to writing essays. Some built prototypes or were finally able to buy Ernst

Haeckel’s ‘Kunstformen der Natur’. Others organised meetings, factory visits, encounters, interviews and

even a ball.

Is there a common denominator among the talented creatives who were selected? As in

previous years, this year the group was selected specifically to ensure balance and diversity — encompassing

a sound artist, a filmmaker, a design thinker, a researcher, a cartographer, a storyteller, a former architect

and a gender activist-cum-fashion designer. Given the diversity of such a group, a joint presentation may feel

forced. But presenting them to the outside world as a group enhances the visibility of these talented people,

and this is important, because how else can the investment be vindicated?

These are the questions that the Creative Industries Fund NL has been debating ever since

the first cohort: how to present this group without the presentation turning into a vulgar, unsubtle spectacle

or propagating a romantic notion of talent, and at the same time, how to show the outside world what is

being done with public money. And what would benefit the talented individuals themselves? In the past few

years, various approaches have been tested as ways of reflecting on the previous year, from various curated

exhibitions with publications and presentations to podcasts, texts, websites, workshops and debates.

The Creative Industries Fund NL operates as a buffer between neoliberal policy and the

reality of creativity. The fund provides a haven for not-yet-knowing, exploration, making, experimentation

and failure, without setting too many requirements. It is a balancing exercise: how do you tone down the

harsh language of policy and keep at bay those who focus only on returns on investment, while still measuring

and showing the need for this funding, and thereby safeguarding it?

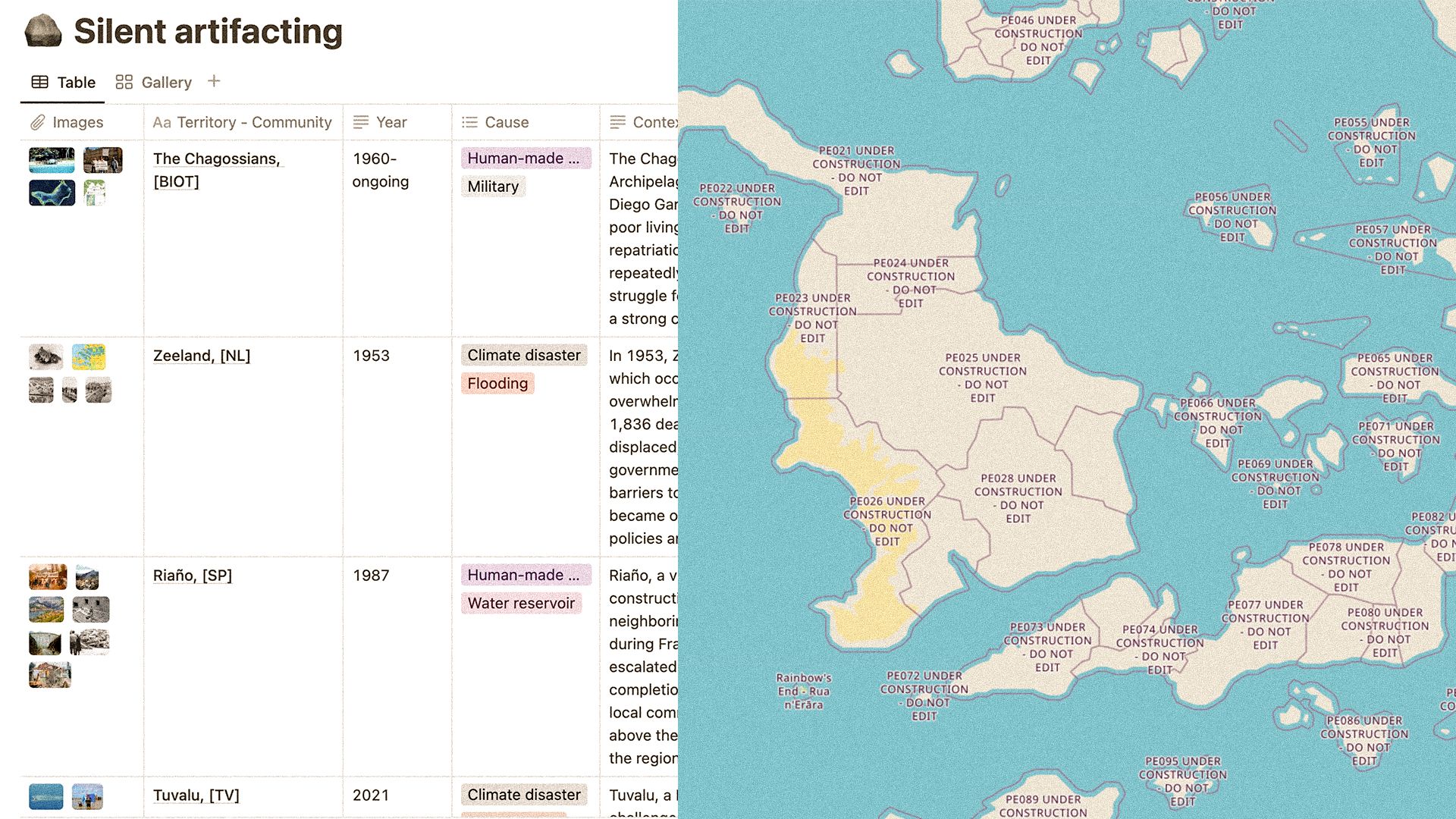

Following input from the talented creatives themselves, a different approach has been

chosen this year: there will be no exhibition. Most do not see the Dutch Design Week as the right place

for them; only one or two are interested in presenting a ‘finished’ design or project at all, and they do not

necessarily wish to do so during the Dutch Design Week. What is more, many of the talented individuals have

used the grant for research and creating opportunities. Therefore, instead of a joint exhibition, the decision

has been made to organise a gathering and to publish profile texts and video portraits on ‘Platform Talent’,

an online database. This will put less emphasis on the work of the previous year and more on the visibility of

the maker and the process they are going through, marking a shift away from concrete or applied results and

towards their personal working methods. Will this form of publicity satisfy the general public’s appetite and

curiosity and will it meet politicians’ desire for results? Has it perhaps become more important to announce

that there is talent and not what that talent is? Or is this a way of avoiding quantification and relieving the

pressure?

Perhaps what unites the talented creatives most is the fact that, although they have been

recognised as ‘high performers’, they are all still searching for sustainable ways of working creatively within

a precarious, competitive ecosystem that is all about seizing opportunities, remaining optimistic and being

permanently available. So far, there is little room for failure or vulnerability, or to discuss the capriciousness

of the creative process. The quest for talent is still a show, a hunt, a competition or battle.

1 https://anderetijden.nl/aflevering/171/Talentenjacht

2 Elizabeth G. Chambers et al. ‘The War for Talent’ in: The

McKinsey Quarterly 3, 1998 pp. 44–57. This study was published

in book form in 2001.

3 Roel Pots, ‘De tijdloze Thorbecke: over niet-oordelen en

voorwaarden scheppen in het Nederlandse cultuurbeleid’ in:

Boekmancahier 13:50, 2001, pp. 462-473, p. 466.

4 Thorbecke was a mid-nineteenth-century Dutch statesman.

5 Bram Ieven, ‘Destructive Construction: Democratization as a

Vanishing Mediator in Current Dutch Art Policy’ in: Kunstlicht,

2016 37:1, p. 11.

6 The Visual Artists’ (Financial Assistance) Scheme was in force

from 1956 to 1986 and the Artists’ Work and Income Act from

2005 to 2012.

7 Ronald Plasterk, ‘Hoofdlijnen Cultuurbeleid Kunst van Leven’,

2007, p. 5. The Dutch politician Ronald Plasterk was Minister of

Education, Culture and Science from 2007 to 2010.

8 Halbe Zijlstra, ‘Meer dan Kwaliteit: Een Nieuwe visie op

cultuurbeleid’, 2012, p. 9. The Dutch politician Halbe Zijlstra was

State Secretary of Education, Culture and Science from 2010

to 2012.

9 Jet Bussemaker is a Dutch politician who was Minister of

Education, Culture and Science from 2012 to 2017.

10 Creative Industries Fund NL, policy plan for 2013/2016.

Text: Rosa te Velde